To suffer in love is the greatest of all joys.[1]

Consider it pure joy, my brothers and sisters, whenever you face trials of many kinds… [2]

What is it about the saints that enables them to suffer so joyfully? Most of us do everything we can to avoid suffering. We dread it, worry endlessly about it, complain to God about it, and even question His goodness because of it. But the saints’ attitude from the time of our Lord until now has always been the same: they rejoice! “Rejoice and be glad,” our Lord exhorts in the Beatitudes.[3] St. Paul, St. James and St. Peter had the same attitude and exhortation.[4] Is this ability to suffer joyfully peculiar only to a select few saints, but otherwise unattainable by the rest of us?

Before we answer this question, let us first consider the nature of our earthly joys. A simple observation will make us realize that, in our fallen world, all our earthly joys are always localized in nature: when we celebrate our children’s birthdays, for example, we do not think about the countless children who never made it out of infancy. When we plan our itinerary for the day, we do not think of the scores of people who are bedbound and cannot go to the bathroom unassisted. When we enjoy a good meal, we do not think of all the starving or malnourished people who are struggling. When we celebrate our country’s independence with parades and fireworks, we do not think of the many countries around the world still battling famine, disease and war. In our fallen world, it is impossible for all creatures to rejoice and celebrate together. This will only be possible in Heaven, where “there will be no more death or mourning or crying or pain.”[5] Happiness in our world is always limited and localized; it can never be a universal phenomenon.

Suffering, on the other hand, is a universal phenomenon. It is a curse that universally affects every creature on earth, from the smallest ants to the greatest historical figures. In his letter to the Romans, St. Paul called suffering the universal “groaning” and “frustration” of all creation.[6] But the saints didn’t stop there: they recognize this groaning as mere “labor pains” that will result in the birth of a new and glorious creation,[7] where happiness will finally be a universal and everlasting phenomenon.

Due to its localized nature, earthly happiness does not usually lead us to contemplate the universal future joy of all creation. Indeed, we often use these little moments of happiness as a short respite from the cares of life, moments where we can forget the whole awfulness of fallen creation. We lose ourselves in a beautiful sunset, in our beloved’s gaze during a stroll, in our children’s laughter when they play in the park. We sigh, wishing that such moments could last forever. They never do, of course, and many of us plan our days chasing after such little moments of happiness—moments where we can forget the drudgery, boredom and banality of our earthly toils. This world, with its self-help books and motivational gurus, encourages us to pursue this kind of lifestyle. And slowly but surely, we get trapped in our little bubbles of anxiety, micro-planning and daily travails,[8] and we lose sight of that heavenly glory that is our future heritage.

The reason Christians can suffer joyfully is because Christ suffers together with us.[9] The Acts of the Christian Martyrs tells us that a few days before St. Felicitas was to be martyred, she gave birth to a baby daughter. During her painful labor, the Roman guards taunted her, saying, “You suffer so much now–what will you do when you are tossed to the beasts? Little did you think of them when you refused to sacrifice [to the Roman gods].” To which the saint replied, “What I am suffering now, I suffer by myself. But then Another will be inside me who will suffer for me, just as I shall be suffering for Him.”[10] Similarly, St. John Paul II reminded us in his apostolic letter Salvifici Doloris[11] (The Salvation of Suffering):

