If there’s one thing the seemingly ever-lingering ‘pandemic’ has inflicted, it’s a strain on ordinary human interaction.

In November of 2021, when many long-closed museums were opening back up, I had the welcome opportunity to spend a day at the Norman Rockwell Museum in Stockbridge, MA.

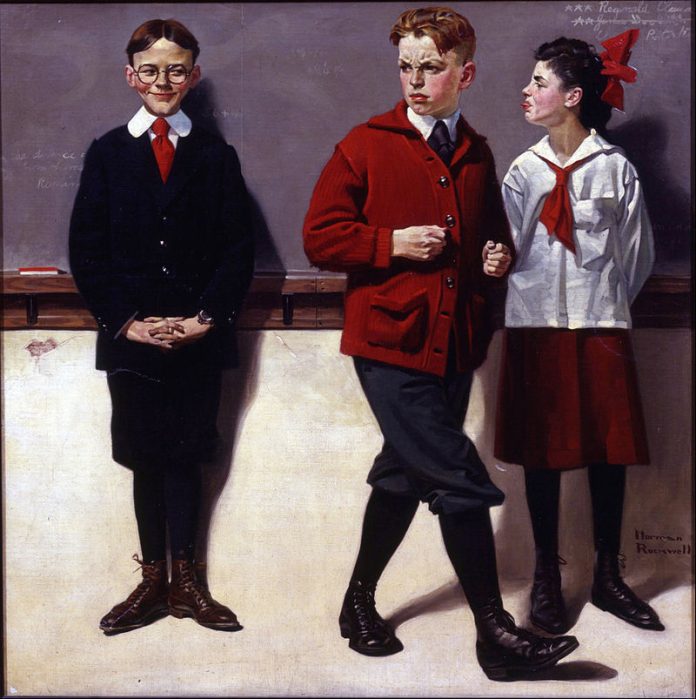

wikipedia.org/public domain

All museum-goers were of course still wearing masks and keeping the required six feet from one another. However, I quickly noticed that the atmosphere in the museum was unlike that of any public setting I had encountered since the start of the pandemic. People laughed out loud, and it seemed unusually easy to strike up a conversation with the person next to you.

While I suspected Rockwell’s work had something to do with the ambience of the galleries that day, it wasn’t until after some further research on the artist and his inspiration that I realized how intrinsic every aspect of his artistic genius was to the joy exuding from my fellow visitors – a group of people likely just as weather-worn by the pandemic years as I.

Norman Rockwell was born in 1894 and died in 1978. Thus, the artist worked through some of the worst the 20th century had to offer. Nevertheless, Rockwell managed to avoid making these catastrophes the center of his art. While the First World War raged overseas, Rockwell painted “cousin Reginald correctly spelling Peloponnesus”. When America and the world sank beneath the weight of the Great Depression, Rockwell chose for his subjects such characters as a fireman, a boy, and a puppy rushing to put out a fire or a very musical-looking, literal barbershop quartet. Such apparent lightheartedness only continued when the world was plunged headlong in the throes of the Second World War, and Rockwell comically depicted a boy carefully (though none too accurately) trying to measure his height.

This is not to say that Rockwell by any means ignored the century’s global crises. In January 1930, he painted the rather relevant People Reading Stock Exchange, while the 1940s saw a handful of war-themed Saturday Evening Post covers such as the famous 1943 Rosie the Riveter cover. However, while Rockwell did acknowledge these worldwide events, acknowledgment (at least in the field of explicit representation) is about as far as he went.

Perhaps this is why some accused Rockwell of advancing a form of escapism – of achieving a facile artistic success by merely sidestepping the crucial issues of his era and selecting instead apparently inconsequential themes for his works. Such accusations, however, tend to surface from a shallow understanding of what Rockwell was seeking to achieve with his art amid the crises of the early 20th century.

Having done a recent deep dive into 17th century Dutch art and being a lifelong fan of Charles Dickens, I couldn’t help but continually notice the apparent influence of these two sources upon Rockwell’s work that day in Stockbridge.

The Dutch masters of the 17th century introduced something entirely new (and even, at times, shocking) to the European art scene. Rather than selecting Christ, the saints, or the aristocracy as their subjects, many of the Dutch artists of the 1600s captured bars, barnyards, and whatever could be called commonplace within their canvases.

Yet what such characters as those of Jan Steen’s The Happy Family (1668) lack in nobility, they certainly make up for in relatability. There’s something refreshingly shocking about seeing a disorganized and even boisterous meal immortalized in a painting. While such paintings may have been considered by some to be irreverent (and not always unjustly) they are more often best characterized as refreshingly human. While few ever handled an eel as a child, there’s something in Judith Leyster’s A Boy and a Girl with a Cat and an Eel (1635) that brings everyone back to a lighthearted childhood moment. It is precisely this power of connection between an artwork and its viewers that so characterizes Rockwell’s works.

One thing I noticed that day at the Norman Rockwell Museum was the number of books on the artists of the Dutch Golden Age that lined the artist’s bookshelf in his preserved studio.

Evidently, the Dutch were a source of real inspiration for Rockwell. Something these artists captured, and which Rockwell picked up on and infused into his work was the dignity of the commonplace. Rockwell, like Vermeer or Hals, had a knack for framing an ordinary moment. However, Rockwell went a step further. While most of these artists’ paintings can draw a laugh, Rockwell’s artworks also strike a heartstring.

Whether it be the grinning faces around a Thanksgiving dinner table or a mother tucking her children into bed, Rockwell’s genre paintings have a heartwarming nature. This is due in large to what might be called the Dickensian nature of the artist’s oeuvre.

While at the museum, I learned that the young Rockwell listened nearly every night to his mother read from Dickens’ novels. The influence is concretely evident in the Dickensian characters, such as Ebenezer Scrooge and Tiny Tim, that feature in some of the artist’s canvases. The goodness that characterizes the genre-like nature of the artist’s works, however, is itself a distinctly Dickensian trait. Dickens localized his novels in some of the most mundane and mucky settings that 19th century England had to offer. Amid stories fraught with injustice, deceit, and even cruelty, Dickens nearly always presented basic acts of human goodness as the solution to human misery. For example, in Great Expectations Pip’s act of kindness to the convict leads to the man’s conversion and further acts of goodness on the part of the convict. It seems it was such natural goodness, apparently unmotivated by anything beyond a near natural impulse, that Rockwell infused into his scenes. An aged cobbler taking the time to fix a damaged doll shoe for a concerned little girl is exactly the kind of wholesomeness Rockwell brought from Dickens’ works to his own.

The Covid-19 pandemic has had an isolating effect on our world. Perhaps we have all fallen somewhat into the habit of perceiving places and even people as potential threats. Now, as the masks have come off, perhaps there’s an opportunity.

Maybe Rockwell can help us to return to our ordinary lives with an even richer outlook than before. It is up to each one of us to be willing to pause and allow ourselves to capture, however momentarily, those lovely scenes of human connection, humorousness or simple, and often subtle, goodness that are daily unfolding about us, but which we often miss for the ‘masks’ we still wear. Such simple beauty can be overshadowed, but people like Rockwell draw those shadows back. Rather than ignore where the pandemic has brought us, we would do well to learn to see the goodness he had such a knack for perceiving – a goodness that is always present, whatever the clouds that haunt our day.