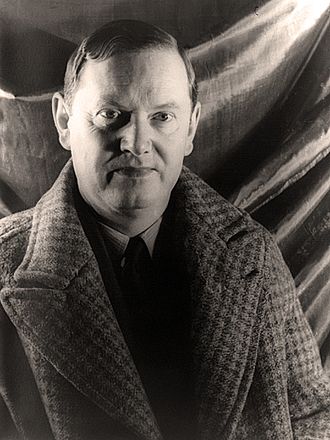

I was struck as I finished up reading over a small volume of letters by the great English writer Evelyn Waugh, author of such treasures as Brideshead Revisited, Love Among the Ruins, A Handful of Dust and numerous others, that this was the day he died, on April 10th, 1966, which was, fittingly, Easter Sunday.

Evelyn Waugh, a convert who entered the Catholic Church on September 29th, 1930 as a 26 year old, always loved the Mass, and his novels evince a deep immersion in his Faith. He is, in the truest sense of the word, a Catholic novelist, with an uncanny ability to show and not tell, to leave you with a sense that the Faith, even if it be hidden and submerged, is not only true, but holds everything together, without which, the centre truly cannot hold.

The slim book, published by Ignatius Press, is a series of letters, given and received, on Waugh’s thoughts on the changes in the Mass after Vatican II, implemented in his final years. Needless to say, perhaps, Mr. Waugh, was not, and we may repeat not, a fan of the ‘changes’ made in the wake of the Council – and that is putting things mildly

We should be clear that this was not about the Novus Ordo, which Waugh did not live to see, as it was not promulgated until 1969 (and then only in its editio typica Latin version, rarely ever said, with the English vernacular in 1974).

No, what he was writing, complaining and griping about, with his unmatched command of precise English, were the various ‘experiments’ with the Mass, flowing from disordered and disturbed elements in the ‘liturgical movement’, ‘experts’ armed with the nebulous and nefarious ‘spirit of Vatican II’, who took a metaphorical, and sometimes all-too-real, wrecking ball to the Mass of the Ages and its splendid accoutrements: high altars, vestments, chant, Latin, polyphony, litanies, stained glass, reverence. Iconoclasm it was, writ large, all the while adding much that was, shall we say, not so splendid, almost all of it of their own making, whatever their hearkening back to mythical ‘ancient liturgies’. We need not list the abuses, for we have all lived, and still live, through them, and the reader’s imagination may be even more vivid than mine.

In his own inimitable, acerbic way, Waugh criticized what was being done to the Liturgy, the outlandish, scandalous and bizarre. As he puts it in one passage:

In the Church of Christ the King, Oklahoma, the people instead of kneeling at the consecration and elevation of the host, crowd round the priest strumming guitars. All the tongues of Babel are to be employed save only Latin

And this was not the worst of it, for the worst was yet to come. We have pilgrimaged now as a people through the experiment now for fifty years – ten more years than the Israelites in the desert of Sinai – as this is the half-century anniversary of the official implementation of the Novus Ordo in 1970. Whatever one says about licit, reverent, beautiful chanted Masses in what is now called the ‘ordinary form’ – and I have seen any number of them, Deo gratias – most of us have suffered for years in ad hoc, clappy hands, extemporized, emotionalized, sentimental liturgies, flouting laws left, right and centre of the sanctuary, the bitter fruits of which, to this writer’s mind, are all around us, not least in our collective response to this crisis.

Evelyn Waugh saw back then where the radical change, one might say without much exaggeration the mutilation, of the Liturgy would lead. And he was not alone, including many non-Catholics, who saw the need, indeed the duty, of the Church to preserve the traditional Liturgy, as we would Notre Dame cathedral or Saint Peter’s itself – but even more so. A group of these elites, including Agatha Christine, penned this heartfelt 1971 petition to Pope Paul VI, claiming what a tragedy it would be to lose what we now call the ‘old Mass’. Well worth a read, signifying, like a testament frozen in amber to what we have lost.

Of course, all is not lost, for this crisis may bring many to their senses, and not, we hope, to lose their faith. As the saying goes, lex orandi, lex credendi, lex agendi. We believe as we pray, and we live as we pray and believe. This crisis is revealing things, not all of them pleasant, about how we ourselves, from the lowest of the laity to the most exalted of the episcopacy, have prayed and lived.

May we all learn what lesson God is teaching us, whatever betides afterward.