The great bishop and doctor Ambrose (340 – 397) is known for many things, not least his role in the conversion of the great Saint Augustine. When he was born, a swarm of bees covered his mouth and face – quite a horrifying thought – but Ambrose’s father said to leave them alone, for they signified that his son would be gifted in some way with greatness.

Like his protégé (both of them later declared the first doctors of the Church) he spent the first portion of his adult life as a layman, and not even yet baptized. It was in 374, as Governor of Aemilia-Liguria in northern Italy, that he went to a church to quell a conflict between Arians and Catholics over the choice of the next bishop. As the cultured and educated Ambrose, well trained in law and rhetoric, began to speak so persuasively, the restive crowd began to chant in unison, ‘Ambrose for bishop!’ There is nothing wrong with a democratic choice for our bishops, or by popular acclaim, so long as the Holy Father approves and ratifies the choice. In fact, such a method may go some way to improving our episcopal candidates, for the sensus fidelium may have more sense than whatever process is now used. I’m sure many readers have in their mind a vigorous, orthodox priest who would make a fine bishop, but never will in our current milieu. Certainly, it worked well in Ambrose’s case, one of the greatest pastors in the history of Christendom, known not least for his composition of chants – not specifically the task of a bishop, but a fitting accessory – more beautiful and ornate than the one which summoned him to office.

Still technically a pagan, but with Christian sensibilities, Ambrose fled into hiding from the mob – even back then, few wanted to be a bishop – but eventually relented with the emperor’s urging, accepting in quick succession baptism, confirmation and ordination, after which, as bishop, he adopted an ascetic lifestyle of prayer, study, writing and pastoral work.

He was a staunch foe of the aforementioned heresy of Arianism, which claimed that Christ was not truly God, just an exalted creature, sort of an embodied angel. This was both a Christological, as well as a political heresy, lingering long after its condemnation at Nicaea in 325. As someone once reflected, Arianism was a fitting foil for power hungry emperors and potentates, who could ‘reduce’ Christ to a non-divine creature, who could then be manipulated to their own purposes, and so take all the authority for themselves. For if Christ is truly the Omnipotent God, the Pantocrator, to Whom every knee must bow, then the emperor’s power is rather limited . The insidious implicit influence of Arianism is still with us, as our world leaders shrug their shoulders, and turn away from Christ and His message; at least, for now…

Ambrose stood up to the emperors of his day, mired in Arianism, drawing clear lines in the

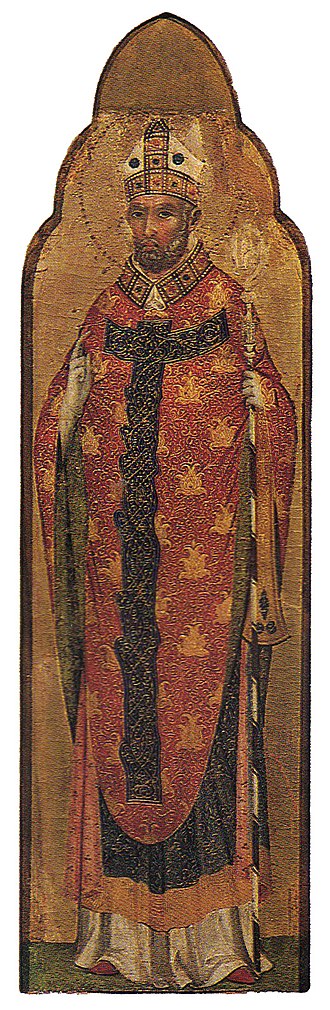

(Anthony van Dyck, 1619)

wikipedia.org

sand for the limits of the State’s authority. But it was not just heretics. When the orthodox emperor Theodosius – who made Catholicism the official religion of the empire in 381 with his Edict of Thessalonica – allowed his troops to massacre the rioting civilians of that city a decade later, in 390 (they had taken refuge in the Hippodrome), Ambrose wrote a clear, yet charitable, letter to the emperor, stating that he would be forbidden Communion until he repented, even blocking the doors of the cathedral in Milan. And, guess what? Theodosius realized his sin, and the firm action of his bishop likely saved his soul.

What might we give for such an Ambrose in Canada, who would confront our wayward politicians! Or America, Britain, Ireland…Anywhere!

Ambrose is also famous for consoling the distraught Monica, weeping over her prodigal son, saying the child of such tears could not possibly be in lost in the sight of the good God. Sure enough, it was Ambrose, according to tradition, who eventually baptized Augustine, after the restless African spiritual wanderer finally went with his mother to Milan to meet the famous bishop. They found him poring over a text, amazed that Ambrose read ‘without moving his lips’. But it was Ambrose’s explanation of the Faith that finally tipped Augustine’s stubborn will, to accept the grace of God. What Ambrose said of the love of God may be said of any human love: Love is like a shadow, one can only catch it by falling into it.

And where would we be without the Doctor of Grace, his works far surpassing what any one man might consume, never mind produce? It was Ambrose who catechized and baptized Augustine, and they are forever linked in history, rejoicing together, with Monica and all the myriad of heavenly saints and angels, now in heaven.

But it is Ambrose we celebrate today, one of the great Church Fathers, whose inimitable works gained him a place amongst the Doctors. He wrote on almost every subject then known, and, hence, is a very fitting patron for the liberal arts. Amongst his many spiritual treatises, his devotion to Our Lady makes him a fitting saint on this vigil of her Immaculate Conception. Ambrose was also a poet and hymnographer, credited with introducing hymns into the Liturgy, and we will leave you with the words and chant of his glorious Advent reflection, Veni redemptor gentium, used in the Office of Readings in that final novena before Christmas, from December 17th to the night before the great feast:

Veni, redemptor gentium;

ostende partum Virginis;

miretur omne saeculum:

talis decet partus Deum.

Come, Redeemer of the nations;

show forth the Virgin birth;

let every age marvel:

such a birth befits God.

Amen.