In response to Catholic Insight’s post of Carl Sundell’s list of 39 essential questions Catholics should be prepared to answer about our faith, I have been responding to them one-by-one to equip you with clear, concise and (hopefully) well-reasoned answers to help you grow and share your Faith.

None of these answers can be conclusive. They simplify answers and provide a framework to approach these questions. You can find links to previously published articles in this series at the bottom.

6. How would you argue that modern science confirms the universe was created?

In all fairness to this question, modern science cannot confirm the universe was created. This has to do with the philosophical definition of the term “create” as well as the limits of science itself. However, even though modern physical science is not entirely adequate in proving creation, one can infer such from the data taken from observation, and applying philosophical reasoning, which at least makes belief in creation reasonable. Finally, though his argument was not based on “modern science,” but on the limits of reason itself, even St. Thomas Aquinas believed that one could not prove apart from revelation that the universe had a beginning (even if he did believe it was ‘created’ in the sense of dependent upon something else for its existence). There is a lot in this paragraph that needs to be unpacked, so let us take it point by point.

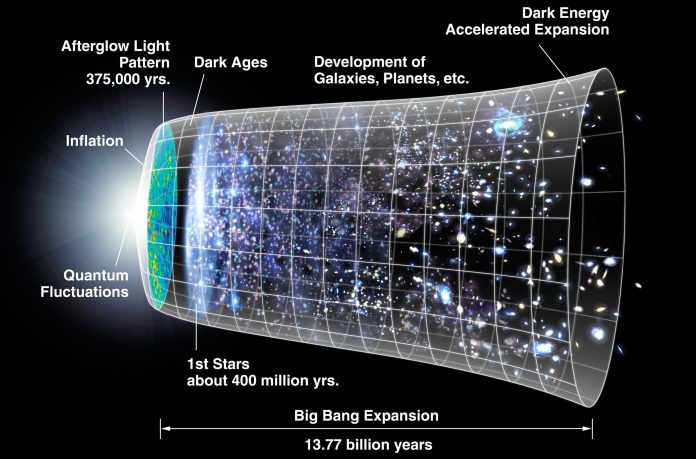

First, the definition of “create” is not how most people use that term Often the Big Bang is cited as the ‘moment of Creation’ as described in Genesis 1. However, the Big Bang would only describe the development and movement of particles that already exist within physical space. This does not necessarily describe Creation the way Genesis or Christianity has historically believed. Creation strictly speaking can only refer to something coming into existence out of nothing. Aristotle’s argument for an Unmoved Mover, which Aquinas adopts as his first way to God’s existence, cannot be used to definitively prove such Creation ex nihilo. Modern scientific explanations can only account for the movement and change of particles within physical space.

Second, the limits of the physical sciences can only measure such movements and changes in the physical universe. However, the creation of the universe would necessarily involve the movement from non-existence to existence of said physical space itself, not just the development or movement of particles within physical space popularly known as “The Big Bang”. Because that movement of particles began with no physical space, it would be immeasurable, and hence would not fall under empirical science.

Third, St. Thomas Aquinas argued in his “On the Eternity of the World,” that one could not come to the conclusion that the universe was not eternal (and hence not ‘created’ in this sense), purely from reason. Aquinas of course believed that the cosmos was created and did have a beginning in time, but based on his Christian faith, not on reason. While the beginning of the cosmos provides some evidence toward answering the question above, it also provides an important apologetic consideration for the Christian. That is, the prudent practice in religious and apologetical conversations consists in determining and clarifying when exactly the gift of faith is required for a person to hold a given truth, and when not.

There may be a misconception that one must passively receive faith for every teaching the Church holds as true, so if one does not have this faith, then one need not accept the teaching. This becomes apparent when certain moral issues arise. Many argue against the Church’s teaching on a moral issue (such as abortion) on the basis that accepting such is a matter of faith, when in reality one can come to know the truth about such a moral teaching from the reason. Inversely, one may see a teaching as a stumbling block because their reason is inadequate to comprehend it completely.

It would be foolish for the Church to require one to comprehend completely the Trinity or to accept this truth apart from faith. Similarly, by recognizing, as Aquinas does, that the creation of the universe can only be known by faith, this takes the burden off of the individual’s reason to comprehend it completely (though any individual is free to use his reason to try to understand the creation of the universe more fully, just as any individual is free to use reason to know more fully the Trinity).

It should also be noted that Aquinas’s position was not monolithic within the Church at the time. Another great theologian and contemporary of Aquinas, St. Bonaventure, wrote his own treatise arguing philosophically for the creation of the universe. Like Aquinas’s writing on the matter, it is relatively concise and understandable.

Finally, while science is limited in proving creation, there is evidence from observation that points toward a Creator, in two philosophical arguments offered by Aquinas. The first of this comes from Aquinas’ third way to God’s existence, the proof from contingency.

One can observe from nature that everything in creation is contingent upon something else (that is, it depends upon some other cause). If everything within the universe is contingent, one could infer that the universe as a whole is contingent. This chain of contingency cannot go on forever, for then there would be nothing in existence at all. This requires a Necessary Being that is the cause of every contingent thing, but is not itself contingent on anything else. While Aquinas does not use the word “Creator,” it would make acceptance of the idea more palatable.

The other piece of evidence comes from the apparent intelligibility that is found in created things. There are controversial theories related to this fact referred to as Intelligent Design and irreducible complexity. In the interest of simplicity and brevity, this article will leave these issues aside, but instead highlight an idea that undergirds both of them called teleology. This is the idea that things in nature are ordered toward an end or purpose, which in Greek is telos. Importantly, it is also the basis for Aquinas’s fifth way to God’s existence as discussed in part one of this series.

One can observe this telos in nature in the same way we can “create” telos in the things we make. We construct, aim and fire an arrow toward a target. The target is the purpose of not only our firing of the arrow but also its shape and material. This same telos is found in natural objects as well. This is the “Design,” which implies the “Intelligent” Something behind it. Regardless of how complex we recognize or determine these observed natural realities to be, it becomes nearly impossible to argue they are not ordered toward an end. If one recognizes the end, then it leads one to a Designer or Creator.

‘Confirm’ may be too strong a word to use when discussing this question with a scientifically-minded person who wants to reconcile faith and reason. However, even in the physical sciences absolute certitude cannot be obtained based on observation alone. One can use reason, along with scientific observation, at least to show that the idea of a Creator is eminently rational, and not opposed to reason. All things in the universe itself points towards that Necessary One’s existence.

Want to catch up on the previous questions? You can find parts one, two, three, four and five (please include link to part five once it is live) here!