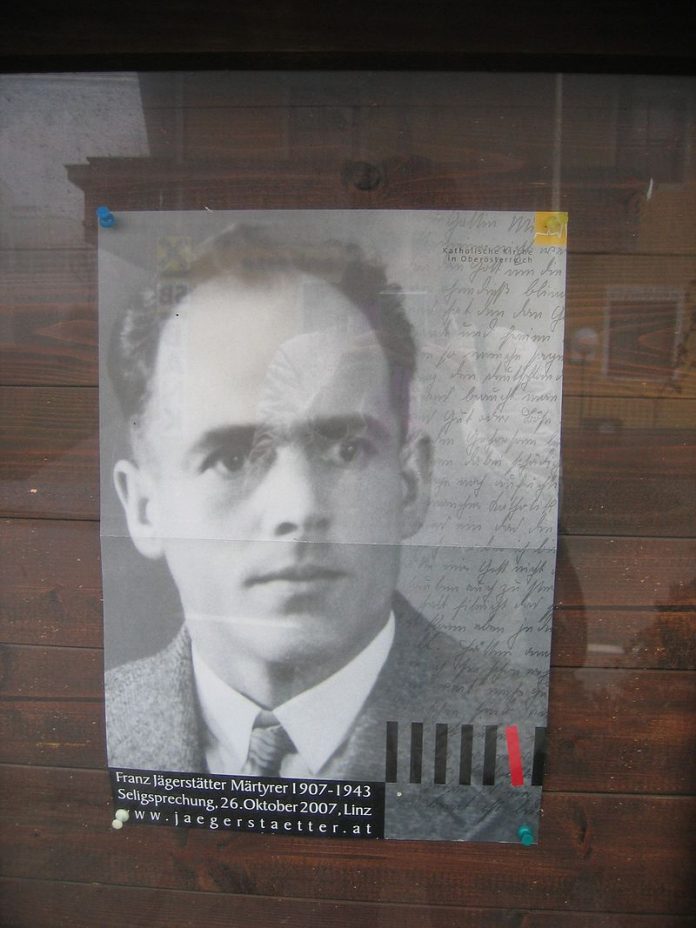

Saturday, May 21st, is the feast day of Blessed Franz Jägerstätter – the anniversary of his baptism – and it would benefit us to ponder the life of this great Austrian (and of whom a recent film was made).

Franz Jägerstätter was born on the 20th of May 1907, in the Upper Austrian region, in St. Radegund, which today is in the Diocese of Linz. He was the child of the unmarried farm maidservant Rosalia Huber. Being a maid and a farm laborer, she and the father, Franz Bachmeier, did not have the means to marry. Franz’s grandmother, Elisabeth Huber, was truly a loving, pious woman of wide interests. She bore the responsibility to raise the little Franz.

In those days there reigned a great deal of hunger and hardship in the region, particularly because of the First World War. At school, Franz was the victim of discrimination due to his poverty. In 1917, after his biological father was killed in the war, his mother tied the knot with the farmer Heinrich Jägerstätter, who, on marrying her, adopted his wife’s son. Franz was greatly inspired by Heinrich, becoming interested in books especially as an adolescent, including religious literature. Later on Franz inherited the farm from his adopted father.

From 1927 to 1930, we find Franz Jägerstätter working in the iron ore industry in Eisenerz (Styria, Austria). At this moment in his life Franz felt spiritually and religiously challenged, and he went through a significant crisis, questioning both his faith as well as his existential meaning. However, such a great challenge left abundant good fruit, so much so that in 1930, Franz managed to return to his home village with a strong faith in God.

Three years later, in 1933, Franz had a child, Hildegard, out of wedlock, Hildegard. Theresia Auer, Hildegard’s mother and a maidservant on a farm in the neighborhood; later confessed: “We parted from one another in peace; he begged my forgiveness.” It is beautiful noting that father and daughter nourished a good relationship with one another.

