In light of this festive season, in which we celebrate the manifestation of the Messiah in His birth at Bethlehem – and also, perhaps, as an oblique clarification of some comments made in the current Magisterium of late – thought I’d post a brief summary of the heresies that arose in the early Church concerning the Incarnation. Heresies there must be, wrote Saint Paul to the Corinthians, which seems odd, until we realize that heresies help us determine more clearly what we really believe. In Sherlockian terms, by removing all that is impossible – that is, contrary to the doctrines of the Faith – what we are left with, however improbable from our limited human perspective, must be the truth.

Gnostic Docetism:

The earliest heresies, from the first days of the Church, denied not Christ’s divinity, but rather his true humanity. Gnostic Docetism taught that Christ only appeared as a man (from doceo, which can mean to ‘seem’ or ‘appear as’). His humanity was, therefore, an illusion, of sorts, to help us understand or see His redemptive work. This was allied with dualistic heresies, denying the goodness of matter; after all, how could the transcendent and immutable God come in the form of ‘evil’ matter, all that having a human body entails? Perish the thought! God is pure spirit, and must only be so. But not so, said the great Saint Irenaeus, who battled these Gnostics, and that Christ ‘emptied Himself, taking the form of a slave, becoming like us in all things but sin’ is a central truth of our Faith. He, the divine Logos, was truly a Man.

Adoptionism:

In the century or two afterward, heresies did indeed arise that denied the fullness of Christ’s divinity. Adoptionism, attributed first to the eccentric Paul of Samosata (200-275), bishop of Antioch, taught that Christ was the adopted Son of God, but not truly of a divine nature; rather, he was an ordinary man shown special favour by God. Some versions of this heresy admitted that Christ may have become ‘divinized’, in a vague sense, but only after His adoption by the Father. This is still with us in various strands of Modernism that have arisen from the rationalism of the 19th century – along with the drivel that has flowed forth from Hollywood of late.

Arianism:

The pernicious heresy Arius (ca. 250-336), an upstart deacon at Alexandria, admitted that Christ more than human, indeed the highest of God’s creation, but He was still a creature. Arianism sort of thought of Christ as an exalted angel, very powerful, but just not quite God – sort of ‘second God’, to use Origen’s terminology – who took the form of a man to save us. The Arian watchword was ‘there was a time when He was not…”. They brought forth numerous Biblical passages purporting to support their theory (‘the Father is greater than I..’ and so on). But there are more passages, along with our great Tradition, that signify that Christ was true God from true God, for in the beginning was the Word, and the Word was God. Arianism, along with Arius himself, was condemned at the councils of Nicaea (325) and Constantinople (381), stating that Christ was of the same ‘substance’ or ‘being’ as the Father, that is consubstantial (homo-ousios, con-subtantialis), as we say in the Nicene Creed

The heresy continued to linger for centuries afterward, particularly amongst the Barbarians, who were evangelized and converted by Arian missionaries. Some attempted a compromise adding one iota to the definition, that Christ was homoi – ousios, which is ‘much like’ or ‘similar to’ the Father. But the Church was clear, and the homo – ousios stood, and still stands.

Apolliniarianism:

Apollinarius, bishop of Laodicaea (+390), held a Platonic view of Christ, that his human nature was composed of spirit, soul and body. The divine Person ‘took over’ what was highest in the human person, the spirit, while leaving the body and its animating soul human. However, if Christ lacked the highest power of man (basically the rational, spiritual power), then how could He be considered truly human? This heresy, which made Christ to be some sort of ‘zombie’, animated by a kind of ‘soul’, but ultimately moved around by the divine Logos, was condemned at Constantinople in 381.

Nestorianism:

When I ask students in class if Christ was and is a human person, most reply in the affirmative, making them, at least materially speaking, implicit followers of the heretic Nestorius (386-451), patriarch of Constantinople. He propounded the theory, which seems quite intuitive, that Christ was two persons, a divine one, and a human one. Nestorius’ watchword was that Mary was the mother of the human person of Christ, not the divine one, for how could a mere human give birth to God? Thus, we might call her Christotokos (the ‘Christ-bearer’), but not Theotokos (the ‘God-bearer’), a title attributed to her from time immemorial in the East. Christ, therefore, was both a human and a divine person. When asked how these two ‘persons’ in Christ were united, Nestorius replied that there was a ‘moral’ or ‘habitual’ union between them. But how does this type of ‘union’ differ from any human person’s union with the Godhead?

