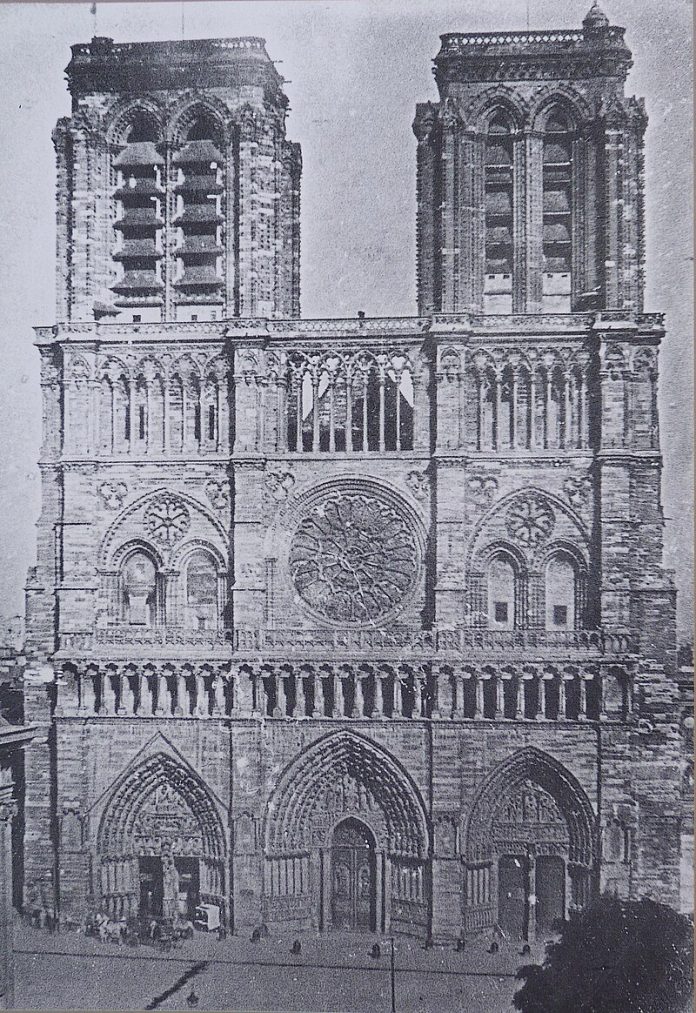

We may rejoice at the re-opening of the Basilica of Notre-Dame, after its partial destruction in the fire on April 15th, 2019. But with some reservation, as befits Catholics in a world where the good will never be fully achieved this side of heaven. The day after the re-dedication, December 9th – this year the Solemnity of the Immaculate Conception in most of the world – was also the day, back in 1905, when France was officially secularized under the anti-Catholic Freemason (and former seminarian) Émile Combes. It was he who instantiated the principle of Laïcité – a complete separation of Church and state. Not only was France no longer a Catholic nation, but a nation with no concern for the supernatural at all. This was a long way from France as ‘the eldest daughter of the Church’ in the glory days of Louis IX. The instantiation of abortion as a constitutional right is only the most recent, brutal reminder of the long, dark shadow of the French revolution which threw off not only her earthly monarch but her heavenly one.

There were Mr. and Mrs. Emmanuel Macron in the front row for the Mass, a practice of which they likely don’t make a habit. Macron is a disciple of Combes, with not much for the Church or her moral law. His glee at aforementioned abortion debacle speaks for itself. We can only hope that spending an hour in the presence of the Real Presence does some good.

And what of the Church in France, which used to hold such sway? Since Combes, she has become something of a toothless lion, with Macron’s pointy polished boots upon her neck. The revolutionaries made the churches of France have the property of state, and Notre Dame was restored as an historical monument, a relic of the past – not so much a sacramental sign of God’s transcendent glory.

And what glory it be. A recent article on the reconstruction of the cathedral by Allan Greenberg offers a glimpse into the making of Notre Dame – not least the flying buttresses allowing the walls of stained glass. He glosses over the controversial crayon vestments and the erratic altar as ‘side issues’. The latter does have a passing resemblance to a granite kitchen island designed by a certain Swedish furniture company. And surely Notre Dame has more fitting chasubles tucked away in some closet somewhere or other? Should not a priest’s vestments signify the armour of God? The image give on December 8th was not so much the Church militant, but the Church milquetoast.

I pose a thought experiment to my students: Would you rather be at Mass in a beautiful church with ugly music, or an ugly church with beautiful music? What we say of music may be said of the various other, rather essential, accoutrements to Liturgy.

I caught a glimpse of the distribution of Holy Communion, the now ubiquitous queuing up, receiving on the hand, the flimsy vestments billowing in the breeze. Everything so ho-hum and humdrum. Nary a paten nor kneeler was in sight. I could only wonder what happened to the altar rails, but they were likely removed decades ago.

Lex orandi, lex credendi – the law of praying is the law of believing. After five decades of such diminished reverence, along with deficient catechesis, one wonders how many in those long lines realize that what is being placed on their hands the very Body, Blood, Soul and Divinity of the Second Person of the Blessed Trinity? Or that the Mass is the sacramental re-presentation of the one, eternal sacrifice of the Son of God on the Cross at Calvary? How many still even realize that this is what the Church believes? Or anything the Church believes, and that Christ revealed for our salvation?

When the Son of Man comes, will He find faith on earth?

Should not a transcendent church be accompanied by a transcendent liturgy?

If, as the secular globalists seem to believe – pardon the paradox – that the great cathedrals are but architectural symbols of a Faith that no longer is, and no longer relevant, then, to paraphrase Flannery O’Connor in a gentler tone, what’s the point? There are far less expensive ways to remember the past than spending a billion euros to restore a mediaeval building.

As someone once put it:

The great…cathedrals, so full of beauty and interest, are now like whales washed up on an alien shore, the faith that built them but a flickering light.

Many such ‘washed-up whales’ have been turned into discos, gyms, apartments and climbing centres. Others are carcasses in a more literal sense – Saint Andrew’s and Walsingham come to mind – left to rack and ruin. There will be more of both kinds of carcasses in the near future, as the Faith continues its retreat from Europe and America.

Deo Gratias, Notre Dame is still a church, the now restored and rebuilt domus Dei where the dim red light signifies God’s presence in the world’s darkness. The high altar received almost no damage, and is now restored; and the irreplaceable rose windows were preserved, a quasi-miracle; the stone walls have been cleansed of their grime and grit, gleaming (even if the sombre darkness from centuries of soot and incense was in its own way evocative).

What was, may be again. Mass will be offered, confessions heard, sins absolved; rosaries recited, candles lit (if they’re allowed, and not those fake electric simulacra); pilgrims and penitents will bow their heads and bend their knees in supplication. Perhaps even the ancient Chant may be sung once again, the old brocaded vestments brought out, and the Holy Sacrifice return to that high altar. Hope! God works through all things, and grace, through Our Lady’s intercession, may even touch the heart of Macron and the myriads who have not received or who have rejected the great gift of Faith. Christ’s eschatological question is rhetorical, not definitive: He is asking each one of us, who do you say that I am?

The cathedrals stand as sacramentals to that Faith, to its solidity, infallibility and salvific power, preserved in the Church, the pillar and bulwark of the Truth. As imperfect, disordered and at times even destructive as things may be, God’s providence is mysteriously at work. We may hope and pray that many find that salvation in Notre Dame, and all the innumerable churches of Christendom, great and small, where God Himself dwells amongst us.

Veni, veni, Emmanuel! +