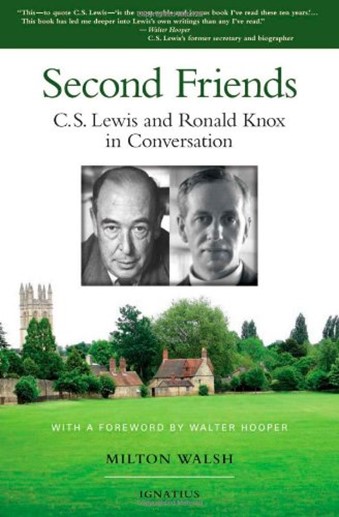

Some years ago I wrote rather a long winded play, Shaw vs Chesterton, an imaginary debate between two great friends, G.K. Chesterton and Bernard Shaw, with Hilaire Belloc moderating. I portrayed Chesterton and Shaw arguing their opposing views by way of passages lifted from their published works. Someone was actually kind enough to stage this project at the Cornerstone Festival of 1998 with Chuck Chalberg reading Chesterton’s part. Fr. Milton Walsh has done a similar project of examining in Second Friends: C.S. Lewis and Ronald Knox in Conversation (2008) the lives and views of two great Christian apologists who had met each other briefly in their youth and who would both become converts: Lewis, a one time atheist turned Anglican; and Knox, a former Anglican priest turned Catholic. While my staged encounter between Shaw and Chesterton was one of friendly combat, Fr. Walsh has approached Lewis and Knox as collaborating partisans for Christ who did not really know each other but surely knew each others work. This article explores only three of several topics dealt with by Fr. Walsh: the existence of God, the problem of evil, and miracles.

Two Converts

Lewis’ conversion experience resulted from a long search for ultimate truths that led him down many blind alleys. This alone caused him to re-examine whether the starting point – his rejection of his own Christian baptism – had been the first of his blind alleys. His search caused him to consider that Christian teachings were, above all others, the most sensible and satisfying he had ever experienced. Moreover, he discovered that if he persisted so much in searching for an Absolute, it was only because he had first fled the Absolute, and only later began to discover that the Absolute was searching for him as well, and would never cease the dogged pursuit of him, much as Francis Thompson described God in his poem “The Hound of Heaven.” The exact moment of conversion is one of those mystical experiences that are difficult to explain precisely, and Lewis was satisfied to point out that one morning, while en route to visiting the Whipsnade Zoo, he boarded the bus an atheist and realized in the course of disembarking that he had become a Christian.

Knox’s conversion experience was very different. He had never willfully fled from God, but had discovered in the course of seeking God that the Anglican Church had led him away from where he needed to go … to Rome. Knox certainly recognized many Anglican doctrines as true insofar as they agreed with and originated in ancient Catholic teachings. Yet where England’s Anglican Church had erred was in refusing to recognize the primacy of the Bishop of Rome who inherited his authority from St. Peter himself, the first Bishop of Rome. Like Cardinal Newman before him, this incontrovertible fact of history decided the matter.

Walsh asks what other reasons Knox discovered to make it necessary to become a Catholic. Knox was in youth both an intellectual and a romantic, one who sided much with underdogs (as Catholics clearly were in England) and who saw in the Oxford Movement conflicted Anglicans like himself, many of whom were unhappy with the dominant English Church and who were yearning for a path to Rome. Moreover, Knox could detect the rising tide of liberalism among the Anglicans, and that in itself was a sign to him that the world was not expected to conform to the teachings of Christ, but that Anglican Christianity was vigorously trying to conform itself to the world. The more liberal Anglican clergy had come to believe that watered down Christianity would be more appealing to the the masses who were increasingly infected with the skeptical bias of modernism. And then a central issue prevailed: where is the authority to be trusted regarding the deposit of traditional doctrines? Does it come from Rome or from London? Until the reign of Henry VIII it came from Rome, but increasingly, traditional doctrine was being re-interpreted according to the “experience” of modernity. (Knox and Lewis would both be shocked by the extent to which current modernity has not just watered down, but actually transformed much of the deposit of Anglican doctrine into something they would hardly recognize as orthodox Christianity.) Desperate and undecided, Knox realized by the fifth anniversary of his priestly ordination (that is, the Anglican orders, ed.) that he in good conscience had to take that dramatic step through a certain theological door into the Catholic Church.

