Pope Benedict XVI, in his second encyclical, the 2008 Spe Salvi (Salvific Hope) offers a distinction from the Letter to the Hebrews: We as Christians do not place not our hope on the hyparchonton – all the goods and securities of this life, the bigger barns filled with food – but the hyparxin– the true ‘substance’, the treasure in heaven that never ends. This is why saints could face martyrdom not with simple stoic resignation, but with joy. We must have our hearts – our minds, wills and passions – set on the hyparxin that is Christ and His teaching, and not on the ‘goods’ of this world.

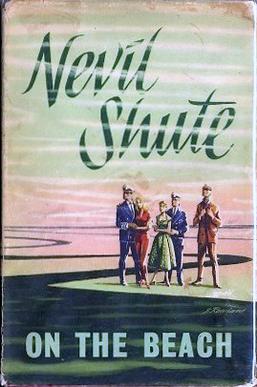

It’s in light of this teaching that I just read Neville Schutte’s 1957 novel On the Beach, which was made into a successful film in 1959 with Gregory Peck (with remakes since; spoiler alert for what follows, if you don’t know the plot). There has been a world-wide nuclear war, between China the U.S., and various other nations, which spiraled out of control, thousands of bomb dropped, many of the ‘cobalt’ variety, designed to unleash massive amounts of radiation (such bombs do exist, although they’ve apparently never been tested, they’re so dangerous, but not as dangerous as here portrayed). The resulting radiation cloud has killed everyone in the northern hemisphere, and it’s slowly making its way to the south. Those in Melbourne – where the story takes place – will be last to go. The plot unfolds as the residents await inevitable death by slow radiation poisoning in a few months’ time.

What would you do? Panic? Pray? Weep and mourn? Party like it’s 1999?

Whatever people would really do, in the novel, they live their lives more or less normally, at least the main characters, going about their business, many blocking out of their minds the obvious devastation to the north. There are glimpses of such, as an American nuclear submarine makes its way to the west coast of America, and sees some of the devastation from the shore.

But those in Melbourne live life to the full, with parties, sailing, car races, and family life. There is some redemption, of the natural sort, acts of kindness and solicitude. In one major plot, touching in its own way, a young woman, drowning her despair in alcohol, befriends the captain of the American nuclear submarine, and gets her life together. The only physical affection they show are a couple of chaste kisses, as he considers himself still married to his wife back in Connecticut, even though she is obviously dead. He lives in a quasi-fantasy world, that he’s going to return to them, and scuttles his submarine in the end with some toys on board for his two children, like some pharaoh buried with his jar of honey. He might need it; one never knows.

In the end, as August approaches and the radiation hits, people develop the inevitable symptoms. They all commit suicide, ingesting a government-issued pill that causes instant, and painless, death. It’s all presented in a very rational way – after all, why spend lingering days or weeks, dying a blood-and-filth-soaked wreck with no medical attention or alleviation of any sort?

Why, indeed, is the very question.

The world is not going to end this way – it will do so only with Christ’s return in glory, to segue back to our Advent theme. This is a story almost devoid of real hope, of the natural or supernatural sort. There is no mention of Christ, and religion comes up only a few times. The submarine captain attends two Church of England services, but later admits he’s not religious. And the woman, dying, slightly inebriated, mumbles a half-remembered Our Father as she swallows her euthanasia pill. That’s it.

There are of course parallels to our own agnostic era a half-century on. I couldn’t help but think of Covid as I read, with analogous threats of a vague, nebulous fetid poison drifting down from the ‘north’ (i.e., China). If this novel signified the secular Australian mindset decades ago – and things have not improved since – no wonder so many submitted to a vast prison state, giving up their freedom for living a few more days.

The Christian view – still alive and well amongst many Aussies! – is quite different. Suffering and death, and the constant risk thereof, are not only an inevitable part of this life, but they are very means to eternal life. Euthanasia is verboten to a Christian, and only seems rational if this life is all there is, and no resurrection awaits. But, then, if that’s the case, as Saint Paul says, we are of all men the most to be pitied.

It’s not the case. There is eternal life. But deliberate suicide closes us to that life, which is open only to those who follow God’s will, which includes the manner He has chosen for our death, faced with courage, confidence and serenity, whatever suffering it might entail. He always provides the grace.

And it’s not just individuals. There are subtle ways of committing societal suicide, a kind of communal living death, in fear and despair, to ‘control the climate’ and ‘keep everyone safe’? Safe for what? And what’s this planet for? To live a locked-in life of quiet desperation, in some sort of pod-like apartment, avoiding Covid and carbon emissions at all costs, eating mushed insects, before taking – or being force fed – our own version of the euthanasia pill? Give me the the radiation cloud.

Au contraire, mes amis! We were made for freedom, to attain eternity, to worship, to pray, to gather, to form families, to build houses and communities, to flourish and prosper. Yes, our demise is always on the horizon, but that itself paradoxically gives hope. But we must live well, so we may die well.

At least Schutte’s book get some part of the living well right, but not so much the dying. My advice? Don’t take the pill. Don’t give up. Fight on to the end. There’s always hope, and heaven awaits.

See you all there, Deo volente. +