Carl Sundell has a very a propos article today in Catholic Insight on the remarkable Frank Sheed (+1982), a Catholic lay apologist who emphasized the need of a properly formed intellect not just to demonstrate the rationality of the faith to others, but also to live it oneself.

The loss of intellectual formation is one of the direst crises facing the Church, for it is from ‘small errors in the beginning’, as Aristotle would put it, ‘that great errors eventually follow’. And Catholic intellectual formation is a rather specific thing, on which the Church has taught since her earliest days in that whole notion of a ‘liberal education’, properly understood.

Since the Middle Ages, the Church has prescribed the ‘scholastic method’, especially that of Saint Thomas Aquinas, along with all that is embodied within what is known as the ‘perennial philosophy’, valid ‘through the ages’, without immersion in which, along with at least a good smattering of all the ‘greatest that has been written and said’, one cannot really be considered ‘educated’, at least in the Catholic sense.

The lay Catholic convert author Flannery O’Connor, it is reported, read an article from Thomas’ Summa every night, and I dare say that most Catholics now wandering around (intellectually, I mean) have scarcely, if ever, opened its pages. We would benefit remarkably from following O’Connor, or, better yet, ensuring a proper education during our formative years.

The mark of an educated mind, Saint Thomas says, is the capacity to make the proper distinctions, so we can know the world as it really is, for only the truth can make us free.

On that note, Father Raymond de Souza has an article in the Catholic Herald on Saint Thomas More as a ‘martyr of freedom of conscience’. I have heard this claim before, and in the broadest of senses, there is truth in it, insofar as More protested his innocence, by the right to hold his own conscience and counsel free from taint, in the midst of an unjust regime (on which latter point, he remained silent, until his death sentence was certain). He himself knew he was giving his life for the truth, that one could not forfeit the universal, spiritual authority of the Church under the Vicar of Christ, and and that he could not sign Henry’s declaration of himself as ‘Head of the Church of England’, without the loss of his soul.

More was no proponent of religious freedom as we now understand that notion. Although the State must leave people free to come to the truth freely, there are obligations on both the State and the individual to the ‘one, true religion’, and this teaching is forcefully reiterated on the document on religious freedom from Vatican II, Dignitatis Humanae, which states:

Religious freedom, in turn, which men demand as necessary to fulfill their duty to worship God, has to do with immunity from coercion in civil society. Therefore it leaves untouched (integram) traditional Catholic doctrine on the moral duty (officio) of men and societies toward the true religion and toward the one Church of Christ.

A society unhinged from the Faith, which is the only thing that provides true transcendent certainty of certain necessary metaphysical and moral principles, will drift inexorably towards dissolution. There has certainly been a development, or at least a nuancing, of doctrine on the extent of this obligation of the State to the Faith since Thomas More’s day (who had no qualms about the arrest and punishment heretics). But our laws must be founded, somehow and someway, on the true revelation of Christ, as they are revealed through the Catholic Church, and there is still room in that same Church’s teaching for the suppression of certain heresies, and heretics, at least those which and who seriously disrupt ‘just public order’.

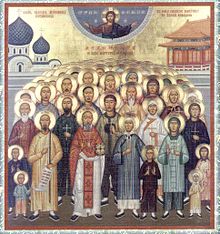

And while we’re on religious freedom, or the lack thereof, today is the feast of the Chinese martyrs, Augustine Zhao Rang and his companions, hundreds of Catholics (along with many Orthodox and Protestants) put to death for their faith, often in brutal ways, from the 17th to 20th centuries. Ironically, the first official martyrdom, of the Dominican priest Father Francisco de Capillas, was on January 15th, 1648, the same year that the Treaty (or, rather, treaties) of Westphalia were signed, which supposedly instantiated the modern era of ‘religious freedom’ under the rather limited principle of cuius regio, eius religio, that the religion of the prince was the religion of the State (with persecution of ‘heretics’, defined by the prince, still broadly allowed). The only real heretic, of course, is one who divides himself from the one, true religion, but, sadly, the pagan emperors saw Catholics as ‘heretics’ disturbing the peace and order of their own realm, and tried to stamp out the religion which they saw as a rival to their own power (see the words of John Paul II on totalitarianism, which I quoted recently on the Martyrs of Rome under Nero and the Roman emperors).

On October 1st, in the Jubilee year 2000, Pope John Paul canonized 119 martyrs by name, but there were hundreds, even thousands, of others, known to God, and such persecution continues. The days are now upon us wherein we too must stand for the truth, and suffer what martyrdom God may send.

But whatever the future holds, keep firmly in mind that, as Thomas More well knew, and on which he wrote as he prepared for his own witness, the good God rewards far, far more than the world could ever persecute.

Holy Martyrs of China, orate pro nobis!