Saint Thomas, the Apostle, is called ‘Didymus’, the ‘twin’, perhaps, as some surmised, because he looked a lot like Christ. Whether that be true, he’s not like the Saviour in also being called ‘the Doubter’, for, missing on that ‘first day of the week’, he did not believe the other Apostles when they claimed that Christ had been raised from the dead and appeared to them.

But did he? Doubt, that is? This is a term is that needs a bit of refining (used in a rather ambiguous manner, even in erudite and orthodox circles): To ‘doubt’, in the theological sense, requires that one first have the truth revealed to them from a supernatural source, that they have accepted that truth with divine and supernatural faith, and then have allowed that faith to wither, to some degree. In the strict sense, ‘doubt’ is a sin against the virtue of faith. As the Catechism puts it:

Voluntary doubt about the faith disregards or refuses to hold as true what God has revealed and the Church proposes for belief. Involuntary doubt refers to hesitation in believing, difficulty in overcoming objections connected with the faith, or also anxiety aroused by its obscurity. If deliberately cultivated doubt can lead to spiritual blindness. (#2088)

This follows from the nature of supernatural faith itself, which a future Thomas, d’Aquino, would define as an act of the intellect assenting to the divine truth by command of the will moved by God through grace (cf., CCC, #155; ST, II-II, q.2, a.9).

The last phrase of that definition is key here: We believe primarily not because it ‘makes sense’ to us, but rather because of the authority of the One Who reveals, God Himself. We can and should doubt in natural faith, wherein the formal object of our belief – that is, the authority in which we put our trust – is some fallible human, or consensus, as in, say, anthropogenic carbon-induced climate change or the transmission rates of a hidden virus, or, in Thomas’ case, his fellow apostles.

But to doubt God, Who can neither deceive nor be deceived? Cardinal Newman, who thought much of the nature of faith in his own spiritual journey, wrote that ten thousand difficulties do not make one doubt. We can question, ponder, analyze, mull over, struggle with any number of the articles of faith, especially the ‘hard’ cases of salvific suffering, moral evil, salvation, the reality and eternity of hell and heaven, the substantial presence of Christ in the Eucharist, and so on, but we cannot, or at least should not, doubt any of these truths.

Thomas refused to believe his fellow Apostles when they declared that they had seen the living Christ, still with the marks of His brutal torture and death by crucifixion. The Apostles, for all their authority, are not Christ, and so Thomas wanted empirical proof, to put his hands and fingers in the very wounds.

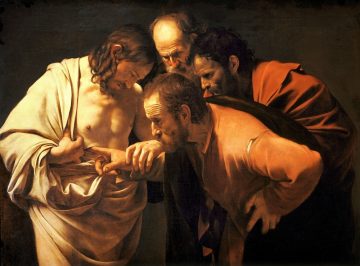

As we know, Christ does appear to Thomas eight days later, on the Octave of His Resurrection, and offers to have him so put his hand in his side and his fingers in the mark of the nails, declaring to him, as some translations have it: Doubt no longer but believe. Or, in the original Greek: me ginou apistos, alla pistos, which other translations render, more literally, as Do not be unbelieving, but believing.

Thomas did not so much reject, as at first refuse to accept, the fullness of faith. The appearance of the Risen Christ was the beginning of this perfect faith of the Apostle in the resurrection, the defining hallmark and principle of our Christian belief.

Thomas responds to Christ’s invitation by making that simple declaration of faith echoed by Christians throughout the ages: My Lord and My God, and there is a pious tradition that we repeat those words sotto voce as we adore the sacred Host and Blood as they are elevated by the priest after the consecration at Mass.

Contrary to what Christ said to Mary Magdalene, Noli me tangere, He offered his wounds to Thomas, even if there is no evidence the Apostle actually touched Christ – pace, Caravaggio’s imaginative artistic skill – and really there was no need for him to do so, for faith is a supernatural gift, bestowed on us by God, and not the fruit of some scientific or empirical verification. Sure enough, such so-called motiva credibilitatis, motives of credibility – miracles, visions, prophecies, proofs and so on, including a crucified man rising once from the dead – can lead us to faith, or help bolster our faith, but they cannot be faith itself. (cf., CCC, #156)

But as Blaise Pascal wrote – and, yes, we must take him with a grain of Gallic salt, tinged as he was with Jansenism – for those with faith, no proofs are necessary; and for those without faith, no proofs will suffice.

A case in point is the infamous Emile Zola, an anti-Christian atheist in France in the late nineteenth century, who witnessed the cure of a young woman ravaged by lupus at the then-new sanctuary of Lourdes; her face, as he himself described, was a suppurating mass of decaying flesh and blood. When she came out of the spring, the woman was completely cured, a biblical-esque miracle. Yet Zola refused to believe, saying there must have been some other cause than God’s divine efficacy.

Yes, one might even explain away a formerly dead-man walking around with the scars of crucifixion. There could, in theory, or at least in attempt, be some ‘scientific’ explanation, and a person of Zola’s materialistic and atheistic a priori dispositions, who fill our universities, schools and media, would strive to find one, rather than actually, God forbid, submit to grace, assent to faith, and believe.

But Thomas did, to his credit, even if Christ praised more fully the merit of those who have not seen, and yet believe.

In the end, faith is not just an intellectual act, but rather a fruit of our relationship with Jesus Christ, the mediator Who brings Man to God. Our faith in Him and His word should be unfailing, for it relies ultimately not on our power, our fallible, limited minds, but the grace and authority of God Himself.

As Saint Gregory the Great put it in today’s Office:

Do you really believe that it was by chance that this chosen disciple was absent, then came and heard, heard and doubted, doubted and touched, touched and believed? It was not by chance but in God’s providence. In a marvellous way God’s mercy arranged that the disbelieving disciple, in touching the wounds of his master’s body, should heal our wounds of disbelief. The disbelief of Thomas has done more for our faith than the faith of the other disciples. As he touches Christ and is won over to belief, every doubt is cast aside and our faith is strengthened. So the disciple who doubted, then felt Christ’s wounds, becomes a witness to the reality of the resurrection.

The faith of Thomas the Apostle would soon resound to the ‘ends of the earth’, for by our tradition it was he who brought to faith farther than all the other Apostles, to Asia, India, where he by tradition met his martyrdom, and where he has been venerated since time immemorial…Their voice goes out through all the earth, their word to the end of the world.

Be no longer faithless, but faithful. For a life without faith is a life without hope, without joy, really, a life without life.

Saint Thomas the Apostle, ora pro nobis!