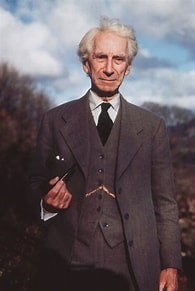

Everyone wants to know what happiness is and how to get it.(*) The philosopher Bertrand Russell (1872-1970) was no exception. He first published his little book The Conquest of Happiness in 1930 and it has sold fairly well ever since. I read it myself when I was in my early thirties, and was much impressed with Russell’s valiant attempt to achieve for irreligious humanists a handbook of spirituality comparable to anything Christianity had produced. Much impressed, that is, except except for Russell having left God entirely out of every type of search for happiness. Despite his reputation for genius, so far as his views on spirituality without God were concerned, Russell even in old age, when wisdom is supposed to arrive, was sadly among the most shallow of modern thinkers.

Some of his book’s chapter titles give an idea of the range of its contents: “What Makes People Unhappy?” “Competition.” “Boredom and Excitement.” “Fatigue.” “Envy.” “Persecution Mania.” “Fear of Public Opinion.” “Zest.” “Affection.” “The Family.” “Work.” “Impersonal Interests.” “Effort and Resignation.” “The Happy Man.” As Russell indicates in the preface, this book is not written for highbrow intellectuals, but for the ordinary person who is encountering and struggling with the ordinary obstacles to finding a measure of happiness. I think it is only fair to concede that to some degree Russell achieves his goal. I remember well the sense of peace and calm that overcame me while reading his book at a slow and deliberate pace.

Yet something in the book was missing. It was perhaps the same thing I found absent in many of the Protestant churches I visited when I was on my journey back home to the Catholic Church. It was the sense that the persistent questions at the inner core of my being were not being answered by what I saw and heard in these churches. Let me briefly summarize this point by addressing the chapter in Russell’s book titled “The Sense of Sin.”

I, and I suspect most people, have a profound sense of disappointment with my tendency to behave in ways that do not show me to myself as my best self. Why is this? Why should I have such high expectations of myself? Is that unreasonable? “Be ye perfect, even as your heavenly Father is perfect.” (Matthew 5:48) If that is what God is calling me to be, as perfect as possible, it is then inevitable that I should be disappointed with my sins. I should acknowledge my sins by examining my conscience. I should be humiliated by my sins, confess them, and do penance for them rather than exult in them or shrug them off as inconsequential and to be ignored. How else can I beat a path to my more perfect self?

This is not Russell’s take on sin and happiness. Russell believes that most sin, and the guilt that follows sin, is inherited from the morality we were taught in our childhood, especially the morality our mothers taught us. When we grow up, we never forget that morality, but we learn to live with the sense of guilt it continues to exert on us. In other words, Russell argues, the guilt of sin is something infantile that we ought to outgrow if we want to be happy. Psychoanalysts, Russell says, have learned that this is so, and he believes them. Much of Russell’s attention to sin is centered on sexual sin. Once we overcome the puritanical prohibitions of our ancestors, he thinks, we will be guilt free and happy. But Russell’s own married life was a questionable conquest of happiness if we judge by a procession of four wives throughout his life.

We see too many lives made unhappy, rather than happy, as a consequence of the sexual revolution that Russell is famous for helping to ignite. The rise of adultery, incest, pornography, prostitution, sodomy, pedophilia, and every other enslavement to our sexual passions convinces me that Russell, for all his eloquence with the pen, entirely miscalculated. We are happier when we hold our sexual passions in check or in moderation. The guilt and misery we experience for our sexual sins is natural, well deserved, and often therapeutic, especially when we realize in unbridled sexuality a tendency to excesses that lead to neuroses or psychoses or a whole panoply of serious diseases. The refusal to believe in sin is not just sinful, but also self-destructive.

Adam and Eve, like Russell, bowed to the first temptation of the Serpent, who offered to console them and encourage them in the belief that they could be as gods themselves by eating the forbidden fruit. In other words, there would be no higher power than themselves, which is the founding principle of all atheism.

