The recent edition of Living with Christ – yes, you know the one, the disposable missalette (which should be an oxymoron) has on its most recent front cover a photo of a young boy receiving Communion in the hand, standing, looking straight ahead, an image that would have shocked and scandalized Catholics a scant generation ago. What was a sporadic and informal abuse tolerated in many parishes, beginning with the indult of Pope Paul VI soon after the Council, became over time the effective norm, and Covid has now provided quasi-plausible justification for coercing upon one and all reception of the ‘Host in the hand’ only, posing a real crisis of conscience for many.

We should clarify from the outset that, whatever we may think of the practice, reception in the hand is not an intrinsic evil, for the Church could never give an indult for such if it were so. Yet, is it not as ‘good’ as reception on the tongue, and these few words will spell out some reasons thereto. We will then offer some suggestions for what Catholics may do.

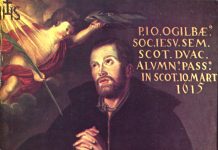

Reception on the tongue, while kneeling (usually at an altar rail or predieu) has been the traditional practice of the Church for centuries, if not millennia. Customs signify something, and there are good reasons why the Church adopted what practices she did. We, in turn, should be very hesitant to change such customs and traditions, just as an a priori principle, even prescinding from what other ‘good reasons’ we in a particular historical epoch may think up.

People will often quote early Church Fathers, with some evidence that the custom in the first centuries was to receive in the hand. Yet we should beware of drawing liturgical and theological conclusions from such scattered writings. This is of a piece with the ‘ressourcement’ of modern theology, of going ‘back to the sources’, and usually, the earlier, the better – to find out what the Church really should believe and do. After all, do we not attain closer to the mind of Christ that way?

Well, not really, for the Church is not a static thing, but a living entity, growing through history towards her final culmination at the end of time. As such, there is a development in both doctrine and practice, as the awareness of the mysteries with which Christ left us, by means of His Apostles, increases. Christ is still with His Church, guiding her through His spirit, counsel, guidance – yes, through human ministers, but real nonetheless.

This guidance of Christ is manifested most clearly and authoritatively through the Magisterium, the Pope and the bishops in union with him. Hence, when we as lay Catholics follow the Church, we listen to the Magisterium first, then the bishop, then the priest. Obedience is a hierarchical virtue in more sense than one – ultimately, the mind of Christ is manifested through His Vicar – and not just the current occupant of the throne, but also all those who came before.

And I will say again, to which we will return, that the ultimate arbiter of our decisions, how and when to act and not to act, is our conscience, where we are ‘alone with God’. But, as per above, that conscience must be formed properly.

The Magisterium has said quite clearly that Catholics have the right to receive Holy Communion on the tongue, while kneeling – semper et ubique. There it be, in clear terms, in the 2004 Redemptionis Sacramentum (cf., esp., #92), reiterated in clear terms in the 2009 clarification from the Congregation of Divine Worship, and once again re-emphasized just recently by the current Head of that same Congregation, Robert Cardinal Sarah.

As far as this author is aware, the Church has never offered any exceptions to this right, and if anyone knows of any, please do pass them along.

We may gather several reasons why reception on the tongue is, at the very least, the preferred option:

This signifies more clearly the reality of the Eucharist, what it ‘really’ is, not ordinary bread, but the Body, Blood, Soul and Divinity of the Second Person of the Blessed Trinity, contained under the ‘species’, or appearance, of bread (and wine). Of course, this is not apparent to our senses (except in miracles), so the Church has adopted in her tradition various customs to maintain our faith, so that we do not, even unwittingly, whittle away our faith, by treating the Eucharist like it is something ‘ordinary’.

This we do for many things in life, even of the secular variety, for human beings live not just on the sensible and material level, but on a transcendent and spiritual one. Hence, we treat sex not as two animals rutting in heat, but as a noble, human loving act, surrounded with romance, tenderness, devotion, fidelity. The same with food: Don’t just gobble, but eat like befits one made in the image of God, for whom a meal is a gift from God, and part of the means to heaven.

What then of the Eucharist? As the ‘Bread of Angels’, we should receive with reverence, even awe, and not handle the species like it is ordinary food.

This is especially the case for children, who may find it more difficult to see ‘past’ the accidents, and whose Faith, as they line up to receive the Eucharist like they are lining up for candy, will almost certainly be diminished.

But this holds even for we adults. After all, the sacraments work ex opere operato – from the very act of their being performed, with their graces fully present. But they also work ex opere operantis, from the work of the one working, dependent upon our devotion. And our devotion, however much we may try, is always in turn dependent on how we act towards any given reality. Our dress, our posture, our disposition, our thoughts, yes, even how we receive.

There is a deep significance to being ‘fed’ the Eucharist by the priest, the alter Christus, who ‘feeds His sheep’, and commanded the first Pope, and the rest of the Apostles, to do likewise. When we receive on the hand, we are ultimately ‘feeding ourselves’, taking the Body and placing it within our own mouths. This is not the same ‘sign’ of being nourished as the Host being placed on our tongues.

We may also consider the problem of particles of the Host being dispersed on the hand – there is a reason why the priest purifies his hands (and the sacred vessels) after handling

Holy Communion. There is no such purification rite for lay recipients, who wander off, perhaps brushing their hands off, or running them through their hair, or nose. In fact, the custom amongst priests – sadly forgotten or ignored amongst many – is to preserve the canonical fingers – the thumb and forefinger, which touch the Host – from touching anything else during Mass. Hence, they hold them together, while using the other three fingers to turn pages and such. This all signifies something very profound, and very real, and it is all more or less lost with Communion in the hand.

