(A re-posting of my reflections, nearly two years ago now, of my pilgrimage to Canterbury, in light of today’s memorial to one of her greatest Archbishops, indeed one of the most outstanding bishops of any age, Anselm)

I hurtle in one of France’s TGV’s towards Rome, with ancient, stone-built French villages blurring by, nestled quite naturally in the breathtaking beauty of the Alps; there is a seemingly endless lake, whose name was Bourget, as a fellow passenger replied when I asked its name…but more on France later. For now, my thoughts turn back to Canterbury, the last of my pilgrimages in England, whence I departed this morning.

Fittingly so, for ‘Canterbury’ in many ways defines English Catholicism. Made famous by Chaucer and his classic tale merry pilgrims, it was the Catholic Church that made Canterbury what it was.

For the pilgrims in Chaucer’s tale were going not to see the sights of a mediaeval village, but to see the site of a martyr, Saint Thomas a Becket (+1170), lawyer, king’s confidante, bishop and martyr, whose tomb in the cathedral became one of the greatest shrines of the Middle Ages.

Thomas stepped into the shoes of the first bishop of Canterbury, Augustine (+604, pronounced in England, ‘Austin’, but not always, as I discovered). He, like the ‘other’ Augustine, from Africa, was a Roman citizen. Neither would have considered himself ‘African’ or ‘Italian’, but Roman, for there was but one Empire, one civilization. As Hilaire Belloc points out, the whole notion of ‘nations’ came much later in history. Outside of the Empire, were the un-civilized, the barbaric.

So too, there was one ‘Church’ to which they belonged, the Catholic, outside of which there was paganism, the yet-to-be redeemed. There were no romantic notions, as the later, fervid atheistic imagination of Rousseau was to conjure up, of the ‘noble savage’.

Also, there were no (and still really are not) ‘denominations’ of Christians, and, as Newman discovered in his own historical research, Anglicanism did not come to be until after Henry VIII, its progenitor; as Newman put it, to delve into history is to cease to be a Protestant. But more of that in a moment.

Augustine, that is, of Canterbury (we now know him by the name of his See), seems to have originally belonged to the Benedictine monastery on the Coelian Hill in Rome, founded by Pope Gregory, the first pontiff of that name, later to be called ‘Great’, for a whole host of reasons.

One of those reasons was Gregory’s missionary zeal, for it was he who commissioned Augustine to convert Britain. Upon witnessing some ‘Angles’ being sold as slaves in a market place (who would give their name to ‘England’), Gregory was moved to do something, prompting him, in a play on words, to turn these ‘Angles’ into Angels, and not just them, but all the other tribes they would discover, the Saxons, Celts, Picts, all of those ‘outside the frontier’, for by the time of Gregory, the empire was not only civilized, but Catholic.

The Romans had spread abroad, through might and main, the material benefits of their culture, the whole codification of laws, military discipline and training, building techniques, plumbing and clean water, and sewage, literature, two refined and advanced languages (Latin and Greek) allowing for the advancement of thought and philosophy, as well as, while we’re at it, heated flooring and fine red wine.

They made a foothold in Britain, but the legionaries departed in 410, not to return, and the island had sunk to some degree back into barbarism. Irish missionaries had made some advance spiritually in the north of the island (see my reflections on Catholic Glasgow), but the south was largely unconverted.

So Gregory and Augustine, as both Roman and Catholic, wanted to offer the pagans, as they themselves had received, all the supernatural goodness that would perfect what natural foundation they had: the Church’s creed, her moral code, and a structured prayer and liturgical life, not least the Holy Eucharist (which is ultimately why all the cathedrals were built, and which holds everything else together), all of which produced a human flourishing, in this life but, more importantly, in the next.

Again, to Belloc, who declared quite emphatically that is was the Faith that built Europe.

Augustine and his merry band of stalwart missionaries went forth in year 597, landing on the isle of Thanet, where they were at first discouraged by the resistance of the pagan Angles; Augustine even returned to Rome, asking the Pope to be relieved. But the Pope, good father that he was, encouraged Augustine to persevere, and, good son that he was, the monk returned with his band of hearty followers.

