Last year on Palm Sunday we heard the passion from Saint Mark’s Gospel, and next year it will be from Saint Matthew. Each is different in detail from the other, and that holds for this year too, as we listen to Saint Luke’s account. Typically, Luke emphasizes the compassion of Jesus as when he prayed for his executioners: “Father, forgive them, for they know not what they do.” He extends this beneficence even to Pilate and Herod, for after Pilate had sent Jesus to Herod—who ridiculed and humiliated him—the two rulers became friends, “who,” Saint Luke reports, “had been enemies formerly.” And for the women of Jerusalem who wept over him, Jesus has words, if not of consolation then of concern: “Do not weep for me; weep instead for yourselves and for your children.” Supreme among these instances is the dialogue between Jesus and the good thief: “Remember me when you come into your kingdom,” and the response: “Amen, I say to you, today you will be with me in paradise.” This episode has captured the attention of Catholics down the centuries, mainly because of what we would call a surprise ending. But there are more substantial reasons for examining it, for it reveals something about the sacrament of baptism and also about the workings of divine providence.

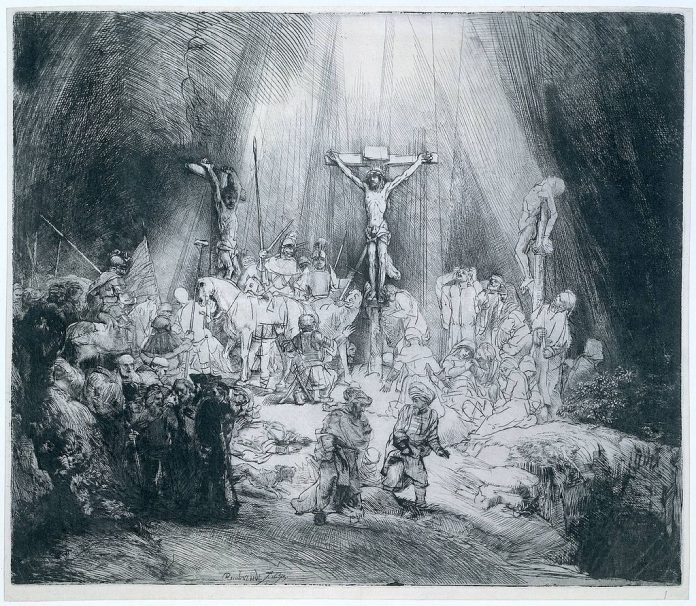

Baptism is a participation in the passion of Jesus: “Do you not know that all of us who have been baptized into Christ Jesus were baptized into his death?”[1] This statement by Saint Paul is instanced in the dramatic scene we are considering, for the faith-filled thief shared, not sacramentally but physically in the passion and death of Jesus: he was there, on the spot! In other words, his prayer joined to his suffering alongside Jesus was his baptism. We know that baptism removes sin and, in an adult, the punishment due to sin. Hence, Dismas—for that is the name tradition has assigned him—died and went to heaven. Fortunate man, to be at the right place, at the right time. And isn’t that the definition of providence, to which this passage directs our attention? When he first heard his sentence, he must have cursed the fate that had brought him to a horrendous death, by crucifixion. And yet we may truly say that it was a blessing in disguise, for it was the means of his eternal salvation. Saint Paul again: “The sufferings of the present time are not worth comparing with the glory that is to be revealed in us.”[2] We see, then, that all the events of what must have been a troubled past were, if not designed by God were certainly used by him to bring Dismas to his glorious end.

The question of evil and especially of moral evil, has always been the strongest argument against the providence, and therefore against the existence, of God. There is, of course, no abstract argument that can adequately respond to the anguish of a profound and personal grief, as I can tell you with decades of priestly ministry behind me; but the history of Dismas suggests that the bad things that people do or experience need not necessarily destroy our faith in God as a loving father. I know of one case, at least, in confirmation of this fact. I was visiting a farmer and his wife after Sunday Mass when I lived in Saskatchewan, in the Canadian prairies. Their son was present, a young man of twenty or so. He was horribly disfigured, one side of his face a mass of twisted and discoloured flesh. When my momentary shock at the sight was noticed, his father told me what had happened. The boy had been building a rocket, and at a crucial moment it had exploded, nearly ending his life and leaving him hideously deformed. When I expressed sympathy, his mother said, “No, it was the best thing that ever happened to him.” Before the accident, he had been a troubled and troublesome teen, a continual source of grief to his parents and his entire family. But afterwards, he changed completely and was somehow transformed into the responsible and caring man I had met.

It seems, then, that it is not misfortune that of itself challenges our trust in God. Rather, it is what use is made of the grief that physical or emotional harm can occasion. There is hardly time here and now to examine the more difficult cases, such as the suffering of innocent children, but our faith in the supreme benefits that have accrued from the death of our supremely innocent Saviour may shed light on this perennial, ultimately unanswerable question. Jesus died for us, and we may say that every innocent person, every child, every foetus, that suffers violence also does so, in one way or another, on our behalf. No doubt, one of the searching questions each one of us will face on judgement day will be, “How was your life, your behaviour affected by the knowledge and even witnessing of innocent suffering?” If nothing else, it must lead to serious reflection on my present situation, on what I owe to others, and on what I can accomplish in the service of God and my fellow man.

[1] Rom 6.3.

[2] Rom 8. 18.