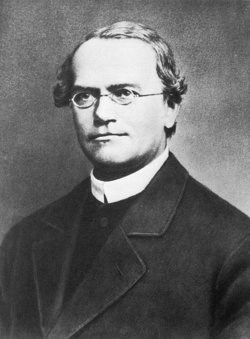

Gregor Mendel of Austria (1822-1884) was a young priest in the Augustinian Abbey of St. Thomas in Brno, Austria, who in his spare time he studied in his monastery garden the reproductive patterns of the garden pea. From these studies Mendel was able to determine certain laws at work which determine the inheritance of dominant and recessive character traits. Much of his later work required sitting at a brass microscope for hours on end until at one point he began to suffer from eye strain. As he complained in a letter to a friend, “Since ordinary dispersed daylight was insufficient for my work on the tiny Hieracium flowers, I made use of an illuminating apparatus, without thinking what damage I might do to my eyesight.”

Mendel eventually published in a relatively obscure journal several essays summarizing the mathematical laws of inherited dominant and recessive traits. As a result of his efforts, today Mendel is regarded as the founder of the science called genetics (the term was coined by William Bateson).

As with almost anyone who discovers a new science, at first Mendel’s work was largely ignored and did not finally gain the respect of the scientific community until sixteen years after his death. However, upon the rediscovery of his work by Bateson and others in 1900, the enormous significance of his studies had one of his early admirers declaring Mendel’s experiments worthy to rank with the atomic laws of chemistry, while another enthusiast declared Mendel’s laws to be no less important than those of a Newton or a Dalton.

Since the first publication of his ideas thirty-five years earlier, Mendel’s Laws had suffered an eclipse of scientific interest for two reasons. First, Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution seemed, by its emphasis on random variations in reproduction, to deny the existence of “laws” regarding inherited traits. In the scientific community the excitement aroused by Darwin’s theory made unlikely the chance that Mendel could be taken seriously. Darwin himself seems never to have been aware of Mendel’s groundbreaking discoveries. The “randomness” of Darwin’s theory seemed to push many toward the inference that God is not needed to explain the complex orchestration of Nature. Mendel’s genetics would have pushed randomness aside and restored the idea of order in nature just when biologists were getting comfortable with Darwin. Perhaps one of the great misfortunes in the history of science is that Darwin and Mendel never got together to compare notes.

The second reason for the general neglect of Mendel’s work is that he himself failed to develop further his complex theories or to vigorously promote them in the scientific community. At the age of 45 he was elected abbot of his own monastery, and was consumed for many years with administrative duties which blocked the pursuit of the research that had meant so much to him in his youth. Add to these distractions an endless and exhausting battle with the government over the new monastery tax that Mendel regarded as unconstitutional. Abbot Mendel was often heard by other monks to express regret at his lost opportunity to advance his unfinished scientific work. These complaints would often be followed by the exclamation, “My time will surely come.”

And come it surely has.

The science of genetics has grown far beyond what Mendel could have imagined in his day. In 1952 researchers discovered that DNA – deoxyribonucleic acid – was the molecule that controlled inheritance. Within a year Watson and Crick had cracked the genetic code of DNA. Because cancer is a genetic disease, it will now be possible to combat cancer by learning more about how and why cancer kills. Through the science of genetics great advances in law enforcement also have been made possible by lab technicians being able to match samples of blood, hair, and sperm with those of criminal suspects.

Today Mendel’s cemetery stone is so mold-covered his name carved on it can hardly be read. Not an impressive monument, yet he yearned for a greater one, as we can see from these prophetic lines of a poem he wrote in his youth:

The highest goal of earthly ecstasy,

That of seeing, when I arise from the tomb,

My art thriving peacefully

Among those who are to come after me.