I was intrigued to learn that what struck the people of Canterbury (about 18 miles from the coast, then called by its original Latin name of Durovernum) was the solemn procession of the monks into the town, these hardy, masculine, celibate men, completely dedicated to God, bearing the Cross and intoning in unison one of the ‘rogation’ litanies, in that beautiful and mystical Gregorian chant, named after the same Pope.

What a sight it must have been, and I don’t think the same impression would have been made with a band of lutes (that is, guitars) and drums, a sloppy procession, and a round of shaking hands, as one sees all too often in what passes for liturgy today, alas. Music, and by that I mean proper devotional music, has always been the greatest artistic treasure of the church, and a most fitting means of evangelization.

His queen already a Catholic, King Ethelbert was soon convinced by the teaching and example of the monks, and accepted baptism. Thousands of his people soon followed, and England, in a word, became Christian in the full ‘Catholic’, or universal, sense of that word.

The king gave them a grant of land outside the town, and the monks, as is their wont, got to building, tilling and cultivating; the impressive monastery ruins that stand to this day are a silent, but powerfully evocative, testament to what they accomplished. It was the monks who constructed, in more ways than physically, what was and is known as ‘Canterbury’.

The imposing cathedral, which dwarfs in size even modern skyscrapers, where Becket would be martyred near a side altar six centuries later, was constructed in the 12th century, itself a witness to the deep faith that had been instilled in the once-pagan ‘Angles’.

And so Canterbury remained, Catholic to the core, until the tragic years of 1535-40, when the Faith was all-but-obliterated from Britain; the fates of Buckfast and Walsingham also befell the Augustinian Abbey, handed over to the King.

But the dissolution was prefigured by the murder of Becket four centuries earlier; he died for a principle, that canon law, in his time, forbade clerics to be tried in a secular court, something that stuck in the craw of the then-king, Henry II. We all know the story: in a fit of desperate fury in what he perceived as the bishop’s intransigence, the king asked aloud who would rid him of this ‘meddlesome priest’. And so the four knights dispateched the bishop, described immortally in T.S. Eliot’s poem.

What distinguished Henry II from the eighth of that name, was that the former, like Saint Peter, repented, making his own ‘pilgrimage’ to what would soon be Becket’s shrine, while having himself publicly flogged by a monk, for his part in the saint’s murder.

Henry VIII also resisted a theological principle, that only the Pope (in his day) could grant annulments. When the Pope refused Henry’s request to declare his marrage to Catherine of Aragon invalid, the king had the then-bishop of Canterbury, the obsequious Thomas Cranmer (who would later perish in flames under Henry’s Catholic daughter Mary) illiclty grant him one.

Unlike Henry II, Henry VIII most emphatically did not repent, but stuck to it, declaring himself ‘Head of the Church in England’, thereby founding a whole new religion (even though he considered himself a Catholic to his death).

And so what began as an abstruse point about the validity of Henry’s marriage, soon escalated into Henry making himself a secular Pope in England. In short order, he took for himself not only all the spiritual authority, but also the temporal, arrogating into the royal treasury all the land, wealth and privileges of the Church, built up over centuries, so there might be no resistance left. Those who did, who refused the King’s sacrilegious ‘Oath of Supremacy’ were summarily tried in compliant courts, and hung, drawn and quartered (or beheaded, at the King’s ‘mercy’).

Hence, Becket’s murder at Canterbury by the order of Henry II adumbrated the far more widespread murder, by order of the Eighth Henry.

By the time Henry and his henchmen under Cromwell were done, that is, by 1540, there were no monks, no nuns, no monasteries or convents, left in England.

Such is the force of principle, which holds everything together. Once we deny principle, in principle, the whole edifice falls apart. What began as the ‘King’s marital question’ ended up in the ruin of the Church in England.

We might assume that Henry at first knew not the full implications of his theological dogma, that the State should govern the Church, and that is a large part of the tragedy. There are stories of his deathbed repentance, but one wonders. The King supposedly said at one point while dying, ‘All is lost, kingdom, soul…monks, monks, monks!’.