In response, the Church clarified that Christ was one, divine Person, who assumed human nature. Thus, Christ was not a human person, although He did have a human personality, and all that was requisite to a full human nature. Nestorianism was thus condemned at the Council of Ephesus (431), where Our Lady was also now and for all time proclaimed truly Theotokos, the Mother of God. Mary did indeed give birth to the Second Person of the Blessed Trinity, God, on that still midwinter night in Bethlehm, in His human nature.

Monophysitism:

Yet another heresy, sort of the other extreme of Nestorianism, came along soon afterward, begun apparently by a monk of Constantinople named Eutyches (380-456), who claimed that Christ was not only one divine Person, but He also only had one nature, which was also divine. That is, Christ’s human nature was ‘swallowed up’ by the divine nature, like the drop of water in the wine of the chalice. Other, perhaps less common, versions have Christ a ‘blended’ being, with the divine and human natures melding together to produce some kind of super-being. This heresy was therefore termed monophysitism, Greek for ‘one nature’, whether purely divine or blended, which reminds me of malt Scotch, for some reason. You may also read of this described as Eutychianism, after its quarrelsome founder.

This heresy was battled by Pope Saint Leo the Great (ca. 390/400-461). The great Council of Chalcedon (451) adopting a letter of Pope Leo’s – his famous Tome – proclaimed once and for all that Christ was one divine Person existing in two distinct natures, a divine and human, “without confusion, change, division or separation”.

The union of the two natures in Christ takes place in His divine hypostasis (or Person). Thus, the Incarnation is referred to as the ‘hypostatic union’.

Other lingering heresies:

After this definitive statement, there were still a few lingering heresies: Some tried to posit a human hypostasis in Christ that was not quite a person, not realizing, perhaps, that any human ‘hypostasis’ (that is, individual) must necessarily be a human person, so this was just a kind of Nestorianism, and condemned at the Second Council of Constantinople in 553.

Others tried to state that although Christ had a human nature, He did not have a true human will, for then this human will might act contrary to His divine will. This heresy was called monothelitism (Greek for ‘one will’). The Church, however, realized that without a true human will, Christ could not have had a true human nature. This heresy was battled by Maximus the Confessor (580-662), who had his tongue cut out and his right hand cut off for his defense of the truth. The good saint’s witness to the truth was not in vain: This heresy was condemned at the Third Council of Constantinople in 681.

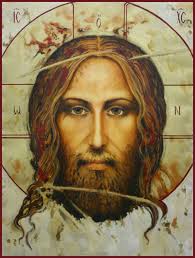

Finally, there was the heresy of iconoclasm that arose almost out the blue, which held that images portraying Christ, Our Lady or the saints were idolatrous, and thus should be ‘smashed’ (hence, its name). ‘Twas not quite out of the blue, but rather out of the harsh, anti-rational desert of Islamism, which condemns any portrayal not only of Allah, but of His Prophet. Emperor Leo III, the ‘Isaurian’, was particularly rabid in smashing the beautiful and beloved icons, and the people resisted. After much struggle and many martyrs, this heresy was condemned under the aptly-named iconophile, Empress Irene, at the Second Council of Nicaea in 787, but lingered on into the subsequent centuries, and had a resurgence at the Protestant revolt in the 16th century, and then in the heady days after the Second Vatican Council, whose texts were ignored, and a deranged ‘spirit’ took over, smashing altars, statuary – a manifestation, whatever the intention of the secondary human agents, of that eternal demonic rage against the Incarnation of the Most Holy Son of God, His Mother and all the saints, who nobly fought, not only of old, but are still struggling mightily against the powers of darkness…

Yes, and alas, these heresies that still linger in some form or another, as Christians, only lightly catechized, if at all, today implicitly hold some kind of Nestorian view of Christ. Others have a kind of monophystic approach, while others (e.g., the Jehovah Witnesses) hold a kind of Arian Christology.

But we, as Catholics, have the full truth of Christ, confessed in summary at the Council of Chalcedon, and still held by the Church today: Christ is one divine Person, the Logos, the Second Person of the Blessed Trinity, existing in two full and complete natures, taking on Himself all that was human – like us in all things, except sin. It is, indeed, a mystery, indeed the central Mysterion – and we will never fully understand how God could become Man, we can at least hold the basic principles of this ineffable truth without falling into heresy.

As Augustine says in his sermon for this Christmas Eve:

For what greater grace could God have made to dawn on us than to make his only Son become the son of man, so that a son of man might in his turn become son of God?

So rejoice in His blessed and joyous Incarnation! Our salvation is always near at hand.

And a very merry Christmas and Epiphany to one and all…