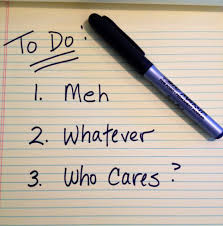

We live in slothful times. I don’t mean to say that our age is uniquely lazy, however common indolence may happen to be. Modern man can be lazy, of course, but he can, maybe even more often, commit himself to incessant activity, too. There may be ground to criticize the person who claims that he’ll rest when he’s dead, but we can’t accuse him of laziness. The busyness of modern life gainsays a claim to generalized laziness. It does not, however, gainsay a claim to deep-seated sloth – also called in the patristic literature, acedia.

Indeed, much of modern busyness is a result of such sloth/acedia. Acedia is not laziness; it is the erosion of spiritual vitality, which St. Thomas Aquinas defined as both a sickness about the good and a hatred of genuine human activity understood as the actualization or realization of the fundamental human function to love God and aspire to blessedness. Acedia is an evasion of God and of man’s purpose entailed by being created in God’s image (see Question 35 of the Secunda secundae of the Summa Theologiae as well as Chapter 2 of Jean-Charles Nault’s splendid The Noonday Devil). In A Brief Reader on the Virtues of the Human Heart, Josef Pieper puts this neatly: acedia means that “man denies his effective assent to his true essence, that he closes himself to the demand that arises from his own dignity, that he is not inclined to claim for himself the grandeur that is imposed on him with his essence’s God-given nobility of being.” The person who is excessively busy is excessively occupied with evading his true essence. Our times might not be distinctly lazy, but they are deeply evasive. We might even call this condition despair.

Beyond the busyness of work, acedia manifests in various ways, many of which are evident today: the garrulousness of social media; the curiosity of gossip, nowhere more extreme than in the preoccupation with celebrity; the mid-life crisis, by which one regrets and disavows all prior major life decisions (one doesn’t bother to regret minor decisions – we’re told to not sweat the small stuff, after all); the restlessness of a culture desirous of constant change and novelty: a new house, a new car, another vacation. Each manifestation of acedia – what the Church fathers called its daughters – is a clear example of distraction from and evasion of God and, by extension, of self, rightly construed. We fill our space and time with the banal precisely to avoid coming to terms with our humanity, which also, most importantly, means running away from our purpose: to glorify the Lord, to love God.

But there is one manifestation of acedia that strikes me as more prevalent today than the others, so much so that the others have come to be influenced by it: amusement. Social media is not only the site of constant chatter; rather, the chatter, even when – or especially when – it is contentious and combative, is amusing. Celebrities are fun, amusing us even in the triviality of their private lives. The person in a mid-life crisis doesn’t really aspire to more meaning and spiritual good, but to more fun and, too often, to the abandonment of the responsibilities essential to a meaningful life, like duties to spouses and children, which are now perceived as not only burdensome, but downright oppressive. And not only is change a new opportunity for pleasure, but imagining the change can itself be amusing: one watches television programs about home renovations, reads reviews of new cars, and spends hours listening to random people online regale them with stories of their travel adventures. Inspired by Josef Pieper’s Leisure: The Basis of Culture, where he characterizes the modern world as one of “total work”, I propose we are living in the era of “total amusement”.

By “total work”, Pieper doesn’t just mean that people work too much. He did believe that his contemporaries worked too much, so much so that they frequently neglected their human purpose to cultivate themselves in relation to God. They too often neglected leisure in favour of the hustle and bustle of the workaday world. Nonetheless, this it is not why he used the expression “total work”. More than work, “total work” refers to a conception of man, born of utilitarian and Marxist thinking, that reduces human nature and human value to work, to effort, to what can be measured, particularly in economic terms.

Pieper isn’t really worried about work as such, whether it is paid or unpaid, remunerated adequately or not, difficult or easy, satisfying or boring. Instead, he is asking about our humanity, about who we are and how we understand ourselves: “a new and changing conception of the nature of man, a new and changing conception of the very meaning of human existence – that is what comes to light in the claims expressed in the modern notion of “work” and “worker”.”

In the regime of “total work”, man is not perceived as made in the image of God; he is but a worker, a maker, a being that is productive or else an utter failure. Indeed, because man is characterized by effort, work, and making, he even makes his own self, his identity. He is his own project. Man is made in his own image – and, I suppose, remade over and again in the same.

I mean “total amusement” in a similar way to refer, not to the prevalence of amusements, but to a theory of man that has, mostly without awareness among its adherents, permeated the present age: man is a pleasure-seeking being who presumes to find his realization, his fulfillment, the completion of his life’s purpose not just in pleasure as such, but specifically in fun, in amusement.