The shrine of Becket? It was destroyed by Henry’s men along with the Abbey in 1538, the relics of the still-meddlesome-saint scattered and lost to the four winds. There is now a modest altar and a plaque (commemorating Pope John Paul II’s visit in 1982) on the spot where he died in the cathedral, since Henry’s time turned to Anglican use, sort of ironic now the cathedral is in the hands of those whose Erastian theological principles Becket would most vehemently deny.

The Abbey? It was converted into a royal residence for a time, first, for Henry’s fourth ‘wife’, Anne of Cleves, whose plain appearance put the King off (the marriage was never consummated, and duly and quickly annulled). Ironically, this was the beginning of the end for Cromwell, who had arranged the nuptials. The by-then ungoverned fury of the King turned against his ever-loyal minister, and Cromwell was soon beheaeded.

The Abbey? It was converted into a royal residence for a time, first, for Henry’s fourth ‘wife’, Anne of Cleves, whose plain appearance put the King off (the marriage was never consummated, and duly and quickly annulled). Ironically, this was the beginning of the end for Cromwell, who had arranged the nuptials. The by-then ungoverned fury of the King turned against his ever-loyal minister, and Cromwell was soon beheaeded.

Anne, again in one of thos ironic twists of fate, the wife-that-never-really was, outlived the rest of Henry’s wives.

The Abbey was used for a time as by Henry’s daughter by Anne Boleyn, Elizabeth; then, afer that, as a ‘noble’ house, with quite a garden, but soon fell into disuse, and left, as were so many others, to ruin, a symbol of what the once-glorious faith had become in England.

As Newman prophetically declared, Protestantism by its very nature descends into indifferentism, unhinged from a central and infallible teaching authority. I, for one, am not sure at this point what principles modern Anglicanism stands for, which is likely why so many are now converting back into the fold of Catholicism.

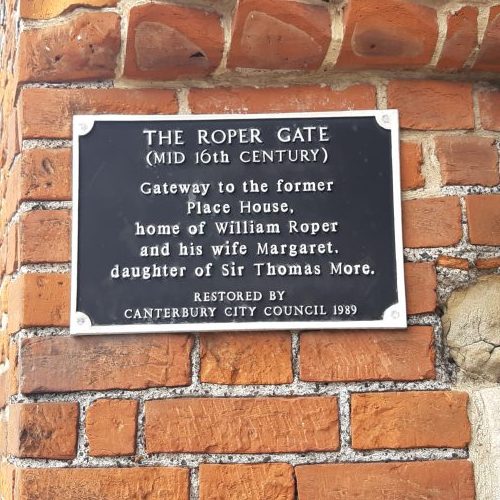

A final word about another martyred Thomas, More, whose head, I was surprised to discover, after being displayed on London bridge as a warning to other potential ‘traitors’, was entombed in the family parish of Saint Dunstan’s, nearby the house of his daughter Margaret, who had married Will Roper. (A plaque still stands outside their former house).

Saint Dunstan’s, like most other churches, was turned to Anglican use, and one is surprised to see that the small, stone mediaeval church is now bedecked with all things More, from stained-glass images, to his resting place roped off, candles burning, a veritable ‘Catholic’ shrine.

Saint Dunstan’s, like most other churches, was turned to Anglican use, and one is surprised to see that the small, stone mediaeval church is now bedecked with all things More, from stained-glass images, to his resting place roped off, candles burning, a veritable ‘Catholic’ shrine.

Like Becket, I wonder if the head of the good Christian humanist there under the vault, is smiling at the irony. The Faith really is indestructible, and what allows Anglicancism to survive, like any other religion, is its connection to the universal truth and beauty of Catholicism. (Which is why the newly-instituted Anglican usage is so attractive, evoking the beauty of Tudor-era Catholicism; Henry was nothing if not a staunch stickler for liturgy).

More, like Becket, knew that he was the king’s good servant, but God’s first. Henry could have his head, but his soul, like the Church, was God’s alone.