On an intersection in Scotland’s largest city, at Glasgow Cross, the Jesuit priest Saint John Ogilvie, after brutal tortures by the ‘King’s Men’ in 1615 (one of which was keeping him awake for nine days in a row, in mockery of Catholic novenas) was hung, drawn and quartered; the charge brought against him was ‘high treason against His Majesty’, James, the First of England and the Sixth of Scotland, the Protestant son of the Catholic, but (and?) tragic Mary Queen of Scots, herself beheaded by order of her cousin, Elizabeth Tudor, the only daughter of Henry, the VIII.

Father Ogilvie’s crime, if such it be, was to say Mass and hear confessions, clandestinely, for these actions had been punishable since the fiery preaching of the renegade priest John Knox, whose image, Scripture in hand, stands on a pillar overlooking all of Glasgow, fittingly from the necropolis, while there is nary a plaque to the Jesuit, neither on the place of his death (or, as far as I know, of his birth) as I discovered on a little pilgrimage to the site. Just the intersection of Glasgow Cross, fitting, in an ironic way.

I also discovered in my walkabout Glasgow that the original Catholic cathedral of Saint Kentigern, also known as Mungo (the ‘beloved), a magnificent Gothic structure dating from the 12th century, was transferred to, or more accurately usurped by, the new Presbyterians, as they styled themselves, from 1560 or so, and has been used solely for their worship ever since. The Catholics eventually built their own new cathedral, in the face of opposition (guards had to be placed to prevent saboteurs) between the years 1814-1816, when the number of Catholics had increased to 3,000, from a few hundred a decade before. The more modest structure, smaller than many modern parishes, still has its own beauty and majesty, overlooking the Clyde, dedicated to Saint Andrew. So if you are in Glasgow, and ask directions to ‘the cathedral’, be sure to specify.

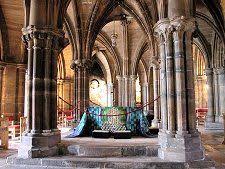

The body of Saint Mungo still lies in the crypt of the old cathedral, presented in a rather non-descript way (Calvinists are not known for their devotion to saints); when I was there the other day, the good saint was surrounded by a lit-up Lego display. One must wonder; but I did say a decade of the Rosary over his tomb, which would not have been allowed in the time of Ogilvie. I am sure all three saints are watching over the ancient city.

Two hundred years before, Catholicism in Scotland was proscribed under pain of death. When Ogilvie was facing his persecutors, Galileo was beginning his battle with the Inquisition, penning a rather remarkable letter on the proper interpretation of Scripture, at which he was more clear than some of his philosophical views. Shakespeare had just published Richard II, and the first Catholic missionaries arrived in Quebec City. The brutal Wars of Religion were just three years away, bringing to the modern world the concept of ‘total war’, where anything, and anyone, was fair game to the mercenary dogs.

And there, in far off Scotland, on a muddy street, a lonely, broken 36 year old priest died on a blood-soaked scaffold before a jeering crowd, offering his life for the salvation of the world, the events of which swirled around him and the salvific Cross for which he offered his life.

Crux stat dum volvitur orbis, the Cross stands, while the world turns. The Carthusiands have it right, indeed.

Saints Andrew, Kentigern and John Ogilvie, orate pro nobis!