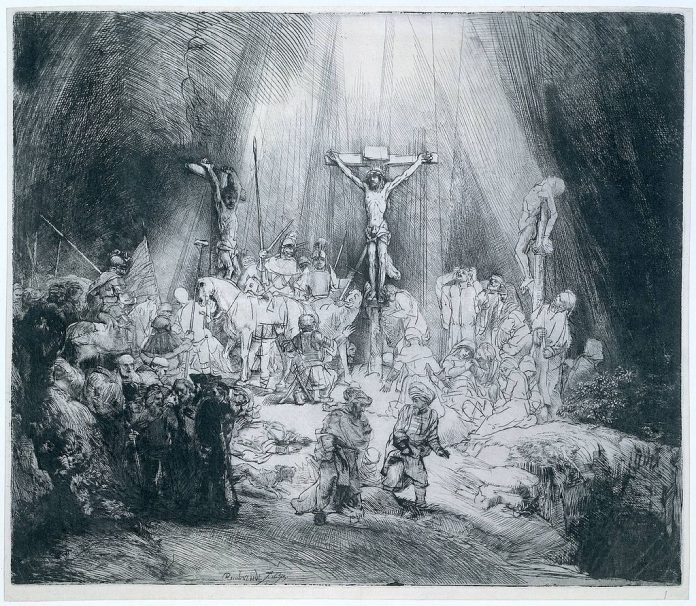

Human suffering has reached its culmination in the Passion of Christ. And at the same time it has entered into a completely new dimension and a new order: it has been linked to love, to that love of which Christ spoke to Nicodemus, to that love which creates good[12]…

In the Cross of Christ not only is the Redemption accomplished through suffering, but also human suffering itself has been redeemed.[13]

Has any of us ever known a pregnant lady who is filled with despair when the labor pangs are upon her? Of course not! On the contrary, she rejoices and is filled with hope, for a new child is about to be born. Similarly, those who suffer together with Christ also taste the sweetness of His embrace, the gentleness of His friendship, and the assurance of His steps that lead to glory. This is how the Psalmist was able to proclaim, “The Lord is my Shepherd, I shall not want.”[14] Indeed, has He himself not promised that His yoke is easy and light, and that we shall find rest for our souls, if only we faithfully take up our cross and entrust ourselves to Him?[15]

Our world today is filled with fake promises, false gods and false gospels,[16] an overload of conflicting information, and little cups of localized happiness that only serve to distract us from the many ills pervading society. When all else fails to distract and divert, many desire death as the ultimate answer to the problem of suffering. What can pierce through this din of mess and empty promises? Tertullian once said that the “blood of Christians is seed”[17]: the seed of a new life, of a new creation. Then as now, the witness of Christian suffering shows the world the Truth of what is to come, of the Redemption that has transformed the meaning of suffering, of the universal joy and glory of Heaven. It shows Christ to the world. This is how the apostles and the saints were able to suffer so joyfully and triumphantly. Let us, then, follow in their footsteps, and thus win many souls for Christ.

So we do not lose heart. Though our outer self is wasting away, our inner self is being renewed day by day. For this light momentary affliction is preparing for us an eternal weight of glory beyond all comparison, as we look not to the things that are seen but to the things that are unseen. For the things that are seen are transient, but the things that are unseen are eternal. (2 Cor 4:16-18)

[1] St. Thérèse de Lisieux, L’Histoire d’une âme (the original French reads: “Souffrir en aimant, c’est le plus pur bonheur!”), Project Gutenberg, https://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/16772.

[2] James 1:2

[3] Mt 5:12

[4] Rm 5:3-5, Jas 1:2-4, 1 Pe 4:12-14

[5] Rev 21:4

[6] Rm 8:20-22

[7] Rm 8:18-24

[8] Cf. Mk 8:18-19; Lk 8:14, 21:34

[9] Cf. Acts 9:5

[10] Herbert Musurillo, The Acts of the Christian Martyrs (Oxford University Press, 1972), as excerpted in PBS Frontline, https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/shows/religion/maps/primary/perpetua.html.

[11] https://w2.vatican.va/content/john-paul-ii/en/apost_letters/1984/documents/hf_jp-ii_apl_11021984_salvifici-doloris.html

[12] Salvifici Doloris, IV.18

[13] Salvifici Doloris, V.19

[14] Ps 23:1

[15] Mt 11:28-30 (cf. Mt 16:24, Mk 8:34)

[16] These, of course, are not new phenomena (cf. 2 Cor 11:4)

[17] Tertullian, Apology, Ch.50, https://www.newadvent.org/fathers/0301.htm.