As I begin this reflection, I am on my way to the Devon coast, having just passed through Bath, set up by the Romans for those seeking the curative properties of the region’s hot springs. This morning, the train departed from the small station at ‘Monks Risborough’, the oldest ‘parish’ in England, founded in 903. This is one over from ‘Princes Risborough’, named after Edward, the Black Prince, a relatively new region, dating from the 14th century. England is steeped in history, even pre-history, and would that all nations could have such quaint and descriptive nomenclature.

Conquered by the pagan Romans, who built walls and roads that still stand to this day, then evangelized by the Christians, Romans, again, from the south, and the Irish from the north-east; then ravaged by the Norsemen Vikings, England in some strange and providential way perfected what she received from this historical cauldron, producing much of what we now know as Western culture. It is from England that we inherit our common tradition of laws, habeas corpus, private property, monarchy, personal rights, parliamentary democracy, manners, mores, language, and even the shaping of the Catholic faith for the western world, in whose milieu we now live, or at least used to.

The undoing of the glory of England began under the tyranny of Henry VIII, who in his youth was one of the most Christian of kings, athletic, poetic, devout, but the bent will that is in us all would brook no opposition in him in his infatuation with the coquettish Anne Boleyn. Alas, in his mad resolve to dissolve his lawful marriage with Catherine of Aragon so he could marry Anne, Henry also dissolved much of what was best in England.

G.K. Chesterton, who is as English as they come, was raised in the faith Henry founded, but dropped into agnosticism in his youth, only discovering the truth and joy of Catholicism in his adulthood. He saw that England lost its head when Henry forced Thomas More, the flower of olde England, to lose his. Chesterton had a great devotion to More, and, upon a visit, we saw that he had set up a ‘martyrs’ chapel’ in his home parish at Beaconsfield, to commemorate the witness of untold number of martyrs who went to their deaths cheerfully under the reign of the Henry and his tragic daughter Elizabeth. The Tudors are lionized in Whig history and modern media: Protestantism saving the day from the stultifying influence of pope-ish Catholicism. But the truth is really the other way around, and the real heroes, as is so often the case, are behind the scenes. To paraphrase one recent author, the history of all that was best in England is really the history of Catholicism in England.

Yet for all that Henry and his successors attempted to erase that history, the dissolution of the monasteries, the stripping of the altars and churches, the erasing of the saints and the razing of the shrines, their memory remains. England is officially Anglican, the church since the time of Henry VIII dutifully subservient to the Crown; but behind this façade, the land is still so Catholic in its buildings, names, history, sites, topography.

To offer but two examples: We visited the hiding place of Saint Edmund Campion at majestic Stonor Manor (a recusant family, who never became Protestant), hidden away in the Chiltern hills. Edmund was a glorious son of England, honoured by Queen Elizabeth the First for his talents. Yet his very intellect led to him to realize the folly of a secularized ‘church’, unhinged from Rome, the Vicar of Christ and the whole Tradition. Like so many others, the totatlitarian State tried to break him on the ‘rack’, mercilessly. Yet, barely able to stand, Edmund made an unassailable defence of the faith against the best Anglican divines before being unjustly condemned to the brutal death of hanging, drawing and quartering.

There are hundreds, even thousands, of others such witnesses, forty of them officially canonized by Paul VI soon after the Second Vatican Council, on October 25, 1970. They all stood for what England once was, and might be again.

