Trite and tautological though the claim may be, permit me to begin by stating the obvious: it is good when good things happen. Good fortune and good luck are called so for a reason, just as are bad fortune and bad luck. Humans disagree about what is and isn’t good, some of them even going so far as to deny the objectivity of goodness altogether. But when it comes to fortune, humans seem to be able to tell the difference between good and bad automatically and without strenuous discernment.

I suspect that good luck is envied more than is a good character. If that is so, it is not because the former is superior, but because it is apprehended with relative ease. Lottery ticket sales seem to prove the point, as millions of humans spend their money regularly to give themselves a remote chance at good luck. You can’t win if you don’t buy a ticket, right? In contrast, the conditions by which a man’s character is deemed good are disputable and, when the notion of good character is not entirely dismissed, disputed. Of course, we ought not envy anyone anything, let alone their good luck; even less should we envy a man his virtue – rather should we learn from and imitate him. Nonetheless, luck is envied often, virtue rarely. Because many people presume to know what it is, there is no controversy in wishing for good luck, or in recognizing it, when we get it, as genuinely beneficial. In contrast, there is much – and oftentimes vehement – disagreement with respect to goodness per se.

Because the desire for good things is natural, it is proper to wish for good fortune rather than bad fortune. We all have luck, both good and bad, and we all rightly prefer to get the good kind more often than not, and much more often than the bad kind. But, as any sensible adult knows, good fortune isn’t enough. All the good luck in the world will not, on its own, make life satisfying, let alone good. It may make it better than it would be otherwise, but better is not necessarily good. We want to live well, not just to have good things happen to us periodically. As much as we wish for and benefit from good luck, the advantageousness of the uncontrolled contingencies of our lives has little, if anything, to do with moral decency. And because virtue is the way to happiness, good luck will not make us happy, either.

Happy people are not people with good luck, any more than lucky people are necessarily happy. Some might be, but not due to their fortune. I’ve not conducted the study – nor do I have any interest in doing so – but I am confident that people who win the lottery are not made happy by winning. Indeed, if I may speculate without a stitch of evidence, I guess that lottery winners are more often less happy for it, not more. If lottery winners begin with sin and vice, as we all do, more money only gives them greater means to foster those sins and vices. Wealth will decidedly not temper avarice, for instance. Quite the contrary. What vicious disposition will be improved through wealth? Not a one, I suspect.

Happiness is not produced by good luck. Instead, happy people are those who bear their luck, good and bad, well. In contrast, however much individual malcontents insist that their luck is catastrophically bad, miserable people are not uniquely unlucky; they bear their misfortune badly, even shamefully. The upshot is that happy people get the most out of the good luck that comes their way, whereas the miserable sort cannot even tell something good has happened, preoccupied as they are with their own misery.

What makes happy people happy is their decency. Because they are virtuous, they grasp that they are not in control of the accidents of circumstance, whether good or bad. They are, however, in control of how they act in the world, how they react to fortune. They understand that they can cultivate their character, and even modify it, if necessary. A person with a good character endures hardship and rejoices in good fortune. His character, not an apparent surplus of good luck, makes him happy. Discussing this issue in the Nicomachean Ethics, Aristotle observes that “something beautiful shines through when one bears many and great misfortunes calmly, not through insensitivity, but through good breeding and greatness of soul.” The moral man’s handling of misfortune is something to behold, and something to imitate.

There are two ways we can bear hardships well, but only one of which is beautiful.

The first is insensitivity: not feeling, not caring, maybe being so resigned to hardship that it barely registers as anything, let alone as something bad. This person’s attitude may be better than the miserable person’s, whose countenance betrays his unrestrained unhappiness, not only when things turn out badly for him, but always, even when they go distinctly well – as they do for everyone some of the time. Expecting, against reason, that life will be easy and endlessly pleasing, the miserable person is perpetually dissatisfied. The insensitive person is not dissatisfied as much as he is defeated. He has no hope, neither for the hereafter nor for the here and now. He accepts misfortune, tolerates failure, and has no expectation that could be frustrated by circumstance, because he has no genuine expectations at all. He bears hardship, but does so unbeautifully. His endurance is ugly.

In contrast, the person with good breeding – who has been well-educated, which is to say, who has been educated to be a moral and virtuous person – bears hardship well and beautifully. He does it without a grimace, maybe even with a joyful smile, recognizing it as misfortune, but not wallowing in it, knowing it does not define or determine his life, not here and now, and certainly not in the hereafter. Indeed, he might, rightly, understand it as an opportunity for further moral cultivation, and, if he is a Christian, for penance. He has hope, knowing he is “on the way” in life, and that, should he but cooperate, things will turn out well, in one way or another. Put differently, he prizes nobility, moral rectitude, preferring such success over whatever chance, bad or good, brings him. He has a great soul – he is magnanimous. He is eminently worthy of imitation.

According to Aristotle, the magnanimous person is the one who is worthy of great things and knows it. It is not just that he knows his worth. A sensible person knows that, too, but lacks greatness. The magnanimous person knows he’s worth a lot. As Josef Pieper puts it, “magnanimity is the expansion of the spirit toward great things; one who expects great things of himself and makes himself worthy of it is magnanimous.” A vain person always thinks he is worth more than he is and a small-souled person, a pusillanimous person, will always believe he is worth less, even if he may be worth much. Only the magnanimous person knows he is great, and, because he knows it, acts in the world accordingly, performing great and noble deeds.

