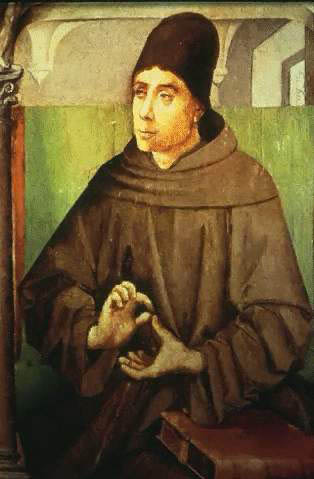

November the 8th is the feast day of the great Franciscan university professor, philosopher and theologian, Blessed John Duns Scotus.

Little is known about his personal life together with the chronology of his writings. We know that he was called by God to embrace the Franciscan charism, joining the Order of the Friars Minor, and received his priestly ordination in 1291. God endowed him with an extraordinary mind., and his characteristic aptitude for speculation secured him the title of Doctor subtilis, “Subtle Doctor”. Duns Scotus dedicated himself to philosophical and theological studies at the illustrious universities of the time, Oxford and Paris.

Following his rigorous intellectual training Friar John Duns Scotus started instructing theology in these two prestigious universities. As did all students – including Thomas Aquinas – he commenced his teaching career by commenting on the Sentences of Peter Lombard. As a matter of fact, Scotus’s principal works are the direct fruit of these lessons, and their titles derive from the names of the places where this great master taught. Thus, we encounter the Ordinatio (in the past it was referred to as the Opus Oxoniense – Oxford). Then comes the Reportatio Cantabrigiensis (Cambridge) followed by the Reportata Parisiensia (Paris). On top of these we can put another important work which are called the Quodlibeta (or Quaestiones quodlibetales). This largely important work is made up of 21 questions on different theological subjects.

Duns Scotus detached himself from Paris due to a rather serious conflict between the King of France, Philip IV (‘le Bel’) and the Fair and Pope Boniface VIII, opting for voluntary exile instead of signing a document which went against the Pope, which the wayward French monarch expected all religious to do. Fully appreciating his faithful obedience to the Bishop of Rome, Pope Benedict XVI immortalized Scotus’s courage and humility with these words during his catechesis on him of July 7, 2010: Dear brothers and sisters, this event invites us to remember how often in the history of the Church believers have met with hostility and even suffered persecution for their fidelity and devotion to Christ, to the Church and to the Pope. We all look with admiration at these Christians who teach us to treasure as a precious good faith in Christ and communion with the Successor of Peter, hence with the universal Church.

Eventually, after the death of Pope Boniface, relations between the King and Pope ameliorated, so that in 1305, this great erudite Franciscan returned back to Paris to lecture on theology as Magister regens (regent master), the modern day term as “Professor”. As time went on, Duns Scotus under obedience settled in Cologne as Professor of the Franciscan Studium of Theology, dying there on this day, November 8, 1305, at the age of 43 years old, leaving behind a systematic work of theology. The Latin text which is still to be found on the ornate sarcophagus explains to us his great Franciscan sense of itinerancy: Scotia me genuit, Scotland bore me, Anglia me suscepit, England received me, Gallia me docuit, France taught me, Colonia me tenet, Cologne holds me.

Due to his holy reputation, his cult was immediately diffused wherever the Franciscan movement went. In March 20, 1993, St John Paul II described Blessed John Duns Scotus as the minstrel of the Incarnate Word and defender of Mary’s Immaculate Conception. This was, in a nutshell, Scotus’ contribution to the history of theology. Scotus wrote:

Was the Blessed Virgin conceived in sin? The answer is no, for as Augustine writes: “When sin is treated, there can be no inclusion of Mary in the discussion.” And Anselm says: “It was fitting that the Virgin should be resplendent with a purity greater than which none under God can be conceived.” Purity here is to be taken in the sense of pure innocence under God, such as was in Christ.

The contrary, however, is commonly asserted on two grounds. First, the dignity of Her Son, who, as universal Redeemer, opened the gates of heaven. But if blessed Mary had not contracted original sin, She would not have needed the Redeemer, nor would He have opened the door for Her because it was never closed. For it is only closed because of sin, above all original sin.

In respect to this first ground, one can argue from the dignity of Her Son qua Redeemer, Reconciler, and Mediator, that She did not contract original sin.

For a most perfect mediator exercises the most perfect mediation possible in regard to some person for whom he mediates. Thus Christ exercised a most perfect act of mediation in regard to some person for whom He was Mediator. In regard to no person did He have a more exalted relationship than to Mary. Such, however, would not have been true had He not preserved Her from original sin.

The proof is threefold: in terms of God to whom He reconciles; in terms of the evil from which He frees; and in terms of the indebtedness of the person whom He reconciles.

