“ontology” defined ~ the science of being

Some students are fortunate enough to have had a teacher who made all the difference in life. I am such a person. During my junior year of high school in Carlsbad, New Mexico, John Hadsell was my English teacher. One day, apparently bored with the insipid materials in our English textbook, he took it upon himself to conduct an experiment that might have gotten him fired if he tried it in a public school today. He read aloud a paragraph from St. Anselm’s Proslogion, the so-called “ontological” proof for the existence of God. I sat still and eager for what was sure to be a fascinating revelation. When the proof was read to us, there was a general silence, everybody including myself quite perplexed at what we had just heard. I did not understand the proof, but I had just an inkling of what Anselm was trying to convey. I asked Mr. Hadsell if he would mind reading it again, which he did. Again, the classroom silence was deafening. This so-called “proof” started me on a lifelong search for the philosopher’s stone, the thing called Reason, which transforms foolishness into wisdom, without which we are lost in those regular fogs of mostly blissful ignorance all life long.

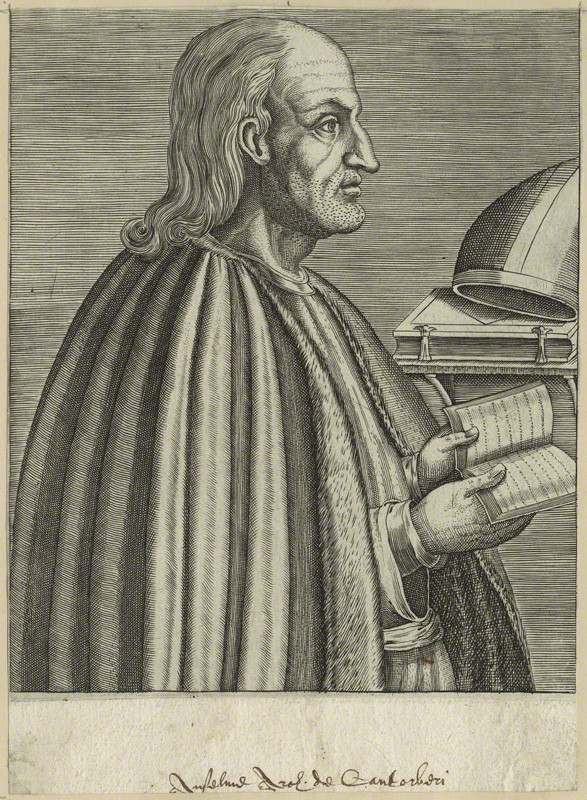

Saint Anselm (1033-1109) was an Italian by birth, an Englishman by adoption, and a defender of the rights of the Catholic Church against the opposition of the English Crown. He was the scourge of two kings, yet rose to become Archbishop of Canterbury and was, by some accounts, the fountainhead of medieval philosophy and theology. Like Augustine before him, amid all the whirlwind of politics and persecution he found time to write several brilliant theological treatises that should be required reading today for students of Catholic theology. His Proslogion (Discourse) is perhaps the most famous of them.

Faith and Reason

In a chapter titled “Arousal of the mind for contemplating God” Anselm complains desperately of his inability to know God up close and personal. How is it, he asks, that we were made to seek God, but do not see the light that shines our way toward him? Why does the chamber door into his presence seem closed rather than open? And now Anselm waxes sublime, as did Augustine before him and Pascal after him:

Teach me to seek You, and reveal Yourself to me as I seek; for unless You teach me I cannot seek You, and unless You reveal Yourself I cannot find You. Let me seek You in desiring You; let me desire You in seeking You. Let me find You in loving You; let me love You in finding You. 0 Lord, I acknowledge and give thanks that You created in me Your image so that I may remember, contemplate, and love You. But this image has been so effaced by the abrasion of transgressions, so hidden from sight by the dark billows of sins, that unless You renew and refashion it, it cannot do what it was created to do. 0 Lord, I do not attempt to gain access to Your loftiness, because I do not at all consider my intellect to be equal to this task. But I yearn to understand some measure of Your truth, which my heart believes and loves. For I do not seek to understand in order to believe, but I believe in order to understand. For I believe even this: that unless I believe, I shall not understand.