In this context, magnanimity is a worldly virtue, having to do with great accomplishments, actions that somehow improve the world. Alexandre Havard, the greatest living defender of magnanimity, rightly understands magnanimity, paired with humility, as being essential to leadership in all domains. One cannot lead well if not for greatness of soul, if not for a vision of great actions and a recognition that those actions are, indeed, great. Vain people don’t lead; they boss. Pusillanimous people don’t lead; they follow – even if they fall upwards into leadership roles with tragic regularity. Sensible people may lead, but only ever on a small scale. They are virtuous, too, but not great. The magnanimous person is a leader of men.

Worldly magnanimity is noble. It is a virtue worth developing for us all, but, as Aristotle presents it, it is mostly reserved for visionaries and persons with great talent and ambition. I have no quarrel with magnanimity understood in purely worldly terms. But isn’t magnanimity, more properly understood, something all Christians – indeed, all humans – must cultivate, even outside of political, social, or economical circumstance? Can we not be magnanimous in our families, among friends, and even in the mundane moments of everyday life?

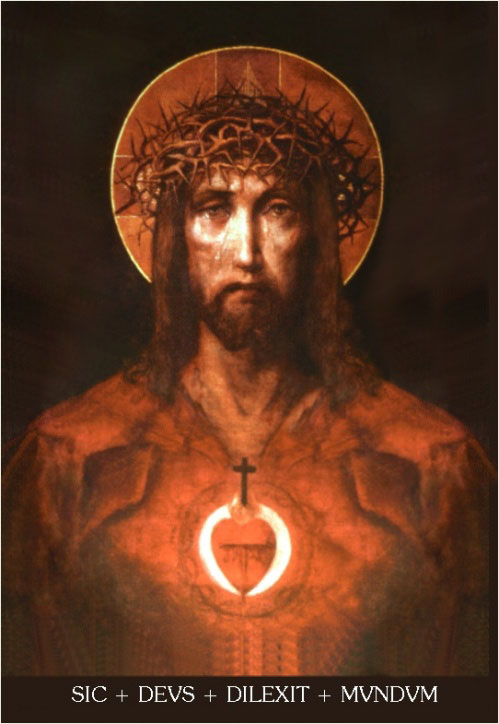

Because they are created in the image of God, humans have dignity: they are good in themselves; they have intrinsic worth. There is no material value that can be ascribed to the human person, body or soul. Thus, every human is worth a lot, immeasurably much. Each one of us is worthy of great things – indeed, what greater things can there be than living in conformity with God’s will, cooperating with His grace, and praising Him? This is a theological and metaphysical truth, even if it is not recognized in the material world where value is cashed out, so to speak. The magnanimous person, thus, knows his God-given worth, and lives accordingly, which is to say, lives the way humans ought to live, virtuously and, above all, faithfully in accordance with divine rule, with the Word.

But so many of us are pusillanimous or vain, small or puffed up. We reject the dignity of human life by denying the creatureliness of human being. Though widespread, nowhere is pusillanimity more evident than in abortion, where some humans are denied their humanity by the false and evil principle that other humans – more powerful ones – have a right to deny that humanity if it is troublesome or inconvenient to them. This is, quite clearly, a total denial of human dignity. Less extreme, but also more pervasive, is the slothful over-indulgence in amusement that is so characteristic of the contemporary age. Preferring mindless movies, stupid online videos, senseless video games, or whatever other sort of petty entertainments fill our ostensibly free time is to deprecate what it means to be a human being. I must think less of humanity than God gave me to think of it in order to waste my time – the time He has given me – in such base pursuits.

Vanity is the flip side of this small-mindedness that rejects human dignity. It is the presumption to be as gods, to not need God. It is the widespread relativism we see today, by which humans decide what is good, what is true, and what is beautiful. It is the insanity that says that men decide who is human and, if they are human, what kind of human they might be, that drugs and booze are more essential to a (putatively) civil society than religious worship, and that casinos may accommodate more gamblers in a lockdown than Churches may the faithful. This vanity is also a kind of pusillanimity, as one can only think he is above God by rejecting Him and his creation. That is to say, the vain person denies human beings’ God-given intrinsic worth. He elevates himself by deprecating God and man at once. The puffed-up puff themselves up precisely because they are so small.

All humans experience misfortune. Most of us have endured more than our fair share in the last year. We probably wish that it had been different, and pray for things to improve imminently. I do. But the misfortune is given; the question is how do we bear it? Are we miserable and pusillanimous? Or are we magnanimous? Do we know our worth, and live accordingly? A pandemic seems to me to be a perfect time to cultivate magnanimity, to work on bearing misfortune well, not without caring or feeling, but beautifully by acknowledging and celebrating our dignity. We might become great-souled if we but recognize our souls are great because God made them so. May no small-souled politician, medical health officer, media talking head, or secularist neighbour ever convince us otherwise.