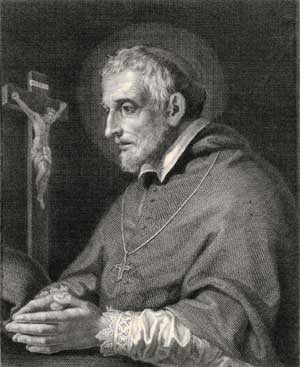

Saint Philip Neri, the founder of the Oratorians and the ‘second Apostle’ of Rome, recommended reading books beginning with ‘S’, that is, lives of the saints, so that we may imitate at least some degree of their virtues. He himself wanted all of his own spiritual sons to achieve sanctity, but in as hidden a way as possible. Amare nesciri, he would say, ‘love to be unknown’.

This motto would be taken to heart by the Oratorian saint – still a ‘blessed’ – we celebrate today, John Juvenal Ancina (his parents added the middle name of the 4th century bishop and confessor Juvenal in thanksgiving for a miraculous cure of their son).

Juvenal, as he was known, was an immensely gifted man who could really have become anything he set his mind to: Of the highest intellectual aptitude, he studied at Padua, Mondovi and Turin, graduating in philosophy and medicine, and worked as a physician for some years. He was also a gifted orator, poet, musician and composer. Yet his favourite occupation was to be hidden with God in prayer, doing menial tasks, polishing candlesticks and cleaning the sacristy.

Juvenal was friends and acquaintances with popes, bishops and princes, corresponding with such influential figures as Francis de Sales and Robert Bellarmine.

It was around 1575 that Juvenal met Philip Neri, who had founded his incipient Oratory that same year, and, influenced by Philip’s charisma and sanctity, he soon joined the group of zealous priests, dedicated to steering the new humanism in a Christian direction, using all the arts and sciences for the glory of God and the conversion of souls.

Juvenal was happy here, fulfilling his priestly work, but his gifts could not be hidden long, and in 1602, at the insistence of Pope Clement VIII, he was appointed Bishop of Saluzzo in northwestern Italy.

As would be expected, Juvenal proved a model bishop, with a solicitous care for the poor, for preaching, and for utter dedication to his people, Catholic or not (once resigned to becoming a bishop, Juvenal himself requested Saluzzo, as it was one of the least Catholic dioceses, so he could work on converting heretics).

But there were also renegade Catholics. One such, a wayward monk whom Juvenal reproved for visiting a convent with lustful intent, poisoned the bishop with a glass of wine he offered, falsely, as a sign of reconciliation.

Juvenal soon suffered its effects, whispering ‘Oh, what poison! What terrible poison this is!’, which, coming from a man used to penance and suffering (he was found with a hairshirt under his cassock, and slept only about 5 hours per night), meant more than what we ourselves might mean by those words.

The good bishop made his confession, received the last rites, and, commending his soul to Jesus and Mary – his last words were ‘Jesus, sweet Jesus, with Mary, give peace to my soul!’ – Juvenal died peacefully in his 58th year, far too young. That was the age at which the future Karol Wojtyla was elected Pope, and we can only imagine what good John Juvenal Ancina might have accomplished, had he been given that extra quarter century.

But God has His mysterious ways, often brought about indirectly through Man’s own evil, something we should keep in mind through this present crisis.

And He wanted Juvenal, like an even more youthful Ste. Thérèse, to do more good in heaven.

Our bishops and priests, and we along with them, would do well to imbibe a drop from Juvenal’s life-giving chalice, and pick up a few more books beginning with S.

Blessed Juvenal Ancina, ora pro nobis!