The contrast between the disintegrating situation in Britain and Pope Leo IV’s sunny words on migration is a prompt for this brief reflection. We take to heart the Holy Father’s exhortation to welcome and show charity. However, with a possible civil war imminent in England and Ireland, and similar scenarios unfolding across the once-and-sometime civilized world, Leo XIV’s address on the International Day of Migrants, is disconcerting. For all of its hope and rosy-hued optimism, the Holy Father did not address these manifold and metastasizing problems.

To begin, and put this into context, migration in itself is not a good thing, and should be an option of last resort. It’s more a symptom of despair than of hope. Pope Saint John Paul II in his 1981 encyclical Laborem Exercens went so far as to describe emigration as an ‘evil’. Not a moral evil, necessarily, but a ‘physical’ one.

Nevertheless, even if emigration is in some aspects an evil, in certain circumstances it is, as the phrase goes, a necessary evil. Everything should be done-and certainly much is being done to this end–to prevent this material evil from causing greater moral harm; indeed every possible effort should be made to ensure that it may bring benefit to the emigrant’s personal, family and social life, both for the country to which he goes and the country which he leaves. (LE, 23)

One has a natural right to emigrate (but not, we should add, necessarily to immigrate), but one should only do so from dire necessity. The land of our birth has the first hold upon us, and where our primary duty resides. Emigration also divides the extended (and often immediate) family, depriving grandparents, uncles and often even parents of their children, spouses and siblings from each other, and likewise friends. This can be tolerated, but should not be sought, again, barring grave need. Residents of any country should first and foremost strive to stay where God put them and use what talents they’re given to help fix their problems at home:

Above all it (emigration) generally constitutes a loss for the country which is left behind. It is the departure of a person who is also a member of a great community united by history, tradition and culture; and that person must begin life in the midst of another society united by a different culture and very often by a different language. In this case, it is the loss of a subject of work, whose efforts of mind and body could contribute to the common good of his own country, but these efforts, this contribution, are instead offered to another society which in a sense has less right to them than the person’s country of origin. (ibid.)

As Pope John Paul II implies, even if one must seek green(er) pastures, it is requisite that the immigrant contribute to said pastures, and not just consume them, and at the very least not trample them, nor bring along the very pathologies that made their own nation uninhabitable, and a place from which to flee.

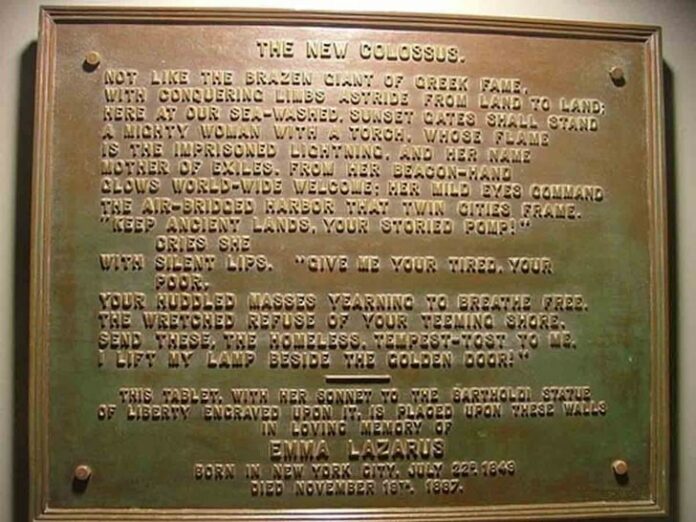

Yes, we should be welcoming the huddled masses and all the rest of it, but the current waves of immigration are not like the Irish and Italians and Germans who flooded American shores in the 18th and early 19th centuries, hoping to hew their bricklaying skills to build the Empire State building or Erie Canal. Those migrants shared the same Christian faith, a similar culture, moral principles, views of marriage and family life, along with a work ethic and skills that contributed to the building up of the nation that had adopted them. They went through due process, were grateful, and they assimilated, while striving to maintain all that was true and good in their own culture way of life. Who doesn’t like Italian food, German beer and Irish music?

To put it mildly, that’s no longer the case. A significant proportion of the current wave of migrants are feral, virile men with little in the way of marketable skills and training, no job prospects and little to contribute in any practical sense. Many of them are sexually and physically aggressive, exacerbated by such inevitable idleness. This is the sharp end of the migrant crisis, and the immediate cause of the protests erupting across Britain and Ireland. One can only wonder what may happen when Sharia law is imposed, at least in certain jurisdictions.

Even with those – we may presume the majority – not so inclined to such violent behaviour, and who just want to live and let live, there is the problem that the religion almost all of them profess does not share that credo. Muslims are not like the Amish. As the very name of their religion implies, all must submit, and all other religions obliterated. Like Voltaire, but for different reasons, they seek to écraser l’infame. If said religions – Christianity and Judaism in particular – cannot be destroyed (and we all know the Church is indestructible) they may be tolerated, but under strict subservient conditions. Dhimmitude may soon be the least worst option.

What makes a culture is primarily its religion, its view of God, His revelation, and our response to His truth. Again, to John Paul II:

A human being is understood in a more complete way when situated within the sphere of culture through language, history, and the position one takes towards the fundamental events of life, such as birth, love, work and death. At the heart of every culture lies the attitude a person takes to the greatest mystery: the mystery of God. Different cultures are basically different ways of facing the question of the meaning of personal existence (Centesimus Annus, 24).

Islam has a very different answer to the ‘meaning of personal existence’ than the Catholic one. No music, and no wine, for starters. And their views of freedom, marriage and the fairer sex do not jibe with what the Church has always held. Alas, our once-thriving Christian culture is in steep decline, and the consequent spiraling death-demography of formerly Christian nations has produced a vacuum, into which other forces almost by physical necessity intrude. Were the Church and her civilization what they once were and are meant to be, we could perhaps absorb a proportion of those of different beliefs and practices, with the hope that they would see the beauty and glory of Christendom, and so be moved to convert.

As it is, the tables are turned. The tsunami of mass migration is exposing, and taking advantage of, our own weakness, accelerating our own slow cultural suicide, which at this point is all-but inevitable, barring some sort of divine intervention. Even America, which has held the line until now, has dropped below replacement level birth rates. One cannot have Christian civilization without Christians, who will, sooner than we think, be in a rather precarious minority.

‘Diversity is our strength’ only if it serves a deeper unity. Accepting millions – the actual numbers are hard to come by, but likely far larger than the official ones – of those who not only don’t share our Christian faith and morals but are openly antagonistic to them, will only lead to further despair and societal dis-integration.

If there is hope here – which is to say, a future good, possible to attain – I would not mind that being clarified. As it is, we can only ask, whose good, and what hope?