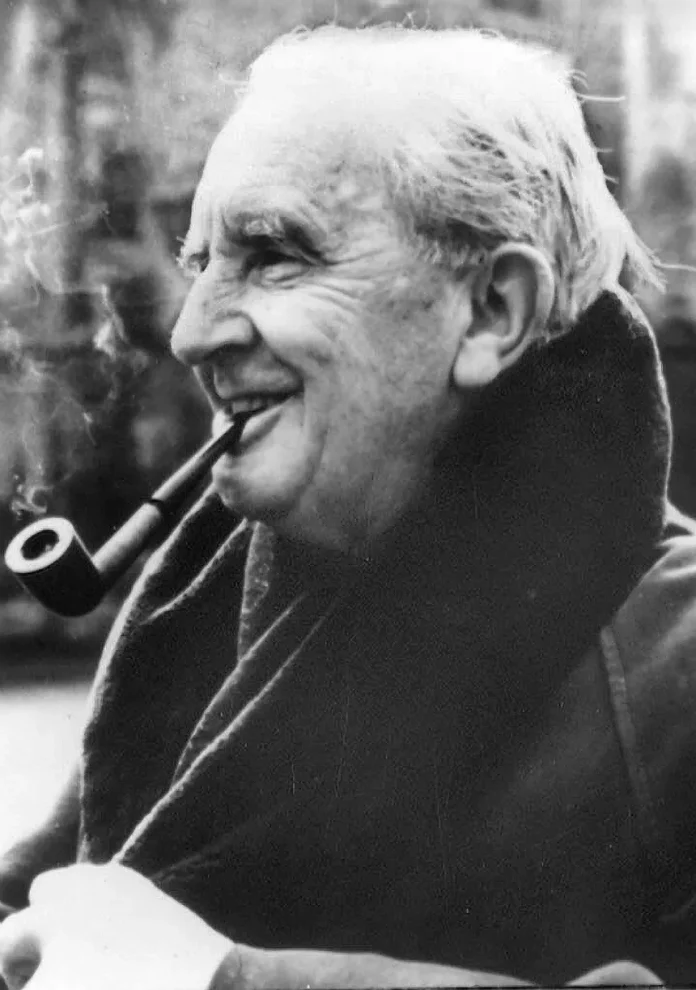

(Here be some thoughts from Kaleb Hammond the connection between J.R.R. Tolkien and the Oratory of Saint Philip Neri, specifically the ‘London Oratory’, in the midst of which Tolkien spent his formative years. We had hoped to post them on January 3rd, Tolkien’s birthday, but, well, the best laid plans and all that. Perhaps providential, since such permits an anecdote into the author’s deep spiritual life: At sixteen, he had fallen precociously in love with Edith Mary Bratt, three years his senior, the emotional turmoil of which was affecting his grades. So his Oratorian priest-mentor, Father Francis, ordered him not to see or write to her until he turned 21. Tolkien obeyed to the letter, and anyone who has ever been smitten by love knows what this must have cost. Edith thought he had lost interest, so became engaged to someone else. Well, a few days after his 21st birthday – on this January 8th, in 1913 – Tolkien got on a train to meet with Edith, and boldly announced his abiding intention to marry her, to which proposal Edith happily agreed, breaking off the prior engagement. Such is love. They were married that March – and much of what unfolded in the years following provided the basis for Tolkien’s great and enduring work. But, first, to Tolkien’s formation by Saint Philip and his community of charity and joy…).

One of the most important influences on J.R.R. Tolkien’s formation as a Catholic was the Oratorian spirituality of St. Philip Neri. Founded in the sixteenth century, the Oratorians follow the rule and imitate the life of St. Philip, living as a community not bound by religious vows but serving the surrounding population (most often in urban areas) and one another through “the threefold ministry given to the Apostles: prayer in common, the administration of the sacraments, and the daily Word of God. The virtues especially cultivated by Oratorians are charity, submission of the individual’s will to the collective mind of the community, and loving to be unknown.”[1] Like St. Philip, called “the third apostle of Rome” after Sts. Peter and Paul due to his service to the poor of the city and “because he did so much to restore the reputation of Rome during a period in which it had become decadent and morally corrupt”,[2] the Oratorians operate schools, visit the sick, accommodate visitors and maintain a liturgical tradition which emphasizes beauty and obedience, thus drawing many closer to Christ.

