Saint Anselm (+1109) was bishop of the see of Canterbury, back when it was still Catholic, and remained officially so until the predations of the Tudors, the descendants of Henry VIII. Yet, Anselm had his own struggles with the Kings of his earlier age, William Rufus and Henry I, who wanted to control the Church, her influence and wealth; Anselm suffered persecution and exile, but held steadfast to the rights and privileges that belong to the Mystical Body of Christ in her hierarchical dimension; for he realized full well that the Church cannot carry out her supernatural mission without a natural foundation, free from secular domination (and more on that soon in an article on the troubling situation in China…)

Anselm is also credited with helping to found what we now know as the ‘university’. His cathedral school, with young men gathered around scholarly clerics learning the ‘liberal arts’, those subjects that make a man ‘free’ from the slavery of ignorance, an ignorance in which we are now wallowing, in our own modern-dark ages.

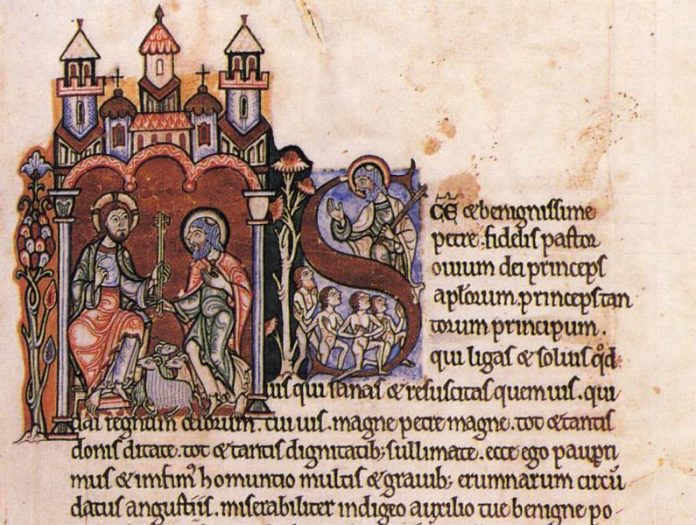

Before his episcopacy, Anselm’s Benedictine abbey at Bec, which he joined as a young man, and soon afterward appointed Abbot, was considered the foremost seat of learning in Europe. Through his writings and teaching, Anselm is hailed as the founder of Scholasticism, that whole invaluable theological-philosophical method, which brings faith and reason together into a perfect harmony and synthesis, and which Saint Thomas Aquinas would bring to perfection in the century after Anselm’s death.

Like the future Dominican, Anselm was an implacable foe of the heresy of nominalism, the theory that nothing could really be known, and that all knowledge was really just ‘names’ we applied to things, ever-shifting, which, in its moral application, the future Pope Benedict XVI would term the ‘dictatorship of relativism’.

Not so: Pope John Paul II’s 1998 encyclical Fides et Ratio is one long exhortation on the bold and courageous capacity of the human mind to know, to grasp truth, the adequatio rei et intellectus, the ‘conformity of the mind to reality’, and to live by that truth, the only thing that will truly ‘set us free’.

In that same encyclical, John Paul described Anselm as ‘one of the most fruitful and important minds in human history’. His precise yet transcendent treatises on God, Christ, Our Lady, the Fall, Incarnation, the ontological proof, faith seeking understanding and a vast array of other subjects make his writings a solid part of the Church’s tradition, and he was declared one of the (now) 36 Doctors of the Church by Clement XI in 1670.

Anselm saw the Revelation of God, the study of which we call ‘theology’, as extending and perfecting the range of human reason, which otherwise remains limited, barren, weak, pusillanimous, eventually turning bizarre and even evil without the guidance of the truth that only God’s revelation, through His Christ and His Church, can provide.

Popes John Paul and Benedict have warned us that as we lose faith (or adopt erroneous faiths), we also lose reason, our grip on reality, and a kind of global and even infectious insanity ensues, as any glance at daily newspaper headlines will clearly evince.

Unless we return to the fullness of truth, which means that harmony between faith and reason, theology and philosophy, immersed and formed in the Church’s whole tradition of the liberal arts, we are quite literally doomed, at least doomed to ignorance and all that entails.

