Nothing really changes much anymore. In contrast to popular assumptions, the pace of actual cultural innovation and renewal, even with regard to what undeservedly passed as such during the late 20th century, seems to have stalled, the flow having receded to a drip. And whatever actually emerges in the cultural sphere today is increasingly vapid and lacking in originality, utility and robust meaning. The only exceptions appear to be such artefacts which relate to our nostalgia for bygone days and our preoccupation with the apocalypse.

Obviously, change in the most literal sense of the word is as rampant as ever within the confines of Western industrial society and its borderlands. The political and economic landscape has arguably undergone more radical transformations during the last fifteen years, than in the entire preceding period since the end of the Second World War. The socio-cultural upheavals of the displacement of vast numbers of people in the wake of the conflicts related to the War on Terror, and the global economic deterioration of the last decades, not to speak of environmental degradation, must obviously be regarded as instances of brute change as such.

Yet these phenomena are more akin to distortions than anything else. They are for the very most part examples of an unravelling, instead of constructive, creative or useful developments. They exemplify the erosion of industrial civilization’s institutions and societal infrastructure, rather than the emergence of potentially fruitful, or even novel, cultural adaptations. The latter have indeed become much more rare than ever before, which becomes obvious if one studies the picture closely. It can be seen across all areas of contemporary Western culture, in everything from the declining rate of actual ground-breaking developments in science and technology and the stagnation and sterility of academia in general, to the equally barren tendency towards conceptual recycling in the arts, in film and literature. Nowadays, we seem to merely subsist on what was provided to us by generations past, contributing almost nothing novel ourselves.

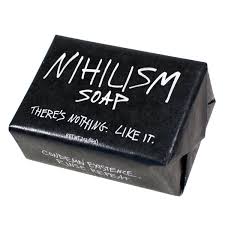

For instance, remakes of popular movies from earlier decades, or rehashes upon rehashes of time-tried concepts, now euphemistically advertised as “franchise reboots”, are within the film industry almost exclusively favoured over anything approximating innovative or experimental productions. Literature is basically dead, with a drastically declined percentage of leisure readers, even with regard to such ostensible pablum as comics and magazines, and no great novels, accurately and in detail portraying the active spirit of our age, resonating with a wide and heterogeneous audience, have been written since at least the mid-90s. Fight Club was with its many flaws in all likelihood the last great American novel, the widely resonating lament of the “middle children of history”, suffocating in the secular emptiness of Fukuyama’s triumphant capitalism, desperately searching for a meaning that had been denied them, searching for a way to smash this strange madness of our post-modern consumerist utopia and reconnect with something authentic. Now, even this spirit of possibly fruitful rebellion seems to have been snuffed out by a superficial complacency, despair and nihilism.

Cultural theorist Mark Fisher described the late-modern zeitgeist as essentially hauntology. The preoccupation with past hopes for a lost future.[1] His analysis as applied to our contemporary situation appears all too plausible today. It does indeed seem like all that is really innovative, all popular culture that is the least bit vibrant and vital in this age, is depicting our being haunted by the loss of possible futures that will never come to pass – haunted by the very loss of the hope of a better tomorrow. A good example that epitomizes the situation is the acclaimed television drama Rectify. This show tells the story of a wrongfully convicted man, who after two decades of incarceration on death row is being released into a bleak and confusing reality, initially with nothing to call his own but the perversely undead hope of reclaiming his possible past.

Another telling phenomenon of this our contemporary hauntology is the strongly resurgent pop-cultural nostalgia, especially with regard to the 80s. This nostalgia is widespread, but particularly evident in the newly emerged, rather vital musical genre (one of the very few around) generally known as “Retrowave”, which unabashedly recycles aesthetics, themes and soundscapes of 80s electronic, film and video game music. Retrowave and associated sub-genres can in turn be positioned as a more unapologetic offspring of Vaporwave, a musically anchored, web-based art movement which began in the early 2010s as an openly cynical and strongly critical, yet fundamentally nostalgic rehashing of the spiritually deadening 80s and early 90s consumerist aesthetics and popular culture.

The 80s and early 90s, in a certain sense symbolizing the comparatively innocent childhood of us ascendant millennials, also, in retrospect, represents the last vestiges of the Western hopes and dreams of triumphant progress. The capitalist economy was close past its zenith, and we still had great faith in the utopias and mesmerizing future vistas promised by science and technology. We believed ourselves to have very nearly, but not quite, vanquished the great evil of totalitarianism, so the ongoing battle provided us with a common sense of purpose, all the while triumph seemed clearly within reach.

And then came upon us the bleak end of history, with its profoundly unfulfilling paradise of consumer choice demanding neither struggle nor virtue. The stagnated, utopian promises of technology finally reduced to escapist online gaming and internet pornography, and the empty, unchaste self-gratification of a hedonistic society with neither purpose nor goals. Even this scientistic era’s hope for pseudo-transcendence was erased in the demise of the Age of Space, as the realization crept upon us that we’d lay waste to the earth itself long before humanity’s seed would spread far and wide among the stars.

Indeed, a prerequisite for any such deep fixation upon nostalgia and lost opportunities as characterizes contemporary culture, is of course the looming threat of an apocalypse in some form or other. Accordingly, abundant and vivid fantasies of the end-times are infiltrating popular culture from many directions, not least as featuring in several prominent television series aside from the one just mentioned. Such fantasies are seemingly, together with the nostalgic partaking in the haunting memories of yesterday’s hopes, one of exceedingly few truly living cultural forms in today’s mainstream. Global modernity seems to be actively coping with death in various forms, its denizens coping with the proceeding demise of our culture, and the loss of civilization as such, which we intuitively sense lies close ahead.

