I heard recently a homily from a traditional priest, the theme of which was how often we should receive Holy Communion, which topic, funnily enough, also came up in a conversation I had with a friend just before that. The argument seems to be as follows: The purpose – the fruit – of Communion is to produce holiness in our souls. Less devotion means less holiness, and more devotion, more holiness. And one way to increase devotion, it is posited, is to receive less often, so that we ‘work up’ devotion, much as, I suppose, eating steak everyday would decrease our appreciation for steak. Only when we are properly and sufficiently devout, should we receive.

I can see the point, for it can all seem so prosaically ho-hum, hum-drum too much of the time. Confessions in many parishes have been reduced to the vanishing point, while the lines for Communion are full (for those still attending Mass, for they’re not as full as they used to be). James Joyce’s quip about the Catholic Church, ‘here comes everybody!’ should not apply to reception of the Holy Eucharist for those persisting in ‘manifest, grave sin’, or those still outside the Church (the two are not necessarily the same thing, if such needs pointing out). Bishops might start by enforcing canon 915, which is in grave danger of being perverted by the German synodal way.

But is reducing reception for those striving to live a full Catholic life the solution to their own (apparent) insufficient growth in holiness, and the sacrament bearing its proper fruit in our souls?

Here are my own two cents on the matter, which I do not in any way claim as the last word, and rebuttals are welcome; only to offer some principles and distinctions that I hope may help the reader:

- None of us is worthy to receive the Body and Blood of Christ, which is why we pronounce the ‘Domine, non sum dignus…’ before reception. We are all sinners, and none of us produces the full fruit of Communion. As the Curé d’Ars once quipped, one Host should make us a saint, if we received with full devotion.

- The sacraments work primarily ex opere operato, which literally means ‘from the work being worked’, but which implies that they are primarily God’s work, not ours. Their purpose is for Him to infuse grace into our souls in a sensible manner.

- In order for God to so work in our souls, some devotion is requisite, but the Church has taught that this is minimal. Yes, more devotion means more fruit, but a little bit is all God requires. The Jansenist heresy – the complexity of which goes beyond these few words – obfuscated this, teaching that great devotion, even freedom from all deliberate sin, was required to receive, making Communion more a reward for the virtuous, than a medicine and food for the sinful pilgrim.

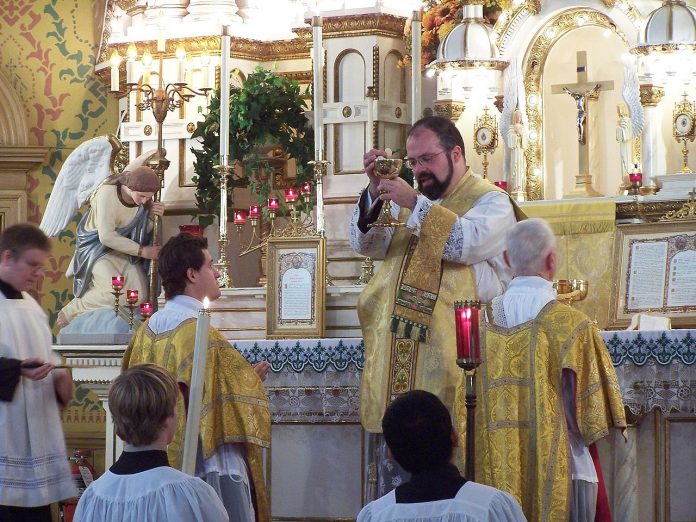

- Of course, there are limits, which were clarified by Pope Saint Pius X in his 1905 Apostolic Letter Sacra Tridentina, which all readers should one day peruse. Therein, he responds explicitly to the Jansenist heresy, and states that the requirements to receive Communion are three: First, freedom from mortal sin. Second, that we keep the required fast. Third, that we receive recta piaque mente, with a ‘right and pious mind’. He clarifies this last point, most pertinent to our discussion, that it does not mean we need approach with great and fervent devotion, but with some: A right intention consists in this: that he who approaches the Holy Table should do so, not out of routine, or vainglory or human respect, but that he wish to please God, to be more closely united with Him by charity, and to have recourse to this divine remedy for his weakness and defects.