In 1935, Franz met Franziska Schwaninger, a farmer’s daughter from the neighboring village of Hochburg. After a year together, they immediately knew that they were meant for each other, and were married on Holy Thursday, 1936. It was at Franz’s suggestion that they travelled to Rome to spend their honeymoon there, receiving a blessing in audience with Pope Pius XI. Upon their return, they together ran the Leherbauernh farm. Franz’s marriage with Fraziska signalled a turning point in his life. In the words of his neighbors, Franz Jägerstätter became a different man. The couple started to pray together, the Bible their book of reference for everyday life. Franziska herself confesses regarding this time: “We helped one another go forward in faith.” From 1941, we find Franz Jägerstätter as the sacristan at St Radegund. The couple had three beautiful daughters: Rosalia (*1937), Maria (*1938) and Aloisia (*1940). Franz Jägerstätter once said: “I could never have imagined that being married could be so wonderful.”

From the very beginning, Jägerstätter did not deem it right to support and cooperate with the horrible Nazi regime, which took Austria in its hands in 1938. For Franz Jägerstätter, following Pius XI, Christianity and Nazism were totally irreconcilable. Furthermore, Franz Jägerstätter dreamt a horrendous dream which he deeply felt it was a warning to him to refute Nazism completely. He wrote:

“I saw [in a dream] a wonderful train as it came around a mountain. With little regard for the adults, children flowed to this train and were not held back. There were present a few adults who did not go into the area. I do not want to give their names or describe them. Then a voice said to me, ‘This train is going to hell.’ Immediately, it happened that someone took my hand, and the same voice said to me; ‘Now we are going to purgatory.’ What I glimpsed and perceived was fearful. If this voice had not told me that we were going to purgatory, I would have judged that I had found myself in hell.”

According to Franz Jägerstätter, the train symbolizes National Socialism (‘Nazism’) with all of its sub-organizations and programs (the National Socialist Public Assistance Program, Hitler Youth, etc). As he aptly describes it, “the train represents the National Socialist Volk community and everything for which it struggles and sacrifices.” He reminisces that just before having this dream, he had read that some 150,000 young Austrian people had joined Hitler Youth. He narrates, sadly, that the Christians of Austria had never donated as much money to charitable organizations as they now donated to Nazi party organizations. Franz discerningly became aware that it wasn’t really the money that the Nazis were interested in, but the souls of the Austrian people. You either supported the Führer or you were simply nothing. Upon this awareness, Franz Jägerstätter confides, “I would like to cry out to the people aboard the National Socialism train: ‘Jump off this train before it arrives at your last stop where you will pay with your life!”

Greatly helped by his ongoing spiritual development as well as by his profession as a Third Order Franciscan in 1940, Franz Jägerstätter was conscripted to carry out military service, but was twice brought home by the authorities in his home village, due to his “reserved civilian occupation” as a farmer. Franz was adamant in not obeying a third conscription order since for him he viewed fighting and killing, so that Hitler could rule the whole world, as a grave sin. His mother, relatives and several priests who were his friends all did their best to make him think otherwise. However, his wife Franziska, even if she hoped there would be a way out of the situation, supported him in his decision: “If I hadn’t stood by him, he wouldn’t have had anyone at all.”

In his numerous writings, Franz Jägerstätter detailed the reasons why he was acting the way he did. For him, to fight and kill people so that the godless Nazi regime could conquer and enslave ever more of the world’s peoples would mean participating in this heinous crime. Franz did not arrive at his decision of refuting Nazism haphazardly. On the contrary, his life story tells us that he prayed, fasted and sought advice. Moreover, he asked for a talk with the Diocesan Bishop of Linz, Joseph Calasanz Fliesser.