Tolkien’s first contact with the Oratory came through his mother Mabel who, after taking her two sons to a series of ugly and crowded churches pastored by busy and elderly priests, decided to settle near the Birmingham Oratory, established by St. John Henry Newman as the first Oratory in Britain. There, the Tolkiens discovered a thriving house of younger priests who were passionate and well-educated.[3] With the help of one of the Oratorians, the Spanish-Welsh Fr. Francis Xavier Morgan, Mabel was able to secure Tolkien a place first in the Oratory’s cheaper St. Philip’s Grammar School, then, with the aid of her private tutoring, he was awarded a Foundation Scholarship and enrolled at King Edward’s School in Birmingham.[4]

Following Mabel’s untimely death from diabetes, Fr. Morgan became the legal guardian of the Tolkien boys, raising them in what Tolkien described as “a ‘good Catholic home’ – ‘in excelsis’”, where he became “virtually a junior inmate of the Oratory house, which contained many learned fathers (largely ‘converts’).”[5] Fr. Morgan took the boys on vacations to Lyme Regis[6] while also allowing them to spend time with their relations, despite the anti-Catholic prejudices they held and from which he shielded them.[7] In this way, Fr. Francis became the one from whom, as Tolkien described, he “first learned charity and forgiveness” and corrected the prejudice of contemporary English society against Catholics, including its view of Marian devotion “as an object of wicked worship by the Romanists.”[8]

The marks of Oratorian spirituality proved to be formative throughout Tolkien’s life, and in honor of them, he chose St. Philip Neri as his patron saint. This is confirmed by three interesting facts: the direct confirmation of his daughter Priscilla to Tolkien scholar Dr. Holly Ordway; the writing of his name in Elvish script as “John Ronald Philip Ruel Tolkien”; and the familiar monogram used by Tolkien which includes “the otherwise apparently extraneous spur on the right-hand side of the T upright” indicating the addition of a P to his JRRT initials.[9]

The vocation of the Oratory is characterized by three special emphases: “fervent devotion to God the Holy Spirit, to the Blessed Sacrament, and to the Madonna.”[10] Each of these were also central to Tolkien’s own spiritual life. The Holy Spirit in Middle-earth is called the “Secret Fire” and the “Flame Imperishable,” the divine Person whom Ilúvatar (the Elvish name for the “True God”)[11] sent into the heart of the world at its Creation: “Therefore Ilúvatar gave to their vision Being, and set it amid the Void, and the Secret Fire was sent to burn at the heart of the World; and it was called Eä.”[12] He is also the one whom Gandalf invokes during his spiritual battle against the demonic Balrog on the bridge of Khazad-dûm with his memorable words: “I am a servant of the Secret Fire, wielder of the flame of Anor. You cannot pass.”[13] Tolkien made this connection between the Holy Spirit and the Secret Fire explicit to his friend and assistant, Clyde S. Kilby.[14]

Like his devotion to the Holy Ghost, Tolkien also had a deep love for Christ in the Eucharist. He was a daily communicant[15] and recommended it to his son Michael as the “only cure for sagging [or] fainting faith”;[16] greatly respected and upheld the liturgical Tradition of the Church in a time of upheavals;[17] and penned one of the most beautiful statements of Eucharistic faith in history:

Out of the darkness of my life, so much frustrated, I put before you the one great thing to love on earth: the Blessed Sacrament….. There you will find romance, glory, honour, fidelity, and the true way of all your loves upon earth, and more than that: Death: by the divine paradox, that which ends life, and demands the surrender of all, and yet by the taste (or foretaste) of which alone can what you seek in your earthly relationships (love, faithfulness, joy) be maintained, or take on that complexion of reality, of eternal endurance, which every man’s heart desires.[18]

Tolkien also incorporated this devotion into his legendarium, most notably in the Elven bread called lembas, agreeing with the insight of one reader who connected lembas (Elvish for “waybread”) to the Eucharist as viaticum and “to its feeding the will… and being more potent when fasting, a derivation from the Eucharist.”[19] As Tolkien scholar Bradley Birzer explains, “Indeed, the Elven lembas arguably serves as Tolkien’s most explicit symbol of Christianity in The Lord of the Rings; it is a representation, though pre-Christian, of the Eucharist. For Tolkien, nothing represented a greater gift from God than the actual Body and Blood of Christ.”[20]