Both Lewis and Knox were advocates for the mysteries of religion, but also advocates for aligning these mysteries with the power of reason and imagination. For example, the Eucharist cannot be just simply described at the figurative presence of Jesus, but as the Body and Blood of the Redeemer; and if one must borrow from Aquinas and Aristotle, the language of “substance” and “accidents” that makes this more intelligible, it is very reasonable to do so. Walsh puts it succinctly: “How the mind and heart interact is crucial to the question of believing.” This is not to repudiate the necessity of true faith, without which all the reasoning and imagination in the world cannot sustain or justify divinely revealed truths that are finally beyond our grasping.

“Proving” God

According to Walsh, both Lewis and Knox understood the distinction between those who accept God as a given and those who do not accept God as a given, in both cases there being no particular need to prove or refute God. The case for proving God generally arises when doubts arise, or traumatic experience (such as the experience of suffering and evil) give rise to the need for proof. The believer and the unbeliever are always capable of doubting their own premises, and at such points of doubt will seek intellectual verification for belief or unbelief. The believer will construct syllogisms that advance faith, and the unbeliever will seek to punch holes in those syllogisms. But neither Lewis nor Knox believed for a moment that God could be proven or refuted by a mere syllogism.

The existence of God must not merely be known, it must be experienced. The role of religion is to provide that experience, nudging it into existence and nurturing it. For Lewis it was important to give credence to the universal spiritual thirst that is quenched only by allowing the holy water of religion to be administered. Though various religious myths will come into being all over the world, and though they seemingly have little in common with each other, they nonetheless point to a reality beyond the world that is calling us to itself even when its call is mysteriously vague and jumbled with the images of this world. That is to say, religion is like an instinct that is trying imperfectly to understand itself, and therefore is unlike the instinct of all other creatures on earth.

Knox does not follow Lewis’ logic. Every religious experience is personal, and therefore cannot be a proof of anything for anyone else. We are not required to accept the religious person’s testimony that God exists because he feels God in his heart. Multiplying those experiences by the millions of people who have had them does not advance the argument either. For Knox something more was needed, an intellectual conviction based upon solid reasoning that some one Thing or Person is behind all of creation. This kind of wonderment must have happened to Adam when he first came to be aware of himself and wondered mightily about how he came to exist and why. As Knox said of Adam, “His strangest adventure was when he met himself.”

The plausible deniability of a Mind behind the universe was argued by Bertrand Russell, who pointed to the infinite complexity of operations within the universe as a way to explain that things seemingly too complex not to have been designed (like human beings) might come into existence quite by accident over a very long time. Knox found this argument exceedingly strange. In the first place, why should the human spirit be ordered by mindless molecules to exist, and why does this same spirit continually order molecules to obey its commands? Why does this same spirit look for a Cause of itself far more complex than mere molecules; and why do the molecules themselves point to a cause more complex and powerful than themselves, a Mind that governs all creation?

The Five Ways

C.S. Lewis for his part regarded the natural world not as intelligent, but as intelligible, a fact that Einstein also was surprised to discover. But this intelligibility alone does not require us to conclude there must be a God who made the universe to be understood. Lewis regarded the traditional five ways of Thomas Aquinas to prove the existence of God as coldly intellectual and therefore insufficient. Yet, Walsh assures us, Lewis’ own library included the works of St. Thomas, and he may have frequently visited them as is suggested by the fact that that some of his own arguments for God resemble those of the Angelic Doctor.

Knox found Aquinas’s third proof the most persuasive. All things exist only as possible things. They come into being and cease to be. But if there were no necessary cause that generates the coming and going of things, the possible beings would never come to be. Aquinas calls this necessary cause God. Knox and Lewis both found the fourth proof attractive in that it equates God’s being with His absolute goodness. Hence the existence of morality and conscience can only be explained as originating outside the soul and imposed on the soul by a higher power, which Aquinas calls God. Lewis found this argument more compelling than the so-called First Cause proof. Knox concurs; we judge Hitler as a proof that both God and the Devil exist because we see personified evil raging against God in the course of Hitler’s cruel regime.

Both Knox and Lewis found the fifth proof of Aquinas reasonable enough. There is too much order (too much natural law) in the world not to infer that the cause of all this order must lie outside the natural world. Why does the world not seem chaotic rather than ordered? (Or as Aquinas had put it in a comment on Aristotle’s teleology: “Nature is nothing but the plan of some art, namely a divine one, put into things themselves, by which those things move toward a concrete end: as if the man who builds up a ship could give to the pieces of wood that they could move by themselves to produce the form of the ship.” Commentary on Aristotle’s Physics, Book II, Chapter 8). The single best case for lack of order in nature resides in the sub-natural world of the atom, which is less predictable and more random. But, Lewis asks, if there is a door to the sub-natural world, why can there not just as well be a door to the supernatural? And why could there not be standing behind that door the Creator of all things Who has designed the best of all possible worlds?