The reason given for the change in practice, mandating near-universal Communion-in-the-hand – for a temporary time, it is said – is hygiene. In the current Covidian context, it is ‘safer’, for the priest and other recipients, for people to receive on the hand, to reduce the risk of infection.

I will say at the outset that I am hesitant to invoke hygiene in liturgical change, just on principle. Are we to make our churches ‘clean, safe’ spaces, akin to hospital wards and even surgical rooms? Life is messy and germy – from babies to kissing (which are not unrelated) – and we should just get used to such, as we had, until the fear of Covid and the love of all things antiseptic was planted firmly in our minds and souls.

But let us take the fear as a given: Is it really the case that one has less risk of infection from the hand than the tongue?

The medical consensus is not unified on this, and there is some doubt on either side. Our hands touch many things, including our own faces on average 16 times per hour (and some people, a lot more). We swipe our cell phones – definitely not germ free – about 2,617 times per day (yes, I’m not sure how they got that number, and we all hope we’re nowhere near that!). And how many other things do we touch, scratch or rub? Just watch people put their hands on or near or even in their mouth, or run their hands through their hair – the latter full of bacteria and other germs. Dropping a host lightly onto the tongue of a kneeling communicant seems downright antiseptic in comparison.

Here is what one mother, whose brother is a priest, wrote to me recently, recounting the priests in her brother’s diocese when they met with their Bishop about how they were to administer Communion: I will leave the diocese and participants anonymous.

You will be interested to know that at a priestly meeting…the priests begged him (their Bishop) NOT to require Communion on the Hand. (My brother didn’t need to say anything.) The priests told the Bishop that when they distribute in the hand, they touch every hand. When they distribute on the tongue, they may/might/possibly touch one tongue every six months. (The) Bishop agreed to their request! Amazing.

Now, this is admittedly anecdotal, but it does signify the real-life situation of real-life priests in at least one diocese, perhaps many more. To posit that receiving on the tongue is less hygienic, and more, ahem, infectious, than receiving on the hand, is perhaps the opposite of reality.

Hence, to posit, as more than one diocese has done, that to receive on the hand is an ‘act of charity’, and by implication that receiving on the tongue less charitable or downright uncharitable, seems to make a dubious and, to be honest, judgemental claim. For charity is to ‘will the good of someone’, and we should ask, whatever we say about the physiological good or evil, are we really willing our own – and our children’s – overall and long-term spiritual good by adopting such a practice?

After all, given the principles with which this is being justified, when will this ever return to ‘normal’? When a vaccine is discovered, and foisted upon us? What level of risk is requisite to require reception in the hand, and who’s to say? It seems from what signs there be that what we have now is to be the ‘new normal’ (Oh, how I despise that phrase).

As I wrote recently, it could be reasonably argued that some bishops have gone beyond their authority in outlawing Communion on the tongue, based on controversial medical advice. But what is one to do?

One’s initial take might be to quote the prophet Hosea (6:6), that obedience is better than sacrifice. But, we should ask, obedience to whom, precisely? To the priest? The bishop? The Magisterium? Our conscience? God?

We cannot just go and get the Eucharist for ourselves and distribute as we might see fit – how ironic that would be. Priests also make a promise of obedience to their bishops, and that cannot be taken lightly, nor discounted.

So people in dioceses where there is no option but to receive on the hand seem to be placed in a bit of a bind. As mentioned, one could go along to get along, but this troubles the conscience of many, and, I would not demur.

So there is always resistance and reform – to gather together like-minded people, to write to the bishop and to the priests, respectfully and reasonably, and keep doing so, and do not let up. For those who brought liturgical mayhem upon us did so by their persistence, and we might, in an ironic but also irenic way, bring things back to orthopraxis my similar persistence, in prayer and offering up what we must.

Our thoughts and responses may evolve as this situation unfolds, but, at the very least, we should let our rights be known. Who knows, perhaps that whole notion of the sensus fidelium will win out in the end.

I think that, all else considered, to partake of the Eucharist is better than not – even if one must receive on the hand. Others may demur, and certainly, those who celebrate according to the usus antiquior will not receive except on the tongue, kneeling, in that rite of Mass. As far as I know, they are continuing their Eucharistic ‘fast’, and one wonders what they will do should this continue much longer.

I’m not sure what I would do if faced with this dilemma, but, as I ponder this question, as much as I would like to make a public stand, I would find it even more difficult to give up the Eucharist. Give us this day our daily bread. Perhaps, now that I think of this, one could approach with white gloves, or a white cloth, upon which the priest could place the Host, from which we may consume, the gloves or cloths then being purified – any sign to make reception more solemn and reverent.

I give thanks in being fortunate to live in a diocese where one may receive on the tongue or hand according to one’s proclivities and devotion, even if there be certain conditions (like receiving on the tongue after all those who receive on the hand, presumably so we, the unwashed, don’t ‘contaminate’ them). Oh, well.

However each of us decides, what we don’t want to happen is for Communion on the hand, along with lining up and standing up, as things have been in most places already, are to be the way things are to be, in saecula saeculorum. That is not the law, nor the mind, nor the custom, nor the praxis, of the Church. And we need a band, even a small band, to stand up – or kneel down, as the case may be – for the truth. Deo gratias, for bishops who maintain that option for their flock.

Our God is a God of surprises, as we read in Second Kings this morning, He can act in an instant to bring about His holy and perfect will, even against insuperable odds. So trust, and hope. He will not deny His faithful for long.