Jean Vanier, the founder of L’Arche, has gone to his eternal reward, at the venerable age of 90. The son of soldier, veteran and former Governor-General George Vanier and his wife Pauline – both of them up for beatification for their holiness of life – Jean founded L’Arche on August 4, 1964 when he took two disabled men out of their institutionalized life – Raphael Simi and Philippe Seux, who may be considered co-founders – into his own home in Trosly-Breuil, France. Jean Vanier dedicated his life in celibacy to his work, and, his witness of life, along with his numerous books, essays and articles, have become a source of hope and inspiration to untold numbers of people.

L’Arche offers those with disabilities a more domestic, community-oriented and overall personal and human life, and grew quickly. There are now 147 L’Arche communities in 37 countries around the world, with waiting lists in all of them. A beautiful and much-needed apostolate of joy and hope. I wonder if there is one in Iceland, boasting of its ‘elimination’ of Down’s syndrome, but am loathe to check. If not, I would urge someone to start one.

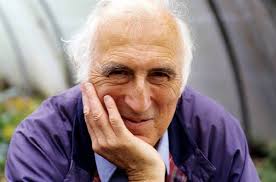

I had the honour of meeting Jean Vanier once, after a talk he gave. A gentle giant of a man, even seated he made an imposing presence, radiating a goodness that comes from a life of patience and self-gift.

As I write that, I am reminded of an anecdote I read in a recent article by Peter Hitchens, on another giant Frenchman, Charles de Gaulle, who had a daughter disabled by Down’s syndrome, upon whom he doted. In Hitchens’ own words:

De Gaulle possessed that great chivalrous virtue of being ready to walk unbowed and defiant in front of the powerful, while being gentle and even submissive to the defenseless and weak. He once became so angry with Churchill that he smashed a chair in his presence to emphasize his rage. Likewise, he defied Franklin Roosevelt over and over again. But he would go home after these battles to sing tender love songs to his daughter Anne, who suffered from Down syndrome. The tiny glimpses we have of this part of his life, obtained from the accidental observations of others, tear at the heart. His concern for Anne was entirely private and not at all feigned. After any long absence from home his first act was to rush up to her room. She died, aged twenty, in his arms. At her funeral, he comforted his wife Yvonne with the words, “Maintenant, elle est comme les autres” (“Now she is like the others”), which must be one of the most moving things said in the whole twentieth century.

Jean Vanier, as far as we know, never flew into such rages, nor did he seem to cavort much with the rich and powerful, but rather spent his entire life with such persons as ‘Anne’, praying, talking, reading, eating, laughing and just ‘being’ with them. And all the ‘core members’ of L’Arche – some unable to ‘do’ much at all in the world’s eyes – will all be ‘comme les autres’ in heaven. May they welcome Jean Vanier home with open arms, saying with Christ, ‘well done, good and faithful servant… truly, I say to you, as you did it to one of the least of my brethren, you did it to me’.