The Proof

Clearly, Anselm is talking about believing in the possibility of a God who has created us in his image for an intimate and loving relationship with Him. If God is impossible to believe in, in the same way that a round square is impossible to believe in, we could not believe in God at all. Once we grant belief in this possibility of God, we may go on to examine whether reason supports such a belief. Anselm then suggests that if there is a single definition of what God is, it is that God is a Being of which no greater being can be thought. Once we have that definition in our understanding, we have to make a logical leap. We have to concede that such a Being that exists in our understanding must exist in reality as well, which is greater than existing in the understanding alone.

And so, Anselm concludes,

Therefore, if that than which a greater cannot be thought were only in the understanding, then that than which a greater cannot be thought would be that than which a greater can be thought!” Clearly, something than which a greater cannot be thought must exist both in understanding and reality, or it would be less than those things which exist both in the understanding and in reality. Moreover, God cannot be thought not to exist. Why? Because if that were to happen, if a mind could think of something better than God (making it therefore certain that God does not exist as the Being of which no Being greater can be conceived) then the creature would sit in judgment of the Creator, and therefore that creature would be, as Scripture says (Psalm 14:1), the fool who in his heart says there is no God; but he only says this because he has fooled himself.

God’s Nature

God knows without the senses, the method by which humans know. The human senses are limited by their natural powers, and humans cannot know everything; God, on the contrary, does not possess senses, and therefore, being that Being of which no being greater can be conceived, God knows everything (is Omniscient). By the same token, while human power is limited, God is omnipotent, there being nothing in existence to restrict His power because everything else that exists is only possible through His power. God’s power is limited only by His own will; He cannot, for example, think or do evil because evil is by its essence only found in beings who will let evil prevail over them, and God by definition cannot be subject to any created power.

God is Merciful and Just

Also, God is merciful without being compassionate. God sees our suffering and assuages it as He will, but does not feel the emotion humans feel when they experience pity. This is because God knows our needs, and answers to our needs when justice is served by His answering. Addressing God, he says:

You reward with good things those who are good and with evil things those who are evil, the principle of justice seems to require this. But when You give good things to those who are evil, we know that He who is supremely good willed to do this, but we wonder why He who is supremely just was able to will this.” And the answer is that God’s justice is toward all. Those who do evil do so because they are weak, and God’s justice flows from him in the form of mercy, lifting those who are evil into a realm by which they can become good. Thus it is that Adam and Eve did evil, but God’s justice lifted them and all their progeny out of their banishment through the merciful person of Jesus Christ.

Addressing God again, Anselm ends by uttering a paradox:

For only what You will is just, and only what You do not will is not just. So, then, Your mercy is begotten from Your justice, because it is just for You to be good to such an extent that You are good even in sparing. And perhaps this is why He who is supremely just can will good things for those who are evil. But if we can somehow grasp why You can will to save those who are evil, surely we cannot at all comprehend why from among those who are similarly evil You save some and not others because of Your supreme goodness, and condemn some and not others because of Your supreme justice.

Why we cannot see God as He is.

Then Anselm complains to God of the need to seek Him, but seek Him only in darkness. And why is darkness all around his soul? Is it because the soul is so far removed from the light, or because the immensity of God overshadows the soul’s clarity of vision? Yes, the soul can get a glimpse of God by the fact that it sees reflection of God in whatever light and truth it does grasp in the world. So now Anselm tries to grasp the source cause of atheism.

Therefore, if [my soul] saw light and truth, it saw You. If it did not see You, it did not see light and truth…. My soul strains to see more; but beyond what it has already seen it sees only darkness. Or better, it does not see darkness, which is not present in You; rather, it sees that it can see no farther because of its own darkness. Why is this, 0 Lord? Why is this? Is the eye of the soul darkened as a result of its own weakness, or is it dazzled by Your brilliance? Surely, the soul’s eye is both darkened within itself and dazzled by You. Surely, it is darkened because of its own shortness of vision and is overwhelmed by Your immensity; truly, it is restricted because of its own narrowness and is overcome by Your vastness….

Anselm concludes that this dim vision of God, this darkened soul, is only so because the soul is “impaired by the old-time infirmity of sin” inherited from Adam. Had Adam not sinned, had he not been banished from the vision of God in Eden, we would see God as Adam had first seen him. And what would we have seen? He would not have seen a God composed of part or existing in time. No, because God is a oneness that contains many things – life, wisdom, blessedness, etc. – not as parts but as an eternal whole. Again, that is a reason we cannot see the Wholeness that is God because we are made only to see parts that make up that Wholeness. We exist in parts, and the parts cannot grasp the Whole as Whole, though we can have a glimmer of the Whole by virtue of the fact that even though we exist as parts, the only reason we exist at all is that we exist in Him, and therefore we naturally (and supernaturally) reach beyond ourselves to be made whole in Him, as he designed us to be. “For You are not contained by anything, but, rather, You contain all [other] things.” The creature reaches out to the Creator, as a child naturally reaches out to its parents even when it only dimly perceives them to be the origin of its being.

