John of Capistrano (+1456) lived a life very much in the ‘world’ at first, studying law, and becoming involved with the political machinations of the fractious fifteenth century. He was appointed as ambassador from Perugia to the quarrelsome family of the Maletestas – which, ironically, means ‘evil heads’ – to broker peace, a mission which landed him in prison.

Like his forebear, Saint Francis, this enforced time alone with his own thoughts allowed him to reflect upon his life – a salutary practice later advocated by Blaise Pascal, who claimed that the world’s problems could be solved by people just spending half an hour in alone in a quiet room (so unplug that i-phone!). John’s newly-awakened conscience opened a window to the ‘still, small voice’ of the grace of God, prompting him, suaviter et fortiter, to seek out the austerity of the Franciscan Order, which he entered on the founder’s feast day, October 4th, 1416. The zeal he had shown in lay life was doubled in his religious path, and Friar John soon became one the most fervent of friars, with his deep prayer life, rigorous asceticism, and his fiery sermons attracting such multitudes that no church could hold them. Recognizing his ability, or the grace of God working through him, the Church sent Friar John on numerous diplomatic missions, in which he was unbending in his refusal to compromise the truths of the Faith.

His life was controversial: There are claims his sermons tended, shall we say, to what we now call the ‘anti-Semitic’ (admittedly, an ambiguous term), as his condemnation of the Jewish religion went beyond what some might consider prudent boundaries; but, at least, a religious syncretic Father John was not, and a fervent supporter of the Inquisition. Also controversially, he was gung-ho in gathering together and leading troops into battle against the Ottoman Turks. Like his near contemporary Joan of Arc (+1431), Friar John did not fight, nor was he armed; his mission was to exhort the troops, and provide what spiritual ministrations were required.

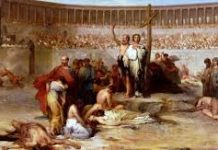

Just so, he helped lift the siege of Belgrade in 1456, as the Muslim hordes, fresh from their conquering of Constantinople in 1453, attempted the conquest of Europe. The reader may listen to this talk on the incredible story of this fateful battle – with a group of inexperienced Christian men, armed primarily with the grace of God and the rightness of their cause, against a war-hardened array of Islamic warriors, trusting in the Holy Name of Jesus, which was their battle cry.

Father John was insistent that his fellow priests also not fight in any way, nor even offer material assistance, such as handing over weapons – rather, their arms and armour were to be purely spiritual, praying, hearing confessions, interceding. Few could keep up with the septuagenarian cleric, as he ran to and fro, scarcely sleeping, until, by a miracle, the Turks were routed, fleeing in disgrace.

The Holy Father ordered that the final day of victory – August 6th – be the day chosen to celebrate the Transfiguration, in honour of the miracle.

It was a few months after the strain of this endeavour, when he was already 76, that he caught the bubonic plague raging through the camp, and died on October 23rd of that year, 1456. It’s good to know that saints can be holy, yet still be ‘men of their age’, with all the limitations thereof. We could use a few more men who refuse to compromise or please, who don’t much care about being ‘liked’, and are willing to stand up for, even fight if need be, for what they believe. There is hope, then, for us all, who are mired in the maelstrom of our own fractious and unsettled time, that even if we don’t do the perfect thing, God provides for what is lacking, so long as our hearts and minds are founded in Him.

Saint John of Capistrano, ora pro nobis!