“A sentimentalist is one who desires to have the luxury of an emotion without paying for it.” Oscar Wilde

Stuffed animals, flickering candles, cello-wrapped flowers, unfocussed anguish and tears. What’s all this really about?

I’m referring to that contemporary and now commonplace phenomenon triggered by yet another violent outrage in yet another unsuspecting community where entire families, neighbourhoods and even countries are left in shock.

Picture the scene, which you’ve seen so many times before. A mass shooting, somewhere – or some other atrocity – in a once peaceful neighbourhood. Police, ambulances and reporters appear within minutes. Then, within hours, a ‘holy’ spot close to the crime scene is designated by some nameless person. And magically, candles, flowers and teddy bears start appearing like mushrooms. In grief, in shock, in memory and in tribute to one or more tragic victims. Items usually left by persons unknown to the victim(s).

Such public outpourings are not new. Indeed, this phenomenon has become as predictable as a wallpaper pattern repeated endlessly, identically, over and over and usually with a vigil held over a series of evenings in homage to the victim(s).

Call me unfeeling, but all this says so much about our culture and our spiritual condition these days and how vapid it’s all become since it was first manifest twenty-two years ago with the shocking death of Diana, Princess of Wales, an event which triggered a response as shocking as the event itself.

Diana, 1997

Most readers still remember how Diana’s death in Paris in August 1997 was followed by a week such as the world had never seen before. Such was the intense grief and public hysteria over someone that millions of mourners didn’t even know – except vicariously. And anyone who witnessed it will never forget it.

I was there in London, reporting, yet deeply disturbed by the unreality of it all. Nor could I shrug off the persistent creepiness, particularly on the evening before her funeral when I walked through Kensington Gardens to witness candles everywhere, strange mini-shrines further than eyes could see, hushed conversations, and the massive bank of flowers piled chest-high outside the main gates. Within minutes, I wanted to flee.

All this came at the end of a week of rising outcry from the public and the media taking offense at what they deemed a lack of emotion by the Queen for not falling to pieces before a bank of cameras. But that’s what was wanted. Not a monarch in control of herself overseeing her country. No. What was wanted was a public performance by a sobbing mother-in-law demonstrably out of control.

But not everyone sympathized with this demand, including author and prison psychiatrist Dr. Theodore Dalrymple. He contended that “the tabloid newspapers carried out what can only be called a campaign of bullying against the sovereign” and that the sentimentality shown by both the media and the public “was inherently dishonest in a way that parallels the dishonesty that lies behind much sentimentality itself.”

Even so, the dramatic international response to the death of Diana marked the beginning of a new form of public behaviour. It provided a flash, a highly illuminating snapshot if you will, of people’s souls that year. Suddenly traumatized by a violent unexpected death, it should have been instantly apparent how much influence the media and its constant fog of unreality had been having on the madding crowds whose souls had been absorbing its hedonistic message for decades. And now here the crowds were, in plain view – ripped out of their somnambulism and their Hollywood fantasies and confronted by a waking nightmare which involved a very unhappy ending, death and its inescapable reality.

Talk about a wake up call!

Lessons unlearned

But no. Few woke up and life soon returned to ‘normal’. Still, what the world witnessed that week was a flash, an illuminating snapshot if you will, into the unreality, superficiality and sustained immaturity of its media-maddened population. And that hasn’t changed. More than two decades later, this once hidden penchant for intense emotionalism has become full blown. As has its predictability whenever another ghastly event occurs, such as a school shooting, an act of bloody terrorism or another particularly hideous incident of family violence. The result? Candles, flowers, teddybears, group hugs and tearful, often incoherent, statements to ubiquitous microphones indicating yet again that feelings and emotions trump all, at the expense of reason.

And reason? Well, reason is now in almost total retreat, so much so that a failure to produce tears is often seen as evidence of heartlessness, even cruelty. Particularly on TV where one’s camera-ready ability to weep on cue is proof of ‘caring’, of feeling the pain of others and therefore possessing moral superiority. I cry, therefore I’m better than you, could be the mantra: I’m a victim of a horrible childhood, therefore I’m as much a victim as those I may have victimized.

As for its opposite – emotional restraint, self-discipline and the gracious acceptance of pain as a sign of adulthood and of dignity? Fuggedaboutit!

A bit harsh, you’re thinking? Perhaps, but where did all this start?

A History of Sentimentalism

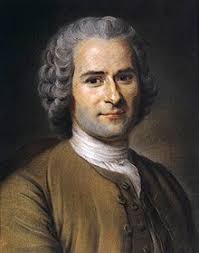

History blames Jean-Jacques Rousseau, the 18th century French philosopher whose elevation of feeling over reason made him a prophet of the ultramodern era that would soon eclipse the Age of Reason and give rise to the Age of Victimhood, which is where we are today.

Also blamed is the Age of Romanticism which led to a change in man’s conception of himself, of sin and personal responsibility. Interesting too that the Romantic Revolution also ushered in the era of massacre for ideological reasons, but that’s another story.

“The Christian view, that man was born imperfect but could and should strive towards perfection, was first challenged and then replaced by the Romantic view that mankind was born naturally good but was corrupted into badness by living in a bad society,” writes Dalrymple in his book, Spoilt Rotten. “Thus the exhibition of vice became evidence of having been treated badly. What had been deemed a moral defect became victimhood.”