This basic sentiment completely saturates the heart of today’s political and ideological vanguard in the broadest sense. Movements all across the spectrum, from the ascendant Alt-right in the US and the populist and neo-fascist reaction in Europe, to the radical left revival and its green anarchist leanings, are fuelled by this fundamental sense of loss and impending catastrophe, interpreted in various ways. The political culture of our era seems to have an apocalyptic subconscious of a most definite kind, characterized by a hopelessness that wasn’t even at hand during the worst crises of the Cold War, because then one could still plausibly expect that the modern world faced a bright future.

However, from the Christian perspective, as well as of most other religious traditions, the utopian promises of modernity were always hollow, even outright ghastly; the notion of an imminent salvation by mankind’s own hand to be written off at the outset. Our tradition fixed our hopes firmly with God, even as the fields lay white with harvest, artificially fertilized and worked by draining the black blood of the earth. While mankind deluded itself to be the master of its own destiny, destroying untold millions of lives and laying waste to our inherited home in the process, we would recall the perennial truths of her tradition, admonishing us not to fall in with such vain delusions. Again and again, we are reminded that all our toils are in themselves empty and meaningless, that only God can bring forth fruit out of this barren wasteland, and finally, that our hopes must not be for this world, for we are called beyond it.

As we approach the end of modernity and the limits of the secular era of growth-based material progress, it does not befit the Christian to despair. Not only has the Church weathered such storms before, but the very goals of this civilization, the inherent télae of modernity, are themselves fundamentally inimical to her. The City of Man may crumble in the tumultuous era ahead, but what little virtue it still retained will surely be preserved in the communities of faithful, the latter laying new roots as the cracks in the ageing asphalt widens, while the tide will flush much debris out to sea.

This debris, the culture of late-modern industrial society – as has been realized at both ends of the political spectrum – is really little more than a spectacle designed to reproduce and inculcate a secular, consumerist ethos and order of production, which itself is essentially a theatre. This partly lies in the fact that the gratuitous consumption fundamental to our society is driven not by need, but by wants related to the construction and maintenance of “identities” and “lifestyles” paraded about in a collective charade with little connection to authentic human realities. Thus, to paraphrase Guy Debord, cultural Marxist par excellence, spiritually lifeless mass culture in late-modern capitalism is just a spectacle for the sake of maintaining a spectacle.[2] Lacking a transcendent focal point, it becomes merely a reproduction of itself, which is why the very best that contemporary nostalgic culture is really capable of aiming for, having lost faith in the eschatological narratives of industrial society and having no dreams left of its own, is to reproduce the spectacles of yesteryear wherein such a narrative was still retained, in a kind of requiem for lost hope.

Such a culture is clearly dead. But a certain number of seedlings and fragments defiantly holding out in proximity to the oases of truth dotting the landscape are most assuredly not, however flawed.

We, as Christians, have a clear obligation to provide nourishment and guidance for such embryonic ways of life of future society. We have a duty to dissociate from the sterile spectacle and instead more fully partake in and revitalize our tradition, firmly anchored in virtue and truth. In no other way can we facilitate the transition beyond the contemporary and approaching crises into a resilient, morally sound and sustainable future society, whatever shape it may take.

There is no reforming of secular modernity. The first element in Vaporwave, derived from “vaporware”, commercial software which was announced and promoted but failed to materialize, serves to emphasize the broken promises of end-stage capitalism. Having thus lost every semblance of a plausible narrative of salvation, secular modernity has no life, and can bear no more fruit. While it might not be entirely appropriate to mourn its demise, we would nonetheless do well to honour the countless lives spent under its rule, and whatever good there was in the broken, albeit misdirected dreams upon which it was built. Truly, as Alphaville contended in 1984, there are so many songs we forgot to play.

But the future is yet uncertain. To what extent will we as a society, seated amidst all our broken, impotent idols, finally turn back to the Lord and bear the disgrace of our youth? Will we not rather attempt to fashion them anew, using the now viciously jagged bits and pieces strewn about?

What we can be sure of, however, is that lacking a steadfast witness to the perennial truths far beyond all the simulacra that spectacular, secular ideology can provide, we will all too easily be enthralled by the old, familiar lies once more – and in their undead form, bitterly promising the return of a lost, earthly paradise taken from us when it was just within view, they may well prove quite lethal. The effort to recover what is believed to have been lost is not rarely more uncompromising than mere preservation. Thus, what now manifests as mere nostalgia risks mutating into a desperate search for lost time, where the passionate sentimentality and apocalyptic fantasies of our day combine in a struggle to recover the forgotten path towards a secular greatness that we never really achieved, and never could.

For this reason, the living authenticity of Christian orthodoxy and communal unity is particularly critical in this period. Contrary to the trends towards greater integration and compromise with the ethos of secular modernity, we should really not yield an inch. Because if Christians cannot provide a clear and coherent worldview grounded in the truths preserved by the Catholic tradition, serving to guide society in accordance with the Gospel in the midst of cultural decline, there really is nobody else that will.

[1] Mark Fisher, “What is Hauntology?”, Film Quarterly, vol. 66, no. 1 2012

[2] Guy Debord, Society of the Spectacle, London: Rebel Press 2005