All saints change history, often in ways that are mysterious and opaque, but at times more obviously. Such is Saint Jerome (347 – 420), to whom we may attribute the first truly ‘critical’ version of the Bible, the edito typica, the official, Catholic version of the Holy Word of God. He was a contemporary of Saint Augustine, who was brought to conversion by his own personal struggle with Scripture, but that’s another story.

As a youth, Jerome – Hieronmyous, as he would have been known – seems to have been dissipated, indulging, or at least experimenting in the usual hedonistic student pastimes; but he would always repent, visiting the catacombs, meditating on death, eternity and the possibility of hell. As a classicist, the words of Virgil would haunt him: Horror ubique animos, simul ipsa silentia terrent.

At first, Catholicism repulsed him, but the truth of the Church’s teachings eventually won out his logical mind, and his conversion is dated to about 366, give or take, when he received Baptism, around the age of 20, leaving him many decades to labour in the Lord’s vineyard: And work he did, for after years of intense study, prayer and penance, Pope Saint Damasus I in 382 commissioned Jerome, then his secretary, to translate the New Testament into Latin – then, eventually, the whole Bible, using the best Greek and Hebrew manuscripts. This task became Jerome’s life, a project that both consumed and sanctified him. As he put it in his famous quotation from his commentary on Isaiah: For if, as Paul says, Christ is the power of God and the wisdom of God, and if the man who does not know Scripture does not know the power and wisdom of God, then ignorance of Scripture is ignorance of Christ.

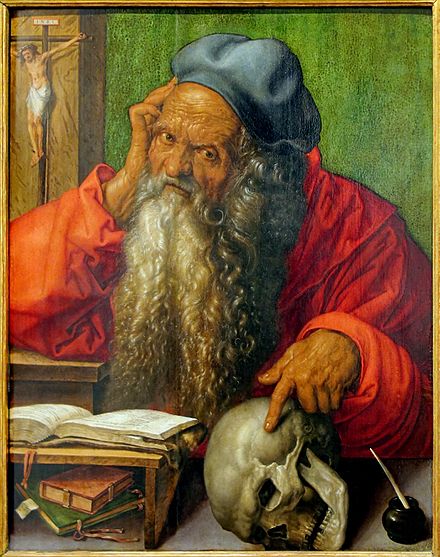

Although Jerome wrote much, commentaries, letters, treatises against heretics, not least the Pelagians who saw no need of God’s grace, it was the Vulgate – so called for it was written in what was becoming the ‘vulgar’ or ‘common’ language, well after the days of Greek in the early Church – that became his magnum opus, for which he is best known. Jerome’s vigorous letters often signify what we would now mean by ‘vulgarity’, and he was polarising, not loathe to use vivid epithets to describe his opponents and their heresies, but all, we may believe, in the spirit of charity and truth. Saint Jerome is often depicted in art holding a stone with which he would beat himself, to quell his rebellious spirit, one may presume; as one Pope put it, were it not for that rock, the disputatious Jerome, perhaps too aware of his own genius and gifts, would not have been canonized.

Whatever the case, the Vulgate was the work of a lifetime. Jerome eventually retreated to a cave in Bethlehem – an underground suite of monastic workrooms – surrounded by his manuscripts and books. He followed a strict regimen, supported by his benefactors, the holy women whom he helped spiritually direct. The ascetic hermit laboured tirelessly with an intensity rarely equaled in the annals of history, dying on this day, September 30th, anno Domini 420, as a septuagenarian.

The Bible that resulted, and as we now know it, really is a Catholic book, as Pope Benedict says in his own reflection. Its origins are divine, the versions and translations that come down to us require careful scholarship, research and Magisterial authority. We owe much indeed to Saint Jerome. Luther would not have a Bible to translate (and truncate and mangle) were it not for Jerome. It was his version, more or less still the same, that the Council of Trent proclaimed in one of its first acts in 1546 as the official Bible which, with a further revision under Popes Paul VI and John Paul II, remains so to this day.

To return to the point, ignorance of Scripture is ignorance of Christ, for it is the very word of God Himself, adumbrating and manifesting the Word, in Whom all truth, all that God willed to reveal for our salvation, is found.