The celebration of the beheading of Saint John the Baptist – an expeditious entrance into heaven – is sort of a bookend to the summer; you may recall that June 24th, just after the end of spring, was the solemnity of his birth. Now, as summer draws to its close, we celebrate his death. A curious liturgical paradox, you might think, for why would not his death be a solemnity as well? Perhaps because it was his birth, not his martyrdom, that ushered in the dawn of the Christian era, for the Baptist stands as the bridge between the Old and the New Covenants. As Saint Augustine pointed out, his birth has traditionally been placed around the time of the summer solstice, when the Earth completes half her half-billion mile journey around the Sun, when the days begin to get shorter, as we move (yes, it’s that time already) towards Christmas, and the advent of the Messiah:

Christ must increase, and I must decrease.

Everything changed with the dawn of this New Covenant, and we as Catholics are called, even commanded, to approach temporal realities in a different way. As Saint Paul warns the Romans

Do not be conformed to this world, but be transformed by the renewal of your mind, that you may prove what is the will of God, what is good and acceptable and perfect (12:2)

What, really, does it mean to be ‘conformed’ to the world? What does the Baptist, who may well be called the patron saint of non-conformity, have to teach us?

Here is one thought: The ‘form’ (as in con-form) of the human person, as the Catechism teaches, is the soul, that immaterial and immortal principle which gives life and breath to the body. Although we are animals, and share with the animal kingdom a material, sensual body, we are not just animals, but infinitely transcend them by the presence of this soul, made in the very image of God, which the same God creates immediately ex nihilo. We do not always ‘feel’ that we have this mysterious thing called a ‘soul’, for the body, affected by sin, often weighs us down, and many days we feel just like tired old beasts of burden. But even in the doldrums of life, we must believe and hold that the immortal and immaterial soul exists, and gives life to those burdened bodies.

It follows from this that it is the soul which should therefore govern the body, not the other way around. John the Baptist was the paradigm of this order: For what the muddle of men find alluring, namely sensual delights, fame, fortune, ambition, reputation, he seemed to care nothing for, living on ‘locusts and wild honey’, alone in the desert, vested in camel hair (and try petting a camel sometime).

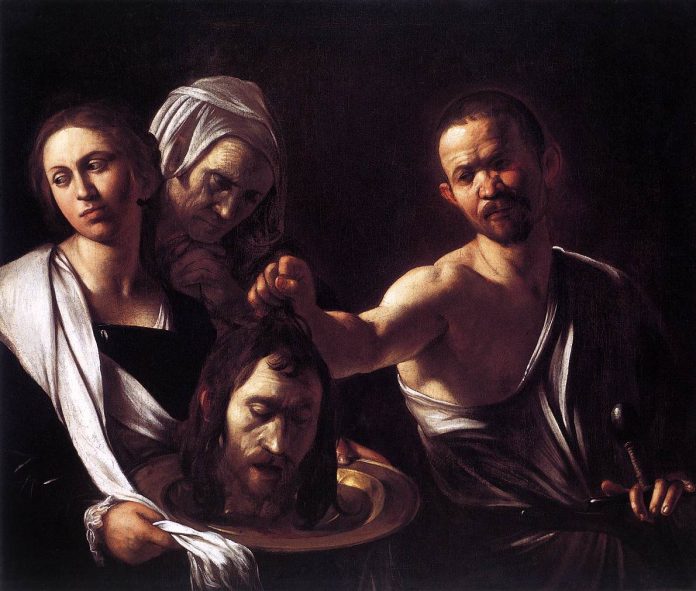

Herod, alas, poor Herod, reverted the order, and allowed his over-indulged sensual body to dominate his acratic soul. Smitten with the ‘dancing’ of his step-daughter (we may presume it was not a waltz, and not just for historical reasons) he made a rash, perhaps even drunken, promise. To maintain his honour and reputation amongst his (dis)reputable guests, he was willing, however reluctantly, to have an innocent man brutally murdered, a man whom he in some vague way respected and admired.

We see here the two ‘ways’ which Moses prophesied to the Israelites: The way of the commandments, which leads to life, and the way of sin, which leads to death.

We may look at this event more particularly from the vantage point of the two ‘rational’ powers in the soul, the intellect (or reason) and the will. The intellect ‘knows’, while the will ‘commands’ and ‘loves’. We may know the true and the good, but not will it, nor love it (as we see so often in our own lives). Conversely, we may will or love the true and the good, but not know it, or at least not know it fully. As the Imitation of Christ declares, it is better to feel contrition for our sins, than to be able to define it.

Of course, we must know some aspect of the true and the good to love it, for we cannot love what we do not know, but in the spiritual life, the will outstrips the intellect.

Here is the rub: As Saint Thomas teaches, when we know something in the world (whether real or imagined) with our minds, we bring that thing up to our level: In knowing a tree, we universalize the tree, in a sense knowing all trees.

Yet when we love something in the world, like triple-chocolate cheesecake, our wills go ‘out’ to the object, and we conform ourselves to it. When we add our unruly passions to this mix, things can get very severely disordered and evil. Look around at the effects of pornography, drugs, alcoholism, avarice, gambling, and vice of all sorts. We become what we love, more than what we know.

That is why Saint Thomas states that it is better to love God than to know Him, for we can only know Him according to our own capacity (rather limited, from God’s infinite perspective), but we can love Him as He is in Himself (of which there is no limit). In the end, we will be judged on our love of God, not our knowledge.

Hence, we are admonished not to love the things that are of this world, at least insofar as these things are contrary to the love of God, for in doing so, we conform ourselves to them, with all of their emptiness and transitoriness, the form of which is already passing away. This is a subtle phenomenon, not happening all at once, but gradually, over time, as the ‘world’ inexorably entangles our souls its in sticky web with every compromise and capitulation to its way of thinking. Get behind me Satan, Our Lord rebuked Saint Peter for you are not on the side of God but of men.

So many of us think in the world’s terms, and what the world deems ‘success’. Rather, we must, with each moral decision, from the least to the greatest, continually conform ourselves to God and His way of ‘seeing things’, and so be transformed into His likeness.

I wonder about that moment of choice in the soul of Herod, as he hung in the balance before the daughter of Herodias, his unlawful wife. At least in that instant (we know not his eternal destiny), he conformed himself to the ‘world’, loving what he should not love, while rejecting what he did know, even inchoately.

Contrast the sad and tragic figure of Herod to the strength and vigour of John the Baptist, who conformed himself to what he, and we, should truly love, and that all of our ‘loves’ this side of the grave must be subordinate to this pure and undistilled love of God. If any of the passing things of this life lead us astray, out they must go, and uprooted they must be, even if it means the loss of our heads, to say nothing of our reputation.

Saint John the Baptist, ora pro nobis! +