And the best way to correct that, Dalrymple notes, was social engineering on a huge scale, which meant socialism and its attendant errors: “The Christian view is much less sentimental than the secularist. The secularist sees victims everywhere, hordes of suffering people who need rescue from injustice. In these circumstances, it has become advantageous to claim victimhood for oneself – psychologically and sometimes financially – because to be a victim is to be a beneficiary of injustice.”

By contrast, he continues, the Christian view acknowledges that folly and wickedness are inescapably part of the human condition. These vary in degree between individuals, but they inhere in all of us. Which is why it’s possible for someone who believes in Original Sin to be clear-sighted and compassionate at the same time, but very difficult for someone who believes in mankind’s natural goodness, who forgives all because he claims to understand all, and then becomes indifferent and unfeeling.

And so it follows that for the sentimentalist, there is no such thing as a criminal, only an environment that has let him down.

Thus personal responsibility, conscience and sin were jettisoned, which is exactly what some philosophers of the Enlightenment wanted.

The Rise of Secularism

Just as they wanted Christian beliefs to be publicly rejected to make way for Christianity’s biggest opponent – secularism – which, in turn, would open the door to Marxism and Freudian pan-sexualism allowing the achievement of the ultimate goal – the denial of God in the public square and the subversion of all of Christendom, its institutions and its population with the singular purpose of destroying it outright.

And in its place would come an aggressive sentimentality seeking to dominate the world and which, as English philosopher Roger Scruton points out, is essentially totalitarian because, as with totalitarian governments, it seeks out opposition and carefully extinguishes it in all the places where opposition might form.

“Sentimentality’s goal is to ‘solve’ our social problems by imposing burdens on responsible citizens, and lifting burdens from the ‘victims’ who have a ‘right’ to state support,” Scruton writes. But as this occurs, something curious happens: “As the state takes charge of our needs, and relieves people of the burdens that should rightly be theirs – the burdens that come from charity and neighborliness – serious feeling retreats.” And those old social problems which might have been relieved by private charity are replaced with new and intransigent problems fostered by the State through its liberal ideologies. Problems such as mass illegitimacy, the decline of birthrates, the emergence of the gang culture among fatherless youth along with so many other destructive ideas promoting chaos and despair.

Central to all this is the fundamental denial of the fallen-ness of human nature itself which has been replaced by the lie that there are only fortunate and unfortunate circumstances into which human beings are born or subjected. Which the State can correct insofar as individuals can be persuaded to abdicate personal responsibility and embrace victimhood which, in turn, leads directly to their dependency on whatever agency will take responsibility for them in exchange for protection, and their temporal and even emotional needs. This is also a condition that, not accidentally, opens itself to totalitarian control and an increasingly infantile population.

But what does this condition – and all its mawkish and comfort-seeking pathology – signify really?

Spiritual neglect and starvation

What this signifies is spiritual starvation, evidenced by the abject spiritual ignorance found in so many young people today who receive no religious education worthy of their intelligence and of their deep need as children – not of nature and superficial paganistic notions – but of God. Therefore, it shouldn’t surprise anyone that so many of them are famished, and that, in the absence of nutritious spiritual food, they latch onto the equivalent of spiritual junk rather than the prayer, scripture and hard teaching their minds and souls crave.

There has also been an almost total failure to teach them what Catholicism has always regarded as essential knowledge for all human beings about the final stages of the soul in this life and the afterlife. These are known as The Four Last Things – Death, Judgment, Heaven and Hell – which St. Philip Neri advised all religious beginners to meditate upon, thereby placing themselves as God’s children into proper relationship with Him, their Creator, while also beginning to prepare themselves for their inevitable physical death and their life in the world to come.

It is this fundamental knowledge and training that is missing today, and the immortal soul of every person senses it and seeks it. And, if found, it can provide the basis of obtaining the ultimate goal of every human life – a happy and holy death which is the threshold to Heaven and God Himself.

Yet without such fundamental knowledge and preparation, how are the unschooled young and old alike supposed to react to the traumas of life, beginning with the very fact of death itself, with which every human being is confronted?

When confronted by a traumatic and sometimes inexplicable event, how can a makeshift shrine and paganistic vigils answer that need? Yet aren’t all those candles and teddy bears and decaying flowers what this is really about?

Memento Mori

Isn’t this really all about Memento Mori, objects that remind us that we will die? But there’s a twist here. Aren’t those soft and soothing reminders of childhood really about the frightened soul seeking comfort and relief from their natural fear of death – for which they’ve been given little or no preparation whatsoever? No wonder so many become obsessed with the macabre – a theme which dominates so much of cinema and TV today, such as The Walking Dead.

The greatest irony of all this, though, may be that by erecting all those shrines that mark today’s cult of sentimentality and victimhood, these very victims denying the reality of sin may also be setting themselves up for victimization by the very demons that, in the words of Saint Peter, and repeated at the dawn of the twentieth century by Pope Leo XIII, wander through the world seeking the ruin of souls.

But that’s been the game since the very beginning, has it not? From the time Lucifer and his angels were thrust out of heaven and hurled into hell, they’ve spent the past millennia seeking to drag as many of the Lord God’s beloved children as can be tempted into joining them in hell for eternity.

And that’s the truth that every human soul senses, regardless of what they are told. Yet once he denies God and fails to seek His Holy Face, he is left to their own devices which, barring divine intervention, results in turning to themselves, which soon turns to self-obsession and then succumbing to Satan’s ultimate deceit dating back to Eden: “Ye shall be like gods.”

Which, of course, ye shall not! As all of history proves.