But doesn’t this go too far? Surely, humans have always amused themselves when the serious business of life – work, care of family and of self, religious obligation – has been completed; man engages in recreation, a little harmless fun, to find temporary respite from the matters that matter most, which matters can be exhausting. When he has the time to, man seeks out amusements. I think of my father, who grew up on a farm with rocky soil in a communist country. He had little choice but to work very hard his whole life. He still does keep himself busy, though he’s long past the point of being physically able to exert himself as much as he’d like. Nonetheless, even at his busiest times of life, my father enjoyed having a bit of fun, sharing a joke with the boys after Mass or playing cards with friends on a Saturday night. A little amusement isn’t bad.

To be sure, the comfort of modern life for many of us in the West means that we have more time for recreation. Maybe we need to learn a few more card games to manage, but it doesn’t follow that life has been reduced to recreation, that contemporary humans understand themselves as fundamentally amusement-seeking beings. Maybe some of us amuse ourselves too much; maybe, as Neil Postman warned in the 1980’s, some of us are “amusing ourselves to death”. But that doesn’t mean we’ve accepted a false anthropology, does it?

This objection is right that amusement is not intrinsically bad, and that the nature of human life, including productive effort, means that some recreation is needed. This objection is also right that the historical fact that the conditions of modernity increase the opportunity for amusement doesn’t demonstrate that amusement is worrisome; in other words, more amusement isn’t the problem. The issue isn’t how much we amuse ourselves, but when and why we do so. It is possible to have no time for fun, while still being consumed by total amusement; I may never amuse myself while still living, albeit implicitly, as if I am, at core, made for fun. Again, the question isn’t how much fun, but when and why I seek it out. If amusement is what I pursue when the exigencies of life are taken care of, if my leisure time, which is the time left to me after I have completed what is needful, is devoted to amusement, then I do indeed understand myself as a being made for amusement – whether I admit it or not, whether I even have the time to practice it or not. I believe this is, indeed, the condition of the world today.

In the Nicomachean Ethics, Aristotle observes that all people believe that the purpose of human life is happiness, but most disagree about what happiness is. Some believe it is pleasure, some honour, some political action, and yet others that it is study. We can, Aristotle thinks, recognize that happiness is the human purpose when we see that it is the only human pursuit that contributes to nothing outside itself. Even knowledge, which is good in itself, contributes to happiness, whereas happiness adds nothing beyond itself – it doesn’t, for instance, make us smarter, let alone wealthier or well fed. What, then, is happiness?

It isn’t my goal here to make a case for some specific account of happiness, though I unabashedly admit that I believe is lies in beatitude. My point here is, rather, that the answer to the question depends on a theory of man. If happiness is the end of human life, then it is determined by the kind of being a human is. Those who presume to find happiness in pleasure believe man to be, at core, a pleasure-seeking being. If modern man has adjusted this answer by saying that happiness lies in fun, in having a good time, in amusement, then man is, accordingly, the fun-seeking being: man finds himself and his fulfillment in amusement. When that conception is widespread, we have total amusement.

When I teach Aristotle I make the joke that today the purpose of human life is shuffleboard. Why go to school? To get a job. Why get a job? To have money? Why get money? To buy things, like a house and mutual funds? Why buy a house and mutual funds? To accumulate wealth? Why accumulate wealth? To retire. Why retire? To take cruises, drink virgin margaritas, and play shuffleboard. It’s a silly joke – one of those that isn’t actually funny, but that a teacher makes to help illustrate some points. First, all human action aims at some ultimate end, not just an immediate end: namely, happiness. Second, who we are and what we value determines what we believe that end to be. If I happen to be wrong about that end, then my life, likewise, will be wrong; if I am unserious about the end, then it should be no surprise that my life will be unserious, too. Third, shuffleboard, as the stand-in for amusement for its own sake, is not an unreasonable guess to the question: what does contemporary man value ultimately? My students might not laugh at the joke, but they seem to understand and agree with the point: modern man aims fun, and he does so because he, however implicitly, understands himself as oriented, in essence, to it, to amusement. This is total amusement.

Returning to sloth – or acedia – we can catch sight of a remedy for total amusement. To argue that one should just stop having fun is not helpful, both because fun is not intrinsically bad and, more importantly, because restricting amusement doesn’t address one’s false anthropology. One can, I think, stop having fun and be left just as distracted because unfulfilled, neither pursuing the right end nor receiving the false end they mistakenly value. The remedy to total amusement is not less fun; it is a new anthropology, which also happens to be the old anthropology: man is the being created in God’s image.

Put differently, the remedy is the remedy to sloth: to receive the redemption that is offered freely through the incarnation, passion, death, and resurrection of our Lord. As Fr. Nault points out, acedia is opposed to faith, hope, and love. Thus, only in the fullness of Christian virtue is sloth defeated, not once and for all, of course, since humans continue to struggle against the temptation to sin, but it is defeated temporarily no less. And if sloth can be defeated, then so, too, can that daughter of hers, the one who is so powerful and influential today, the one who tempts us to evade God and ourselves, the one who persuades us to despair: total amusement.