That question still remains, the one that plagued the seventeenth century Deist thinkers: is God a Thing or a Person? That is, we know we cannot get to know God up close and personal, so how are we to relate to Him? Since God is outside all time and space, a great chasm of understanding exists. The unbeliever is satisfied with this chasm, and considers it a nuisance to even have to think about it. Easier, more practical, and much more pleasant it is to rid ourselves of metaphysics altogether and wallow in the muck of materialism and pleasure seeking. But Knox makes of the Sun and its planets a metaphor for God. The light of the Son exists, without which we would not exist. We cannot stare directly into that light, but we sense its abiding presence in the ways it illuminates all things around us, continually bestowing upon us good health and good cheer. The light of God always shines, even in the darkness; even in the souls of those who would forever shut their eyes to it.

Evil and Suffering

The problem of evil, Knox points out, is the most critical issue that leads either to lack of faith or loss of faith. The death of a loved one, war, famine, floods, earthquakes all contribute to the belief of many that a loving God does not govern the world, or that there is no God at all. For Knox this conclusion is not warranted. It suggests intellectual laziness because it does not stand up to the proofs for God. The mystery of evil does not disprove the existence of God by itself, so its weight tends rather light by comparison with the proofs for God, and throws us into the position of admitting only that evil is a mystery wanting a solution.

Moreover, Knox fully understood that God’s benevolent powers were limited by the gift of free will. He made us so that we could choose between good and evil, and we made ourselves to choose one or the other. But this answers only half the problem of evil, the moral half. How do we account for the other half, the half that includes horrible natural disasters in which thousands might die all at once through no fault of their own? For Knox there is no easy answer. Perhaps the suffering of Innocence itself on the cross for our sake alone can show us that God’s love is more profoundly mysterious than innocent humans suffering from natural disasters. Christ does not ask us to suffer more than he himself was willing to suffer on the cross, but in the case of natural disasters, he also does not always deprive us of the experience for a reason unfathomable to us.

On this point Lewis agrees. Natural laws are made to be obeyed. If nature’s obedience to those laws (that produce earthquakes for example) gets in the way of our happiness, God could intervene, but only by a miracle. Must we expect God to intervene in every instance of natural disaster? In that case, the natural laws seem to lose their efficacy. It would be as if we could change the rules of chess every time we sense the loss of a piece. What then would be the point of rules (or natural laws) at all? One might add that the fate of the soul is of greater concern than that of the body. We are all going to die anyway, whether by old age or by war or by natural disasters. (As Pascal observed, it matters how or when we die, but not so much as it matters that we care for our soul as if we had but eight hours left to live, so that we may be ready to enter eternity on God’s terms, not our own. The importance of our readiness to be rewarded in eternity hugely outweighs the importance of any tragic manner by which we may end our lives.) Only those without faith must regard death by natural disasters as the ultimate tragedy, for they see life robbed of it fullness, the only fullness it could ever have.

Lewis and Knox both recognized the existence of suffering as an evil, but they also recognized that good can always be drawn from suffering. Every child hates discomforts of every kind, especially a parent’s discipline for misbehaving. It is the raging of the self against authority that makes us miserable and rebellious. But this is a condition of the childish mind, which refuses to recognize good in any suffering, not even the dentist’s pull of an aching tooth. As Knox put it: “… there is no value without struggle. All the ardors and splendors of life are mixed up with doing things that are hard to do.” Lewis also recommended that we consider much suffering to be a call to renew our relationship with God, and it is no accident that many an ardent atheist might, suffering the imminence of obliteration on his deathbed, call out to God and repent his unbelief. God sends affliction to those who need it. Heartless as it may seem, even the death of a mother or father or child can be God’s way of calling us back from the superficial vanities of this world.

While much suffering may seem pointless or gratuitous, Knox sees all suffering as capable of producing good. The person who dies a terrible death might be atoning for a horrible life of sin (what goes around comes around); or it might be that the suffering attached to one’s sins in Purgatory might be assuaged or even canceled by intense suffering in this life. As Knox puts it: “Suffering, as we see it in this world, must be the wiping out of a debt; otherwise we should go mad thinking of it, so unevenly distributed. If some of us should have to suffer more than most of us, there must be compensation for that in the world to come. If you will not grant me that, then I will go out into the street with the atheists and rail at my God.” Indeed, if great pain can help to wash away our sins, there is no greater exemplar of undeserved suffering than Jesus on the cross, who by his suffering washed away the permanent stain of original sin…. So it is with suffering in human lives; an evil thing in itself, it becomes a good thing when it is transmuted, by the love of God, into a glowing focus of charity.