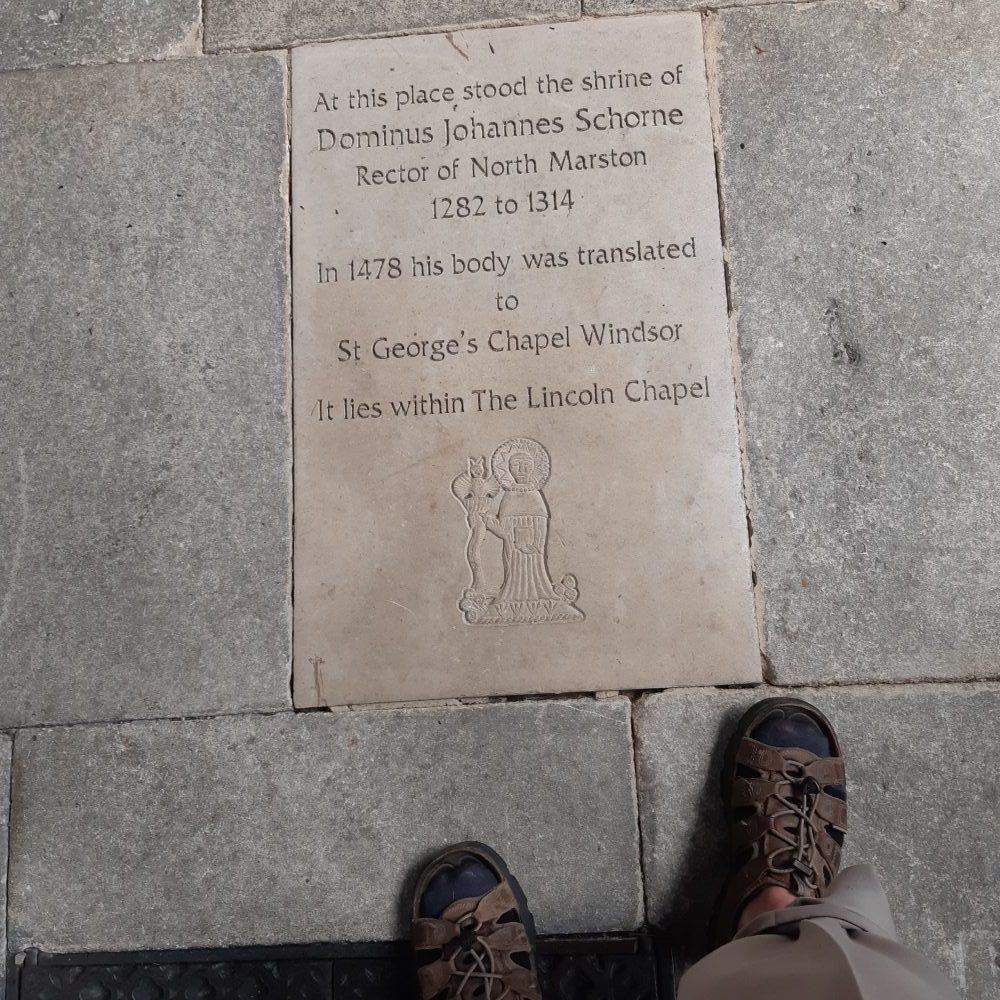

I had a small but significant reminder of England’s past when we visited a small mediaeval church, dedicated to Our Lady of the Assumption, in the town of North Marston, once the third most popular shrine in the country, visited by Henry himself in his more devout days. It was in its parish church that a holy priest, Master John Schorne (+1313), performed all sorts of miracles, before and after death, especially against ailments such as gout, which usually afflicts the foot. Hence, he was said to be able to ‘conjure the devil out of a boot’, which was soon transformed that he had captured the devil in a boot (and how he is often pictured). After that, the devil became ‘jack’ and the boot a ‘box’, and so, as the legend goes, we got the ‘jack in a box’, with the devil jumping out. Scary enough.

I had a small but significant reminder of England’s past when we visited a small mediaeval church, dedicated to Our Lady of the Assumption, in the town of North Marston, once the third most popular shrine in the country, visited by Henry himself in his more devout days. It was in its parish church that a holy priest, Master John Schorne (+1313), performed all sorts of miracles, before and after death, especially against ailments such as gout, which usually afflicts the foot. Hence, he was said to be able to ‘conjure the devil out of a boot’, which was soon transformed that he had captured the devil in a boot (and how he is often pictured). After that, the devil became ‘jack’ and the boot a ‘box’, and so, as the legend goes, we got the ‘jack in a box’, with the devil jumping out. Scary enough.

There is a holy well still there, which still pumps, well, holy water, or at least water that could be holy, and is said to have miraculous properties. We stopped at the local pub for lunch, called, of course, ‘The Pilgrim’. What was once a site of prayer, repentance and intercession, is now but a tourist attraction. If you fill up the well, a little fake devil rises out of a boot.

Yet, for all the occasional kitsch, the land is still dotted with such memories of the age of faith, of all architectural styles, from the solid, castle-esque Norman to the majestic splendour of Westminster Abbey. Of course, most of these are now, again officially, Anglican, devoid of the Blessed Sacrament, but still, they stand.

Sad, that the glory of Catholicism was usurped under Henry’s loyal, heinous, henchman Thomas Cromwell. He, along with Anne Boleyn, and too many others to count more faithful to their King than to their God and His Church, eventually lost their heads to the King’s wrath. A house divided against itself cannot stand, for only the unifying beauty and truth of Catholicism can really bind a nation, a people, into one.

As Chesterton quipped in his Short History of England, “we talk of the dissolution of the monasteries, but what occurred was the dissolution of the whole of the old civilization”.

The ills of modern England as part of that dissolution, and there are many, as with every modern nation, all ultimately stem from her rejection of her Catholic roots, which has continued more or less unabated ever since. We don’t live that far from, again, what Chesterton described as a “governent of torturers rendered ubiquitous by spies”, furthered by the Elizabethand the Puritans under another Cromwell.

We no longer use the rack, for there is no real need. After the latitudinarians, the gradual drift and desuetude of the state-run church into skepticism, and now the age of the agnostics and atheists, we are adrift from any objective moral foundation. Anglicanism was the first Christian ‘denomination’ to permit contraception in 1930, and England now wants to bring in abortion-on-demand, euthanasia, and the recent tragic case of Alfie Evans should be a warning of us all. Others are ‘tortured’ in our stead.

But there are exceptions, stalwart converts, holy priests, monks and nuns, new foundations and apostolates, centres of faith and resistance to the growing tide of secularism, relativism and, creeping in from the edges, a feral paganism.

And there is hope, most of all, in the love of a mother, who always prays for her children: England was called ‘Mary’s Dowry’, a chivalric title signifying that the land belonged in a special way to the Mother of God. The station to which I arrived this morning, not far from the fictional residence of Sherlock Holmes, was called Marylebone, pronounced, as I asked, Maree-lee-bone, an odd name, until one realizes that this is an anglicanization of Marie la Bonne, Mary the Good, one of untold places named after the Mother of God, to whom England and the English were so devoted, and from which sprung the whole notion of chivalry and honour, and why we men should stand up, offer our chairs if need be, when a lady enters a room.

There is a famous shrine to Our Lady in Walsingham, the site of a vision of Mary in the tenth century, as well as of countless miracles. Pope Leo XIII purportedly declared that when England returns to Walsingham, Our Lady will return to England.

Here’s hoping that return happens sooner than later, before the age of what Chesterton called the new barbarians, who roam the streets seeking what they might devour (everyone has advanced alarm systems), an age far worse than the pagans of old, becomes nigh-irreversible, and we see England merrie and good once again

After all, one day, Mary might well return, but asking for her dowry back.