- That said, Holy Father does admit that more devotion is better: In his own words: Since, however, the Sacraments of the New Law, though they produce their effect ex opere operato, nevertheless, produce a great effect in proportion as the dispositions of the recipient are better, therefore, one should take care that Holy Communion be preceded by careful preparation, and followed by an appropriate thanksgiving, according to each one’s strength, circumstances and duties.

- In a sermon that prompted these thoughts, the good priest mentions a list of things that may prevent our reception, such as not preparing properly before Mass; watching YouTube on the way to Mass; not making a proper thanksgiving after Mass; cutting the time of the fast down to the wire, and so on. With such requirements, harried parents with a platoon of rambunctious children could almost never go. These may all be less-than-optimal, but should they preclude reception, if one is still approaching with what is at least required?

- It is a perilous thing to judge our own state of devotion or holiness, and too much of this seems to depend on our own will and discernment. We would tend either to presumption: Now, I’m ready, and God will do great things in me! based on some feeling or awareness of devotion. Or, perhaps more often, to scrupulosity, that our devotion is rarely ever requisite, and so slip imperceptibly back into a quasi-Jansenism. How devout is devout enough? And how often is often enough, or too often? How would we avoid divisions amongst parishioners, even within families, wives going to receive, and husbands not? Who’s to say who has more devotion? I’m reading the life of Saint Anna-Maria Taigi, wife, mother and mystic, who lived a life of near-unparalleled sanctity. Yet she considered herself a great sinner, and asked her confessor if she could go to confession everyday, and Communion once a week. He said – and this was in the early 1800’s with the effects of Jansenism very much lingering – no, the other way around: Daily Communion, and weekly Confession. Not bad advice, that.

- Holiness is, for most of us, a gradual, laborious process, lifelong, and nearly imperceptible, sort of like growing old. You don’t think you’re there, ’till you’re there. We may not see the full fruits of Communion, or even Confession, for weeks, months, years. But God is working – ex opere operato! – through the ordinary ‘humdrum’ events of daily life, like water carving a beautiful shape in rock. At times He may use a hammer and chisel, but often the divine physician prefers to operate on us suaviter et fortiter, sweetly, but strongly nonetheless.

- Holy Mass and Communion are not like other religious practices, which we may pick and choose, take or leave, according to our proclivities. The Eucharist is the sacrament of sacraments, to which all the rest, and our entire lives, are ordered. Our Lord taught us to pray for our ‘daily bread’, which, as the Church has clarified, refers directly to the Bread of Life, the Body of Christ (CCC, 2837). If He desires to come into our souls daily, though we be distracted and undevout sinners, why would we refuse Him?

Of course, not all of us can make it to daily Mass, for various reasons, not least that it is getting harder to find, and they’re often at awkward times best suited to retirees and people on holiday. God can, in His munificence and mercy, supply the effects of the sacraments without the sacraments, so we make do with what we can do.

But if we can get to Mass, and have the minimal requirements as outlined by Pope Pius – free from mortal sin, and not going purely out of habit or vainglory (which themselves are spiritually problematic) and having kept the fast, now rather minimal and symbolic – we should not hesitate. The solution to our lack of fervour seems to me not to reduce reception, but to remove the obstacles to our devotion: The daily faults and failings which we do not fight hard enough; acedia caused by over-attachment to, and over-indulgence in, sensual pleasures; the whole ‘lust of the eyes, lust of the flesh and the pride of life’ against which Saint John warns.

Daily Mass and Communion are not obligatory, but they are a beautiful treasure and remedy from God for our faults and failings, not a reward for having already overcome them. The institution of today’s feast of the Sacred Heart in the 17th century corroborated a greater appreciation of the benefits of frequent, even daily, Communion: God bestowing on us His mercy – and His very Body and Blood – through His humanity in Christ.

So prepare and pray as you are able, and let Him do the rest. If we but persevere, day by day, little by little He will make saints of us yet.