Are miracles possible?

Fr. Walsh rightly points out that the whole mindset of modern man is against the possibility of miracles. After all, miracles suggest a supernatural force at work in the world, and modern science will have none of that. Thus, the view of the early Christians that Christ did indeed work miracles as a proof off his divinity carries no weight in the scientific community. Many of those miracles are viewed as over-the-top story telling fables designed to wow the plebs. As both Knox and Lewis agree, the anti-miracle camp do not espouse science, but rather a materialistic philosophy. Since science confines itself to the natural world, it can have no say as to what God can do in the natural world.

Since creation itself is a miracle (no scientist has ever been able to scientifically explain the origin of the world – the Big Bang – as a natural event) everything, including the fall of a sparrow to the ground, is part and parcel of that miracle. Or as Knox put it, “A miracle cannot be probable or improbable; it is either possible or impossible.” Those who say it is possible have a burden of proof; but those who say it is impossible also have a burden of proof, and proof of the latter position is impossible to supply (since it is not possible to prove God does not exist) whereas proof of the former will be found in the testament of those who witnessed the hand of God performing marvels beyond the laws of nature. The real question, then, is whether these testaments are to be taken as credible and true.

Certainly Jesus raising Lazarus from the dead had to be viewed as a miracle, since he had been dead four days. There were witnesses to that event who doubted the possibility of raising Lazarus, and who reminded Jesus that if the tomb were opened there would be a great stench with which to contend. The revival of Lazarus and other miracles of Jesus encouraged attentive crowds to form around him and a formidable following that worried the Jewish and Roman authorities.

Indeed, the coming of Jesus into the world was a matter of God entering his creation. If Jesus expected himself to be accepted as the Almighty, it was only reasonable that he should suspend the laws of nature that he had created (even raising himself from the dead) to prove his authentic kingship over the universe; not only that he had a right to be taken seriously, but that, in view of his awesome powers, he had a right to command and to be obeyed. One is reminded of the old saw that you might have to smack a mule on the head with a 2×4 just to get his attention. The miracles of Jesus smacked the stubborn heads of many unbelieving doubters as they had not been smacked since the days of Moses.

Having read perhaps too much of Hume and Locke, Thomas Jefferson decided to publish his own version of the New Testament, excluding the miracles of Jesus. It must have been a dull read, for Jesus was now reduced from a divine Prophet and Saviour to a mere well-meaning philosopher with no more authority to command than any other of his ilk. As Knox remarks: “Put Raphael down at a street corner as a pavement artist, what proof can he give of his identity but to paint like Raphael? Bring God down to earth, what proof can He give of his Godhead but to command the elements like God?” Jesus exerts authority through miracles, and either He truly was sent by the Father to do so, or using the prowess of a magician he deliberately deceived his followers, a conclusion difficult to fathom given the sublime truths He uttered.

Without question the greatest miracle of Jesus was the Resurrection. The last part of each Gospel dwells on the aftermath of the Crucifixion, which was the story of a Man who had died and risen in glory. This was a lesson and a promise to all who would believe, that they would share in the glory, no matter how harsh and painful a path they had to follow to achieve it. Many wild and absurd explanations for the Resurrection have been offered by those who refuse to believe it, one of them being that the disciples stole his body from the grave, then concocted a story that he had risen from the dead. Even this supposed deception lacks credibility. In order for the authorities to end the rumors of His resurrection, something approximating what had been done to Jesus would have likely been done to those disciples as soon as they put out such a story. Why would the disciples have invited much danger to themselves if Jesus had not truly fulfilled his promise to rise in three days?

Having seen that promise fulfilled, the disciples realized that they too could share in this miracle of resurrection, and that Jesus had proved it by returning to them and sending them to go out and baptize the whole world. This is why the Gospel came to be called the Good News. We will all be resurrected to a new dimension of life radically different from the present one, a dimension in which all will be revealed to us (though perhaps for some of us the news will not be so good). The risen Christ met his disciples in “the ordinary circumstances of life.” But they believed they would meet him again in the extraordinary circumstances of Paradise. If the Good Thief could be promised that much, why not all of us? And so the disciples carried on their own legacy of miracle-working as a proof that the power of Jesus was in them too. It was in them because they believed enough in Him to die for Him. But that’s another truth unbelievers will find hard to swallow, and they will try to explain the martyrs away as no more than victims of a self-destructive, contagious, and “divine madness.”

Second Friends is chock full of brilliant analyses by Knox and Lewis on other themes as well; including the Church, Prayer, Gospels, Love, and Last Things. This book should be required reading for every serious student of Christian apologetics.