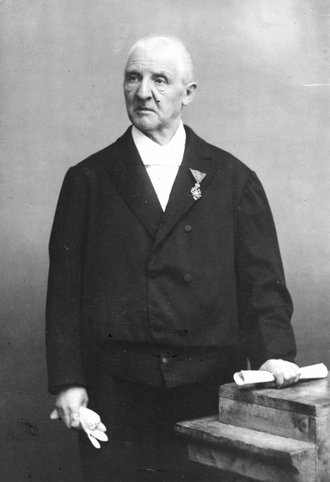

Faith and music are forever intertwined in Western art music. Many, if not most, of the leading classical composers were people of faith. Anton Bruckner (1824–1896), a devout Roman Catholic, was primarily a composer of symphonies and sacred music. He was described by his pupil Franz Schalk as, “…a believer without compare. He believed with an intensity that bordered on the miraculous.”[i] Bruckner’s deep faith informed and shaped his compositional process, whether an elaborate Mass setting or a monolithic symphony, his faith was the foundation upon which everything else stood.

From the time of his childhood until his death at the age of 72, Bruckner was always close to the Church. His father was the parish organist in their rural village of Ansfelden, Austria, and the young Anton spent several years living in the nearby Abbey of St. Florian as a chorister. He would later return to the monastery as an adult to teach, and in many ways, this was his spiritual home. He would go on to become the titular organist of the cathedral in Linz, where he wrote several of his sacred works, including nearly three dozen motets and the three mature Mass settings. While Bruckner may be best known for his symphonies, even these are certainly expressions of his faith. The ninth symphony, left unfinished when he died, is dedicated “to my beloved God.”

German musicologist Friedrich Blume (1893–1975) stated of Bruckner, “there is no other composer in the 19th century who was rooted so firmly in a lived, heart-deep devoutness, to whom prayer, confession, sacrament and profession were vital elements to such a high degree.”[ii] Bruckner was known to keep record of his daily prayers in a pocket calendar, of which 22 such calendars have been preserved. He used a system of scrawled symbols and initials to keep track of the number of prayers said within each day and counted his prayers in this manner from February 1882 until his death on October 11th, 1896.[iii] It is also thought that Bruckner experienced religious visions. He once remarked to Arthur Nikisch about such visions, from which Bruckner found the inspiration for many of his works. His pupil Friedrich Eckstein recalled how, “He occasionally spoke of the shudders evoked in him by the Good Friday liturgy and of the mystery of the night from Maundy Thursday to Good Friday, whereby his facial features…took on a totally changed expression of fear and aching rapture.”[iv] He was known to pray before improvising at the organ during Mass, before composing, and would even stop in the middle of teaching a lecture to pray.

A young writer and critic named Max Graf once sat in on one of Bruckner’s classes, and recalled that, “during the lecture, the Angelus bells rang, and Bruckner immediately knelt down to pray. I have never seen anyone pray as Bruckner did. He seemed to be transfigured, illuminated from within. His old peasant face, with the countless wrinkles covering it like furrows in a field, became the face of a priest. Like many peasants in the Alpine provinces of Austria… Bruckner had a Roman profile, and when he prayed, or when he played fragments of a new symphony at the piano (that was a prayer, too), his face took on a magnificence that was reminiscent of the busts of old Roman emperors. But his expression may best be compared with that of the Apostles in the paintings of Giotto. “[v] Likewise, as many of his students have relayed, he would suddenly seem to disappear during a private lesson to pray, especially if nearby church bells were ringing for the Angelus.[vi] It is impossible to believe that this man’s intense religiosity could not have influenced his music.

Bruckner’s faith inevitably informed his composition. His interest in emulating Renaissance polyphony (as seen in Mass No. 2 in E Minor, although in his own chromatic language), as well as plainsong and the Church modes speak to his immersion and familiarity with sacred music, but also someone who actively engaged with the great musical patrimony of the Roman Catholic Church. His aforementioned Te Deum stands as his greatest choral work. The composer considered his Te Deum to be the pride of his life,[vii] and it is dedicated “Ad Maiorem Dei Gloriam,” “for the greater glory of God.”

Written in five movements, the piece lasts approximately 24 minutes, and is scored for four soloist, mixed choir, full orchestra, and organ ad libitum. It begins with a colossal opening, with the strings and organ playing open fifths over a pedal point. The chorus soon enters, and by the end of the second phrase, the music has pivoted, and, in typical Bruckner fashion, the tonality travels through many keys in the course of the work. With almost Baroque-like dynamic shifts and colourful harmonies, the Te Deum is a glorious manifestation of Bruckner’s deep faith.

Anton Bruckner was indeed a man of great faith. Immersed in the music of the Church from the time of his youth, he went on to be the 19th century’s greatest composers of both symphonic and scared music. He was a man of prayer, a man of God, and his output is stamped with the indelible mark of his faith. He once said of himself, “They want me to compose in a different way; I could, but I must not. Out of thousands, God gave talent to me. One day, I shall have to give an account of myself. How would the Father in Heaven judge me if I followed others and not Him?”[viii] Bruckner’s faith informed and shaped his composition. He was God’s musician, the master builder of cathedrals in sound.

Recommended listening:

Orchestral

Symphony No. 4

Symphony No. 7

Symphony No. 6 (my personal favourite)

Choral

Te Deum

Mass No. 2 in E Minor

Christus Factus Est (WAB 11)

Os Justi (WAB 30)

Virga Jesse (WAB 52)

Locus Iste (WAB 23)

[i] Constantin Floros, Anton Bruckner: The Man and the Work, trans. Ernest Bernhardt-Kabisch (Frankfurt am Main: PL Academic Research, 2015), 48.

[ii] Constantin Floros, Anton Bruckner: The Man and the Work, trans. Ernest Bernhardt-Kabisch (Frankfurt am Main: PL Academic Research, 2015), 48.

[iii] Hans-Hubert Schönzeler, Bruckner (Wien: Musikwissenschaftl. Verl., 1970), 136.

[iv] Constantin Floros, Anton Bruckner: The Man and the Work, trans. Ernest Bernhardt-Kabisch (Frankfurt am Main: PL Academic Research, 2015), 49.

[v] “Putting Bruckner in Context,” The Irish Times, (October 04, 2002), accessed May 18, 2020.

[vi] Hans-Hubert Schönzeler, Bruckner (Wien: Musikwissenschaftl. Verl., 1970), 137.

[vii] “Requiem, Masses, Te Deum,” Musikwissenschaftlicher Verlag, accessed November 30, 2018.

[viii] R. J. Stove, “Anton Bruckner and God,” Catholic World Report, accessed November 29, 2018.

Bibliography

Floros, Constantin. Anton Bruckner: The Man and the Work. Translated by Ernest Bernhardt-Kabisch. Frankfurt am Main: PL Academic Research, 2015.

“Requiem, Masses, Te Deum.” Musikwissenschaftlicher Verlag. Accessed November 30, 2018. http://www.mwv.at/english/TextBruckner/Katalog/requiem.htm.

Stove, R. J. “Anton Bruckner and God.” Catholic World Report. Accessed November 29, 2018. https://www.catholicworldreport.com/2015/08/02/anton-bruckner-and-god/.

“Putting Bruckner in Context.” The Irish Times. October 04, 2002. Accessed May 18, 2020. https://www.irishtimes.com/culture/putting-bruckner-in-context-1.1097618