Likewise, he also followed the Oratorians in holding a filial love for his spiritual mother, the Blessed Virgin Mary, whom he recognized as “the only unfallen [human] person,”[21] acknowledging the same aforementioned reader’s view that “the invocations of Elbereth, and the character of Galadriel as directly described (or through the words of Gimli and Sam) were clearly related to Catholic devotion to Mary.”[22] He elsewhere stated that “I owe much of this character [Galadriel] to Christian and Catholic teaching and imagination about Mary,”[23] and told his friend, Fr. Robert Murray, SJ, “I think I know exactly what you mean by the order of Grace; and of course by your references to Our Lady, upon which all my own small perception of beauty both in majesty and simplicity is founded.”[24]

Two other attributes are also keys to Oratorian spirituality and were cherished by St. Philip Neri: “loving to be unknown” and a light-hearted spirit which gave St. Philip the title “the apostle of joy.” For Tolkien, “[t]he ennoblement of the ignoble” and “the ennoblement (or sanctification) of the humble” were overarching themes of his works which he found “specially moving.”[25] As he explained, “A moral of the whole… is the obvious one that without the high and noble the simple and vulgar is utterly mean; and without the simple and ordinary the noble and heroic is meaningless.”[26] Despite his impoverished and orphaned upbringing, Tolkien also had what Dr. Ordway describes as a “deep-seated streak of joy and fun”, seen especially in the simple good-nature of the Hobbits: “Both The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings take the characters, and the reader, through darkness, sorrow, and loss, but both stories are also deeply grounded in the simple, joyful life of the Hobbits in the Shire—where both books begin, and end.” He retained this “playful, even silly… joyfulness” into adulthood as a father and Oxford don, delighting, like St. Philip, in playing practical jokes on his friends.[27] In this way, his mother’s choice to raise him in the Oratory proved to be one of many special graces imparted through her to Tolkien.

Footnotes:

[1] Birmingham Oratory, “Vocations”: https://www.birminghamoratory.org.uk/vocations/

[2] Holly Ordway, “What’s in a Name? Tolkien and St. Philip Neri,” at Word on Fire (26 May 2023), at www.wordonfire.org.

[3] Holly Ordway, Tolkien’s Faith (Elk Grove Village, IL: Word on Fire Academic, 2023), chapter four.

[4] Birmingham Oratory, “Tolkien and the Oratory”: https://www.birminghamoratory.org.uk/tolkien-and-the-oratory/

[5] J.R.R. Tolkien; Humphrey Carpenter and Christopher Tolkien (eds), The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien (New York: Houghton Mifflin, 2000), letter 306. Kindle.

[6] Birmingham Oratory, “Tolkien and the Oratory”: https://www.birminghamoratory.org.uk/tolkien-and-the-oratory/

[7] Ordway, “What’s in a Name? Tolkien and St. Philip Neri.”

[8] Tolkien, letter 267.

[9] Ordway, “What’s in a Name? Tolkien and St. Philip Neri.”

[10] Birmingham Oratory: https://www.birminghamoratory.org.uk/vocations/

[11] Tolkien, letters 156, 183.

[12] J.R.R. Tolkien, The Silmarillion, ed. Christopher Tolkien (London: HarperCollins, 2013), 15.

[13] J.R.R. Tolkien, The Lord of the Rings (Mariner Books, 2004), 330. Kindle.

[14] Clyde S. Kilby, Tolkien & The Silmarillion (Wheaton, Illinois: Harold Shaw Publishers, 1976), 59.

[15] George W. Rutler, “To his dying day, Tolkien was a daily communicant,” Catholic Education Resource Center (19 May 2019), https://www.catholiceducation.org.

[16] Tolkien, letter 250.

[17] Tolkien, letter 306.

[18] Tolkien, letter 43.

[19] Tolkien, letter 213.

[20] Bradley J. Birzer, Sanctifying Myth: Understanding Middle-earth (Wilmington, Delaware: ISI Books, 2002), 63.

[21] Tolkien, letters, p. 454.

[22] Tolkien, letter 213.

[23] Tolkien, letter 320.

[24] Tolkien, letter 142.

[25] Tolkien, letters 165 and 181.

[26] Tolkien, letter 131.

[27] Ordway, “What’s in a Name? Tolkien and St. Philip Neri.”