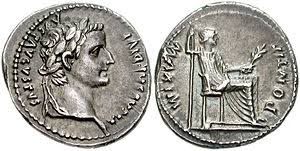

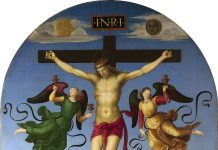

A clever writer[1] once observed that Jesus never made the mistake of qualifying any of his statements: “Sell you possessions, and give the money to the poor, . . .” “If your eye offend you, tear it out, . . .” “Take up your cross and follow me.” One might add the closing line from today’s Gospel, “Give to Caesar the things that are Caesar’s, and to God the things that are God’s.”[2] It sounds simple, but when you unpack it you find that its meaning is far from obvious. For what things are Caesar’s and what are God’s? Admittedly, an initial separation is possible, for the government is in charge of, for example, maintaining roads, national defence, international trade, the courts, and so on, as the Church provides Sunday Mass, religious instruction, and the sacraments for the living and burial for the dead. This division seems clear enough in modern times, when church and state are separate, but such was not the case when Jesus spoke. It was impossible for his contemporaries to conceive of a nation in which religion did not govern all aspects of life. The observance of the Jewish law was not a private matter in first-century Palestine, as the numerous clashes between Jesus and the establishment demonstrate throughout the Gospels. Diet, social conventions, national identity were governed in detail by the Mosaic law as it had developed in the traditions of the elders. The very courts were religious, so that the trial of Jesus was a religious trial; he was accused of blasphemy. (If that were a capital offence today, I wonder how many people would be left standing.) Things were similar with pagan Rome, where the official cult of the gods was regarded as essential to the well-being of the Empire. Hence, when the unthinkable happened, that is, when the imperial city of Rome itself was attacked and sacked by the barbarians in A.D. 410, many people blamed the Christians who, they said, had brought on the tragedy by banning the public cult of pagan gods and goddesses. Saint Augustine was moved to write a refutation of the charge in one of his greatest works, The City of God.

The Middle Ages were no different, in that Catholicism in the West and Orthodoxy in the East were intertwined in the workings of society. The kings wanted to appoint bishops because they were an essential element of the civil service, while the popes wanted men to be ordained who would be pastors of the flock. The result was a bitter struggle that lasted for centuries. Furthermore, the Church’s calendar of festivals and fasts was integrated into the daily life of the people, but also into the sitting of the government, the functioning of the courts, the opening and closing of the school year, and even the planting and harvesting of crops. How could one distinguish what was Caesar’s from what was God’s when often they were identical?

The Reformation may have altered society in many ways, but the role of religion was not reduced. It was not until the revolutions of the eighteenth century that our current understanding of a secular society could take root and spread. Nowadays, religion has little or no role to play in public life. No prayer is recited when parliament convenes or before the speech from the throne. Nor is the practice of religion significant for many—most?—people today. Think of how Christmas is celebrated or how Easter, the greatest feast of the Christian year, is essentially bypassed.

On closer examination, however, the change from a religious to a secular society is more in appearance than in reality. I can justify this at-first-surprising statement by noting the very elements that I listed as Caesar’s—maintaining roads, national defence, international trade, the courts, and so on—are in reality religious in nature for the simple reason that they are all based on morality, that is to say, that in each of them the government is pursuing something good, something that is beneficial to society. Trade, for instance, is supposed to provide citizens with things that are essential for life or that enhance its quality. There are therefore laws enacted to protect the public from dishonest businesses. The same holds for the entire legislation enacted by parliament. It is there to safeguard the social and personal well-being of people and, consequently, of corporations of every sort. National defence, too, is clearly in place to protect the nation from unjust aggression, to save us from tyranny that—in a Hitler, a Stalin, a Mao—so disfigured the preceding century.

How, you may well ask, can such things be religious? They are so because they implicitly recognize that in creating the world, God has placed in it a desire for what is conducive for the flourishing of its separate parts. Plants and animals do so instinctively, but man, in that he possesses intelligence, is required to discover what makes a society successful, and to implement and safeguard it by good government. We can see this in all civilizations, in the past and present, even as we recognize those regions that betray their God-given obligations. One may further note that even the most brutal regimes honour principles that in practice they flout. People are imprisoned because they are “enemies of the state”; concentration camps are explained away as necessary for “re-education”; civil liberties are denied “to maintain public order.” Thus, even the most blatant exercise of political coercion is presented in a way that invokes moral principles whose source ultimately is God. Hence, when Jesus tells us to render to Caesar what is Caesar’s he is reminding us that Caesar’s realm, that is, the public domain, is under God’s direction. We render obedience to Caesar when he—i.e., when government—fulfils its obligations to its citizens.

[1] Robert Lane Fox, Pagans and Christians (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1988).

[2] Matt 22.21.