The significance of today’s Gospel, about doubting Thomas—came home to me in a special way on 1 January 1975 when I was informed of the death of a good friend. His name was Lynn Edwards, and he had died in his sleep the preceding night. His death was not completely unexpected for, although he was only thirty years old, he was a severe spastic. Fluid would collect in his lungs because of the contortions of his body, and that is what caused his death that New Year’s Eve. If I can claim to have known a saint, it would be Lynn. Consider his situation. For his entire life he had been strapped arms and legs to a wheelchair. At night he had to have the sheets tucked tightly around his body and to have heavy woolen socks placed on his hands to prevent him from hurting himself by the violent and uncontrollable spasms of his body. Despite these serious handicaps, he was the most even-tempered, agreeable and witty person I have ever known. Because of his condition he could not speak above a whisper, but whenever I presented my ear to his mouth, I heard an amusing comment about something odd or a grateful response to some simple kindness. He was a Catholic, and his strong faith had much to do with his acceptance of his plight.

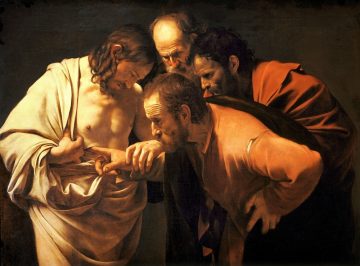

As a friend, I was asked by the family to preside at his funeral Mass, which I accepted as an honour. In pondering what to say in my sermon, I thought of today’s Gospel, and specifically of the fact that the body of the risen Lord bore the marks of his passion. On his hands and feet, as well as his side, were the wounds he had received in being crucified; but surely there were also the lacerations caused by the scourging, the marks on his head from the crown of thorns, and the bruises and scrapes from his having fallen and been beaten by the soldiers. Things that should have been too horrible merely to look at were rendered beautiful, even glorious, as tokens of the great love that had inspired Jesus to undergo these torments for the sake of our redemption. The disciples were enabled to regard the body of the risen Jesus, not with physical sight but with a moral vision, and this insight into the perfection of Jesus’s action made his mangled body supremely beautiful. A weak comparison would be the winkled and emaciated face of Mother Teresa. It was highly attractive because we knew that every crease on her visage had been put there by an act of love.

Hence, when the time for my homily arrived at Lynn’s funeral I was prepared. I said that, at the resurrection of the body, he would appear with his twisted body and distorted features, strapped to his wheelchair[i], but also that we would recognize his true worth because we would look on him and see through his body to the perfection of his soul. What I mean to say is that we should perceive in his disabled body the grace-filled means by which he had mirrored in his life the perfect sacrifice of Jesus. It’s as if a body could become transparent, so that the soul of the person would be manifest in its corporeal envelope. In contrast, mere physical perfection—an ideal specimen of humanity—would be hideous if a sinful way of life had corrupted that person’s inner being.

The fact is that our behaviour during our time on earth will determine our eternal destiny. We should, therefore, prepare ourselves for glory by honouring that mysterious union of spirit and flesh that we call a human being. Thus, when the resurrection occurs, the body will shine like the sun, as having been a vehicle of divine grace. It’s as if each act of virtue were an opening through which the radiance of God’s love can shine; and, correspondingly, every sin is a sort of closing off that will leave the sinner in a horrible and repulsive darkness. Well, God’s grace is ever abundant; he does his part. Our response to grace is what we contribute to, or subtract from, the final stage of our existence.a

[i][i] Saint Thomas might demur at this, for in his formulation, when we receive our bodies in the resurrection, they will be as God had originally intended them, without any of their imperfections – which are, after all, an effect of sin, in the broad sense. (Editor)