First, no one absolutely and perfectly placates anyone about to be offended in any way unless he can avert the offense. For to placate only in view of remitting the offense once committed is not to placate most perfectly. But God does not undergo offense because of some experience in Himself, but only because of sin in the soul of a creature. Hence, Christ does not placate the Trinity most perfectly for the sin to be contracted by the sons of Adam if He does not prevent the Trinity from being offended in someone, and if the soul of some child of Adam does not contract such a sin; and thus it is possible that a child of Adam not have such a sin.

Secondly, a most perfect mediator merits the removal of all punishment from the one whom he reconciles. Original sin, however, is a greater privation than the lack of the vision of God. Hence, if Christ most perfectly reconciles us to God, He merited that this most heavy of punishments be removed from some one person. This would have been His Mother.

Further, Christ is primarily our Redeemer and Reconciler from original sin rather than actual sin, for the need of the Incarnation and suffering of Christ is commonly ascribed to original sin. But He is also commonly assumed to be the perfect Mediator of at least one person, namely, Mary, whom He preserved from actual sin. Logically one should assume that He preserved Her from original sin as well.

Thirdly, a person reconciled is not absolutely indebted to his mediator, unless he receives from that mediator the greatest possible good. But this innocence, namely, preservation from the contracted sin or from the sin to be contracted, is available from the Mediator. Thus, no one would be absolutely indebted to Christ as Mediator unless preserved from original sin. It is a greater good to be preserved from evil than to fall into it and afterwards be freed from it. If Christ merited grace and glory for so many souls, who, for these gifts, are indebted to Christ as Mediator, why should no soul be His debtor for the gift of its innocence? And why, since the blessed Angels are innocent, should there be no human soul in heaven (except the human soul of Christ) who is innocent, that is, never in the state of original sin?

Finally, as a Franciscan and a brother to this greatly erudite and humble man from Scotland, I want to appreciate his phenomenal thought. Scotus developed this principle of haecceitas, the “thisness” which renders every creature “this” particular individual. Like Blessed John Scotus, St Francis held that you and I are known by our innate haecceity even though our uniqueness remains a mystery. Hence, since our haecceitasis is incommunicable, an ultima solitude, you and I have unique value and worth.

We also can say that Scotus’s doctrine of haecceity applied to us, human beings, individually, would seem to invest each of us with a unique value as one singularly willed and loved by God, irrespective of any trait that person shares with others or any contribution he or she might make to society at large. Hence, we can easily conclude that haecceity is our personal gift from God.

Our ultima solitude is to be understood with the possibility of our mutuality, of freely entering into relationship with God, and indeed with each other. God’s desire for a human creature who could love God as fully as possible made us co-beloveds (condilecti) and co-lovers (condiligentes) with Christ, thus beyond God’s incarnation in Christ.

At the very last instance, our ultima solitude helps us to practice our God-given ability to relate to others, to enter into communion with them. According to Scotus, this is translated to love. Fr. Charles Balić, long-time President of the International Scotistic Commission, has written: “The whole of Scotus’s theology is dominated by the notion of love. The characteristic note of this love is its absolute freedom. As love becomes more perfect and intense, freedom becomes more noble and integral both in God and in man. Growth in love gratefully received and freely donated makes one wholly human.

In his response to Prof. Carmela Bianco presentation on Ultima solitude la ‘comunionale incomunicabilità’ della persona in Giovanni Duns Scoto, the former General Minister of the Order of Friar Minors, Fr. Michael Anthony Perry, OFM, inspired by Blessed John Duns Scotus, offers a threefold remedy against the sacred dignity of the human person which nowadays is so cast aside and violated:

The remedy … A first step is to set aside stereotypic generic views of “those others” and then to get to know them as individuals with their own worth and value, their own experiences and perspectives. To see them as different, a gift to be reverenced. The mystery of their uniqueness can never be fully known, yet in friendships and marriages individuals are drawn to explore the deeper mystery of their difference over and over. The haecceitas of each can be woven together in mutuality, in relationship. Getting to know others in their uniqueness and gradually going beyond ourselves and entering into deepening relations with them is the remedy Scotus offers.

The work of all… Beginning to bridge differences and cultivate relationships of healthy mutuality is not easy. It will demand concerted ongoing effort. It will not happen overnight. But it will not happen at all unless breaking down barriers becomes our common cause. This work has to be done by every human being, each taking even the smallest steps day by day. The imperative is clear: spread respect and loving concern, not hatred and violence.

The work of reflection. To inspire and support us in that work, we will need the help of thoughtful leaders who keep before us a better vision, who reflect on what is happening in our world and identify ways to better it, who mine the resources of our human and religious traditions such as biblical injunctions (Mt 5:43-47, 22:36-38; Mk 12:30-31; Lk 6:27-36; Rm 12:11-21) and insights of thinkers such as Scotus, who can re-invigorate us when energies lag or we become forgetful of what we need to do. That is what the world needs now.

Let us make ours the prayer Blessed John Duns Scotus used to pray to God: O Lord, our God…. Teach your servant to show by reason what he holds with faith most certain, that you are the most eminent, the first efficient cause and the last. Amen.

Blessed John Duns Scotus, pray for us!