If one need examples, ponder our loss of even basic truths, such as what human life means, its inherent dignity, the nature of married and sexual love, what it means to be man and woman, to say nothing of socioeconomic principles, the purpose of private property, human initiative, why marijuana is bad for you, and all that it means to be ‘educated’.

As the prophet Hosea warned, ‘my people are destroyed for lack of knowledge’.

And he meant that quite literally, as it turns out.

On that note, it seems now that another venerable personage, Dr. Hans Asperger, has been a posteriori vilified, this time as a sympathizer with the Nazis; accusations are made that he sent ‘unfit’ children to Am Spiegelgrund, the infamous children’s ‘hospital’ where 789 sickly children were put to death under the National Socialist’s ‘euthanasia’ program, also known as Aktion T, which does has a Nazi ring to it, as a prelude to the much more vast ‘final solution’.

Before we throw stones at Asperger or any of the more verified collaborators, we should be aware that we ourselves are but a stone’s throw away from the same thing happening here in Canada. The recent M.A.I.D legislation permitting ‘euthanasia’ for now sets limits for ‘assisted suicide’ to adults, but the move is afoot to lower the age of consent, if consent itself even remains a factor. After all, why discriminate? Cannot those under that magical age of 18, even those ‘unaware’, feel ‘unbearable’ pain, and cannot they too be deemed, what was that Darwinian term, ‘unfit’ to live?

How long before medical assistance in dying becomes more about enforced assistance, than choosing to die?

It seems the #MeToo movement has hit the estimable Nobel Prize committee in Sweden, with claims of sexual harassment against the husband of the Secretary (female, of course; one must specify nowadays) who, against all tradition, has resigned (which is technically against the rules). Details are sketchy, but it seems ‘unwanted advances’ were to blame.

No one is safe, it seems. I have always wondered about these committees that award baubles so esteemed by the world. As Cardinal Newman once wrote, the thing most people crave, deep down, is what he termed ‘newspaper fame’, the desire to be known, remembered and feted by the world. And there are few better ways than a Nobel Prize. And what many people crave often gets corrupted, due to original sin, envy, and a disordered sense of ambition.

In a more lethal variety of show trials and guilt-by-association, a podcast I listened to the other day described the criminal trials taking place in Iraq for former IS collaborators (or ISIS, or Daesh, or whatever is now the acronym de jour). One might recall, although it seems ancient history now in our harried era, but a scant few years ago, the ‘Islamic State’ ran more than half the country, murdering, throat-cutting, enslaving, raping, pillaging and crucifying at will. Now, as these criminals are on the run, comeuppance and revenge is upon them. He who lives by the sword…

These trials apparently last an average of ten minutes, with about two minutes offered for a ‘defence’, with hazy witnesses and recollections, after which either a pardon is given, or a death sentence handed down, and summarily carried out. An eye for an eye, and a tooth for a tooth? One farmer was executed for using his truck to ferry water to IS soldiers, something he claimed he was forced to do at gunpoint. Too bad.

These trials have also not spared women, mothers, leaving children orphaned and at the mercy of a rather unstable state bureaucracy.

One is reminded of the show trials of the French Revolution, with ‘enemies of the state’ brought to the guillotine after a few minutes of questioning. One minute your’e being harangued for not expressing the virtues of un citoyen, and the next, your head is rolling along the cobblestones of the Place de la Revolution.

Sure, justice must be served in a harsh and brutal environment, and but it need hardly be said dishing it out this way will not solve things in Iraq and throughout the rest of the Middle East, descending into chaos; rather, such will only breed more resentment, anger and revenge. Can Islam really be ‘purified’ of its more radical elements, whether here, in terms of persons, or, in the broader sphere, its ideology? Or are such trials more evidence of the inherently ‘radical’ nature of the austere Arabic desert religion, whose 7th century origins are themselves rather radical, and evince many troubling elements more in common with the methods of IS than we would like to admit? Who’s to say what’s good and bad in Islam?

Well, my answer is Christ and His Church. To return to Anselm, at the end of the day, and at least the end of our lives, we must choose either Christ, or something that is not Christ, all that is, as Saint John described, the spirit of anti-Christ. For just as Christ cannot be divided, neither can His truth; how we have lived by that truth, we all will be judged at the end of this earthly sojourn.

On that hopeful note, Saint Anselm of Bec and Canterbury, ora pro nobis!