What was your inspiration for A Ceremony of Innocence?

A Ceremony of Innocence is very much a tribute to Graham Green and his book The Quiet American. The big issue he wrote about was the beginning of the American involvement in Vietnam. What I think is the big issue of our time since 9/11 is the spread of a particularly imperialist form of Islam—and how this works itself out in young terrorists, generally home-grown, like the Toronto Eighteen.

How intentional was the Catholic element of the story?

It was intentional. I wanted to write a response to The Quiet American and Greene created a male protagonist who was living with a younger woman. He has an incredible adventure and a rivalry with a younger guy who is very idealistic. I asked: what would this be like from a female perspective?

One of the problems now with writing romances is—what keeps people apart? They do what they want. But if someone had a very moral reason not to marry somebody, that would keep them apart. The Catholic attitude toward divorce can keep people apart, because if they feel strongly enough about marriage they will want to get an annulment. If they don’t get it—that creates conflict.

The novel is not preachy—but at the same time you don’t glorify the fallenness of the characters.

Yes—because it’s not very glorious. If you write about fallen stuff, you write about it as it is—and as it is, it’s fallen. If you are at a cocktail party with glamorous people, and you drink too many cocktails, you are going to throw up. It seems glamorous only when you tell half the story. Telling the whole story can be difficult, but when it comes to something like living in sin, or taking a lot of drugs, you have to tell both sides: why people are doing this in the first place—and why people shouldn’t be doing it, the negative consequences of sin.

How much of the setting is based in reality?

The background is accurate. The apartment really exists; the apartment in The Quiet American also existed. The neighbourhood is the same—I slightly fudged it to make them live in the Frankfurt neighborhood called Bornheim, but actually the principle characters lived just outside it. A lot of the locations are places I remember from my journals, particularly the Frankfurt Hauptbahnhof, which is a building I absolutely loved. There’s a neo-Nazi village in this book—there wasn’t, as far as I knew, a real neo-Nazi village in Germany when I wrote the book—but there is now.

Did you have any reservations writing about Islamic terrorism?

I believe in telling it like it is—or at least telling it like I think it is, which might not be the same thing, although I hope to be rooted in reality. So why can’t we talk about reality? The thought occurred to me that because this book is not all that flattering—because this book even dares to talk about a problem of violence existing in Islam—I could get [attacked]. But I don’t want to live in fear.

Also, when I was writing I was thinking very much of three Muslim girls I know and what they would think when they read the story and how to be fair. And I think it was easy for me to be fair, because I recognize that there is not one thing called “Islam.” There are several different Islams, just as Christianity is divided up. But Islam is undergoing a kind of colonization by one form, which is replacing more pacific and indigenous forms.

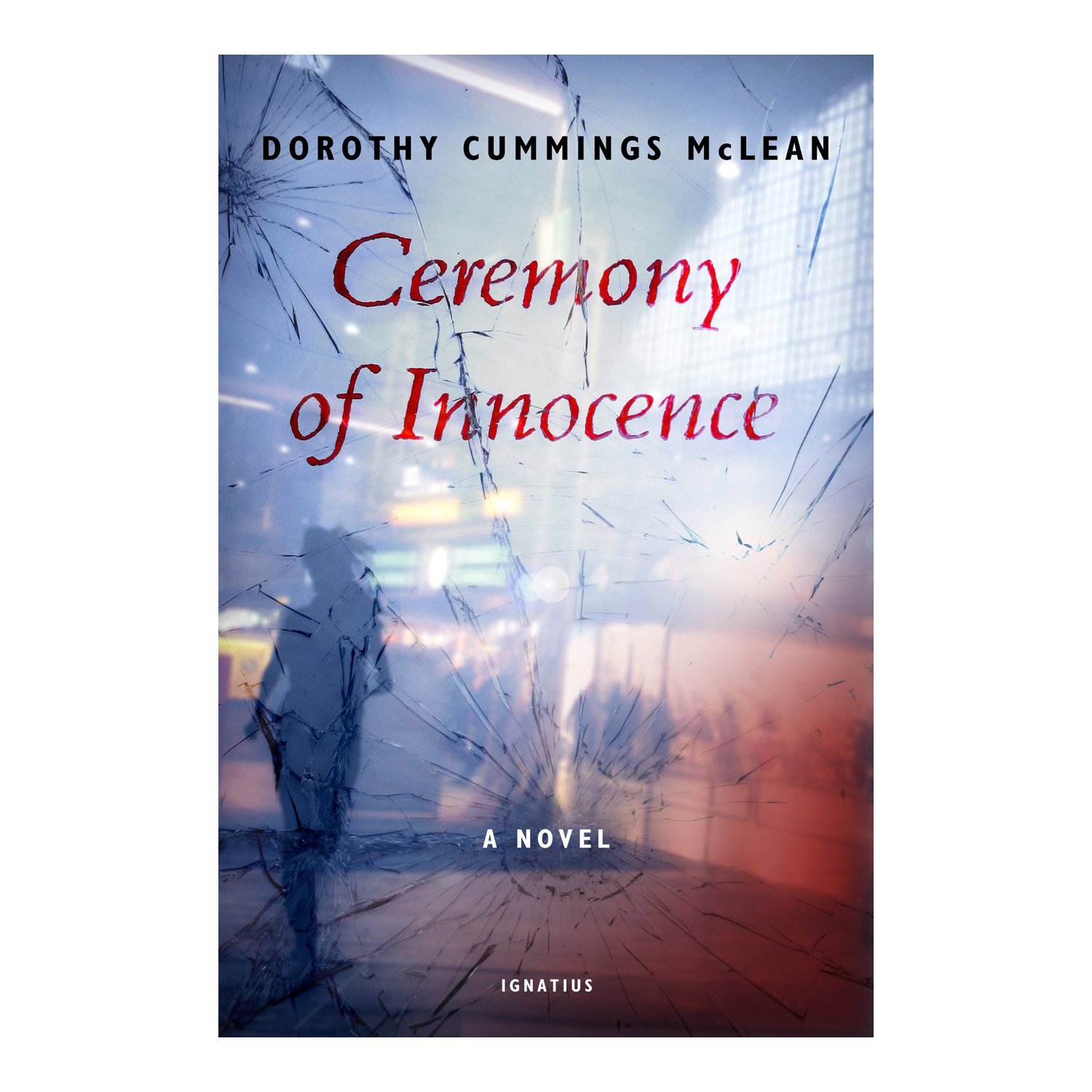

Tell us about the front cover.

The cover is a photograph of the Frankfurt Hauptbahnhof, the main railway station, taken by my friend Johannes. John Herried from Ignatius Press etched Ceremony of Innocence on a glass window and then hit it twice with a hammer. He sent me a photograph of the window before it was imposed on the photograph of the railway station, and I thought it was the coolest thing. To break a window, to break glass, is a violent action. It is done; it is history; and I felt that, having finished the book, whatever happened to me—it was done. It was history. The book is actually in existence. The broken glass is also important for the plot of the book: there is literal shattering. And when glass shatters, there is nothing you can do about it. You can’t put it back together. Or can you? We can’t. But God can do anything.

What is your message to Catholic writers?

Catholics should be writing. We should be writing fiction, we should be writing about the world as we see it. If someone throws a brick through the archdiocesan office window and says, “you are all such-and-suches,” there’s a story in that. Or if people are leaving the parish because they can’t stand the cantor, there’s a story in that. Let’s tell that story. That’s our ordinary life as Catholics. We should be telling stories about the people we know, the stuff we do. And we shouldn’t be afraid of the niche. Book publishing is kind of in trouble, but I don’t think the niche is going to be in trouble.