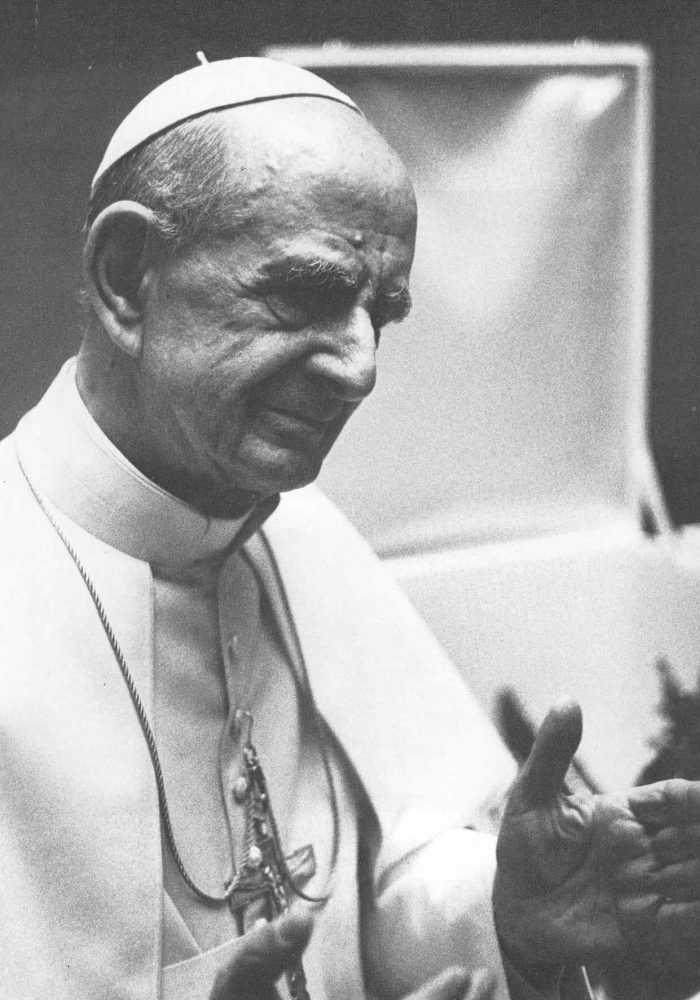

The controversial Pope Saint Paul VI is commemorated on May 29th, the day of his ordination to the priesthood in 1920 – this marking the hundredth anniversary. He was the second-last Italian Pope, a run of pontiffs from the nation that had last 455 years, which may seem odd for a Church that claims universality. But such are the ways of providence, and after the brief 33-day reign of John Paul I, Pope Saint John Paul II began what seems to be a run of non-Italians – even though Francis – Jorge Bergoglio – is an Italian by blood.

Paul VI, like almost the Popes before him in the modern era, was of the ‘nobility’, and destined for some high office or other in the Church, trained in diplomacy and, as they say, Romanitas. We may wonder at some of his decisions in striving to maintain peace, and evangelize an ever-more secular world. His decision to continue the Council called by Pope – also saint – John XXIII was momentous, but more so was his reform of the ancient liturgy, especially the Holy Mass, giving Annibale Cardinal Bugnini a lot of free reign to construct the Novus Ordo, promulgated in its editio typica Latin version in 1969 – one almost never said – and the English and other vernaculars beginning in 1974 – always said, and often not with what reverence one might expect from the most sacred of sacrifices.

As his addresses of that fateful year of 1969 attest, Paul VI had high and optimistic hopes for the ‘new Mass’ – more strictly, the new use (usus) of celebrating Mass – and his decrees more or less forbade the celebration of the usus antiquior, as decreed by the Council of Trent (even if that use was never legally proscribed, and, Deo gratias, is now permitted universally by Pope Benedict’s 2007 Apostolic Letter Summorum Pontificum). hopes that seem to have hit the hard wall of reality. Lex orandi, lex credendi, lex agendi – the law of praying is the law of believing is the law of acting. Or we act and believe as we pray. One has to wonder about Paul VI, who seems to have been a good and pious man, dedicated to his religion, who loved the Mass and beauty and liturgy, and especially to the Blessed Mother, on whom he wrote three letters. How much did he see what was going on around him, and the liturgical and moral chaos that was a hallmark of the seventies?

He seems to have seen something of this, for the last encyclical he wrote, after much prayer and reflection – some say dithering and hesitancy – on the feast of Saint James the greater, July 25th, 1968, was one of the most prophetic of the 20th century, dividing the Church ever since: Humane Vitae, which taught the beauty, integrity and harmony of the marital union, that there was a nexus indissolubilis, an indissoluble bond, between the unitive and procreative significations of this most intimate of human acts. To try to divide this union by any means – that is, any sort of ‘contraceptive’ act – was gravely sinful, and would lead to all sorts of deleterious consequences, which we now all around us.

The world by and large rejected Paul VI’s message, and perhaps it was because of the barrage of unrelenting criticism that he did not write another encyclical, although he reigned for a full decade more, before his death, broken and worn out, on August 6th, the feast of the Transfiguration, 1978. Maybe he thought that Humanae Vitae said what he had to say, and that its teaching was really the linchpin that held everything else together. As marriage and family go, so go society: To hell, or to heaven.

The Church canonizes her members not because they are perfect, or because they make all the right decisions, but because, in the end, they held to the truth, suffered for its sake, and witnessed thereto. Could Paul VI have done more, or done things differently? Yes, and we could say the same for all the saints – and the saints would say it even more of themselves. Who knows? Maybe it was his intercession that helped get the usus antiquior back into our churches, and we may pray that we return ever-more to liturgical and moral sanity – for you can’t have one, without the other.