God is eternal.

God is eternal, not as an endless series of eons, but as a self-subsisting Whole that is without parts. There is no past, present, or future in God, for God does not exist in time, but in Himself, Who is the Creator of time. The same is true of God’s infinite immensity, which we would measure as vast beyond measure, and therefore beyond understanding. So, Anselm concludes: “And You are life and light and wisdom and blessedness and eternity and many such good things. Nevertheless, You are only one supreme good, altogether sufficient unto Yourself, needing no one else but needed by all other things in order to exist and to fare well.”

God is love.

Moreover, God is One, God is wholly One, and the Father Loves the Word, the Word loves the Father, and they conjoin their love in the Holy Spirit as One. It is by the Word (Jesus) that we begin to approach God more nearly, for Jesus is both God and Man. The Word came in the fullness of time, loved, preached, sacrificed himself out of love for his creation; so man is now able to grasp in his parts the life of Jesus, through his coming to us and rescuing us from darkness, a closer glimpse of the Whole and One God. Through the Word Incarnate we are able to see more clearly that God is the “one good, complete good, and the only good.” And so when we become one with God in heaven, we leave behind our incomplete and imperfect good to enter in the one complete and only good. This will be the resting point that all life is directed to, the peace of soul that every heart desires. Anselm concludes:

Now, surely, no eye has seen, no ear has heard—nor has there entered into the heart of man—that joy with which Your elect ones will rejoice. Therefore, I have not yet said or thought, 0 Lord, how much Your blessed ones will rejoice. Surely, they will rejoice in the degree that they will love. And they will love in the degree that they will know. How much will they know You in that day, 0 Lord? How much will they love You? Surely, in this life no eye has seen, no ear has heard, nor has there entered into the heart of man how much they will know and love You in the next life.

Thus has Anselm explained God as an Immensity beyond understanding, the Being beyond which no greater being can be conceived, and the reason why so many throw up their hands in disbelief and resign themselves to never truly seeking or finding the love and the joy beyond all understanding, that same love and joy we only get a fleeting glimpse of in our home away from Home.

Post Script

The monk and philosopher Gaunilon, one of Anselm’s contemporaries, rejected the ontological proof as specious reasoning. It could apply to anything one wanted to claim as perfect; for example, a perfect island would have to exist in reality as well as in the understanding. Thomas Aquinas also rejected the proof as circular reasoning, since it presumes to know an aspect of God (a Being of whom no being greater can be conceived) before proving that God exists. According to Aquinas we must by other means prove that God exists and only afterward move to the description of God’s main attribute, a Being of which no greater being can be conceived. Yet among Aquinas’s five proofs for God, the fourth proof, after careful consideration, seem rather close to being an alternate version of Anselm’s proof.

Likewise, Immanuel Kant repudiated “existence” as in any way a property of anything. Rather, existence contains properties, or accidents, or essences that are variable from one existing thing to another. For Kant, Anselm had failed to provide a bridge from the essence of God to the existence of God. Moreover, since the truth of God’s existence is not subject to verification, as other truths are, God is not provable to exist simply by thinking about Him. Kant’s refutation is reminiscent of the arguments of Gaunilon and Aquinas.

On the other hand, Descartes, Leibniz and Hegel found Anselm’s argument appealing in one way or another. Bertrand Russell was impressed by the argument, but later in his History of Western Philosophy repudiated it, saying “… it is easier to feel convinced that it must be fallacious than it is to find out precisely where the fallacy lies.” Even so, the “proof” continues to exert its appeal for many who seek to believe in order to understand. The current most notable defender of the ontological argument, somewhat modified, is the eminent Protestant philosopher Alvin Plantinga. Following Augustine and Anselm, Plantinga has said, “Faith is the belief in the great things of the gospel that results from the internal instigation of the Holy Spirit.” In other words, God leads us to believe in order to understand.

Volunt credunt, ut intelligant.

St. Anselm’s feast day, April 21