The defect in Russell’s spiritual therapy is that it excludes any sense of the presence of God in our lives. Absent God, we are without the grace that God bestows on all who turn to him for comfort. There is nothing in Russell’s book that gives an atheist spiritual comfort when he lays dying.

Voltaire said (and I believe Francis Bacon said it before him) that atheism is a shallow philosophy. It does not think things through, and that is because it usually begins early in life before it has had time to think things through. This is precisely what happened to Russell who, at the age of eighteen, examined all the proofs for the existence of God and found them insufficient to convince. He took, for example the “first-cause” proof and asked why there had to be a First Cause of everything in all creation. Why could the universe just always have existed? That would be just as rational as the claim that God always existed and was never created. Now this argument Russell related in 1927 in his essay “Why I Am Not a Christian.” But the science of the Big Bang, with delicious irony, began to be revealed in that very same year of 1927 by the mathematician-priest George Lemaitre. The theory, later proven by astronomical observations, argued that the universe was indeed created; therefore posing the question: Who Created it? Wasn’t there a First Cause?

At the same time, Russell also asserted that every religion is a disease born of fear, and that this fear is the parent of cruelty. He said this in spite of the Christian religion, which is clearly the parent of both hope and fear: hope that our final destiny is to know God up close and personal as the result of a life well lived; fear that we will not. The notion that atheism is not the true parent of cruelty must be countered by the recognition that so many of the cruelties of the modern world stem from atheistic communist governments as proven in the history of Russia, China, and North Korea and others even to this day. Russell, who died in 1970, certainly lived long enough to see that the cruelties of atheistic governments in his century far exceeded any pseudo-religious scandals of the past. Moreover, Katherine Tate, his daughter and a Christian convert, observed her father always harped on the failures of religious institutions and could not bring himself to admit the good they have accomplished.

The atheist is content to slam the door on the immortality of his soul with a simple and resounding “No!” But sooner or later some atheists are drawn to deeper thinking. The atheist philosopher Jean Paul Sartre learned in the last year of his life to rethink the worth of his atheism. So did the atheist philosopher Antony Flew. Christopher Hitchens, author of the book God Is Not Great … How Religion Spoils Everything, shortly before his death welcomed the prayers of his Christian friends. Such conversions happen because no atheist can with absolute conviction prove there is no life other than this one. But every atheist, if he will let himself, can believe with absolute hope that another life is worth believing in. Russell dismissed the idea that deathbed conversions of atheists are common. But in a striking display of sloppy logic for so famous a logician, how could he claim this except as an unwarranted guess?

The fact that we must all die resonates with varying degrees of tension through every day of our lives. The chapter concerning happiness that is not in Russell’s book might be the one that, if it had been written, might concern the desperate plight of those who, as they lay dying, need more consolation and hope than Russell’s atheism could possibly inspire. On the other hand, it is surely not common sense to argue that any true Christian on his deathbed will turn to atheism for even a crumb of hope and consolation.

Could Russell not have had seriously second thoughts as he lay dying?

Prayer for Atheists

Father, You said we should ask and we would receive.

Today many in the world have hardened their hearts

against You. It is for them that we ask,

as they will not plead for themselves.

Soften their hearts.

Some once believed in You and have lost their way.

They have become sad or bitter for a hardship

or failure in life. In childhood they may

have lost a parent by death or abandonment.

Soften their hearts.

They may have known the death of a child,

or the loss of a partner. Joy has gone out

of their lives and they have turned against You.

Help them to feel Your loving spirit once again.

Soften their hearts.

On the cross You joined them long ago

in their pain. Help them to sense, even though

they have turned from You, that You are

a haunting presence … You will not go away.

Soften their hearts.

Let each one of them one day be walking

along a beach, or reading a book,

or entering a room … and hear a voice,

however distant, calling from within …

“Come, follow me.”

(* As an editorial addendum, I read recently that the most popular course at Harvard is one on happiness; but, like Russell’s book, I do wonder how happy it makes those many thousands who enroll).