On his part, Bishop Fliesser was more concerned in saving Franz’s life. He told him that as the father of a family, his main task was surely not to decide if the war was justified or not. Although Franziska Jägerstätter accompanied her husband to Linz she was not present in his talk with the Bishop. Nevertheless she recalls the moment when her husband Franz came out of the Bishop’s consulting room: “He was very sad, and said to me: ‘They don’t dare themselves, or it’ll be their turn next:’ Franz’s main impression was that the Bishop did not dare to speak openly, because he didn’t know him – after all, Franz could have been a spy.”

Franz was conscripted for another time. Having said, while reporting to his regular military company at Enns on 1st March 1943, Franz Jägerstätter promptly affirmed: “that, due to his religious views, he refused to perform military service with a weapon, that he would be acting against his religious conscience were he to fight for the Nazi State…that he could not be both a Nazi and a Catholic… that there were some things in which one must obey God more than men; due to the commandment ‘Thou shalt love thy neighbor as thyself’, he said he could not fight with a weapon. However, he was willing to serve as a military paramedic.” This was written in the reason given for the judgment of the Reich Court-Martial, dated 6th July 1943.

Following this verdict, Jägerstätter was then taken to the military remand prison in the former Ursuline convent in Linz. Two months’ prison in Linz, together with the torture and bullying, brought on him a great crisis. This time, the young farmer found himself in the great danger of losing his faith altogether. However, the experience of happiness with Franziska accompanied him as an enduring sign of God’s presence amid this great turmoil.

At the beginning of May, Franz Jägerstätter was transferred to the military remand prison in Berlin-Tegel. After asking to be allowed to serve as a paramedic, his demand was turned down. On 6th July 1943, Franz Jägerstätter was condemned to death for “undermining military morale” and was also “stripped of his worthiness to serve in the army and of his civil rights“.

In his final days on earth, through Father Heinrich Kreutzberg, Franz learned that one year before the Austrian Pallottine priest Father Franz Reinisch, had likewise rejected to perform military service for the same reasons and had died for his convictions. Upon knowing this Franz felt greatly comforted. We are told that the Eucharist, the Bible and a picture of his children were of great comfort for him at this troubling time.

On 9 August, before being executed, Franz wrote: “If I must write… with my hands in chains, I find that much better than if my will were in chains. Neither prison nor chains nor sentence of death can rob a man of the Faith and his free will. God gives so much strength that it is possible to bear any suffering…. People worry about the obligations of conscience, less than their concern for my wife and children. But, I cannot believe that, just because one has a wife and children, a man is free to offend God.” Then, Franz Jägerstätter was taken to Brandenburg/Havel and beheaded.

Two pastors, Father Kreutzberg in Berlin and Father Joch¬mann in Brandenburg, considered him as a Saint and Martyr. In 1965, while working on the Pastoral Constitution of the Second Vatican Council, Archbishop Thomas D. Roberts SJ (Archbishop of Bombay, India from 1939 to 1958) said, in a written submission on Franz Jägerstätter’s lonely decision of conscience: “Martyrs like Jägerstätter should never feel that they are alone.”

History corrects itself. In fact, on 7th May 1997, 54 years after his execution, the death sentence on Jägerstätter was completely annulled by the District Court of Berlin. The annulment was tantamount to an acquittal and showed a moral and legal justification of his actions. The District Court based its decision on the assumption that the Second World War did not benefit the interests of the people but, rather, the Nazis’ infamous thirst for power. As a result any person who, like Jägerstätter, resists a crime cannot be considered a criminal.

On 1st June 2007, the Vatican officially confirmed the martyrdom of the Austrian conscientious objector and a tertiary Franciscan, Franz Jägerstätter (1907-43). His beatification took place in St. Mary’s Cathedral (the ‘Mariendom’) in Linz on 26th October 2007.

Lord Jesus Christ, You filled your servant Franz Jägerstätter with a deep love for you, his family and all people. During a time of contempt for God and humankind you bestowed on him unerring discernment and integrity. We pray that you may glorify your servant Franz, so that many people may be encouraged by him and grow in love for you and all people. For yours is the glory and honor with the Father and the Holy Spirit now and forever. Amen.