(We are soon approaching the feast of Saint Albert the Great, Dominican, teacher of Saint Thomas, and patron saint of scientists on the 15th of this month. As a prelude, here is a reflection from contributor Carl Sundell on Albert’s Franciscan predecessor, Roger Bacon) Ed.

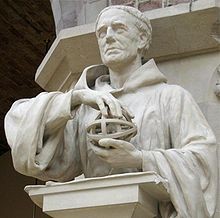

Roger Bacon was a contemporary of the great theologian Thomas Aquinas (both of them taught at the University of Paris within a few years of each other, but there is no evidence that they knew of each other’s works). He was educated at Oxford and Paris, later became a professor at Oxford, and was ordained a Franciscan priest about 1240. In the course of his studies he proved to be a prophet of inventions so impressive that Pope Clement IV urged him to secretly send manuscripts to him for examination. Some of these same ideas had caused Bacon’s Franciscan superiors to doubt his orthodoxy in religious matters, but the Pope gave Bacon as much leeway as possible to continue his work. Then Clement IV died prematurely, at least with respect to advancing the interests of Bacon, whose standing continued to fall as his superiors grew increasingly suspicious of him.

The most important works by Bacon include the Opus Majus, the Opus Minus, and the Tertium. In these works Bacon brings major charges against the “sinful” scholarship of his times, far too weighed down by metaphysical speculations and a nearly complete disregard for the great importance of mathematics and the experimental sciences. As he said, “All science requires mathematics. The knowledge of mathematical things is almost innate in us. This is the easiest of sciences, a fact which is obvious in that no one’s brain rejects it; for laymen and people who are utterly illiterate know how to count and reckon.”

Bacon indicted the theologians of his day not only for widespread ignorance, but also for willful distortion and corruption of the sacred truths of the faith. This at least partly, along with his perhaps excessive zeal in protesting, placed him in a difficult position to advance his own ideas, so that they remained buried for centuries before they could be resurrected by later scholars following Gutenberg’s invention of the printing press.

We examine now some of the things that mattered most to Bacon. Perhaps first we should acknowledge the style of the man. He was not simply the intellectual, but also the aesthete. For him science had to be both true and eloquent. “Science without eloquence is like a sharp sword in the hands of a paralytic, whilst eloquence without science is a sharp sword in the hands of a furious man.” Moreover, the eloquence of scriptures cannot be obscured or contradicted by the eloquence of science. But eloquence is not merely literary. Eloquence is also the description of things as they really are. “The strongest arguments prove nothing so long as the conclusions are not verified by experience. Experimental science is the queen of sciences and the goal of all speculation.” This viewpoint, so unusual in its day, may well have spurred that later seer of science, Francis Bacon, as he helped pave the way in his Novum Organum for the rise of modern science.

Bacon also presented as an ideal what we today call the Renaissance Man, the well-rounded scholar who knows not only foreign languages, scriptures, and moral philosophy, but who also has a practical knowledge of how to test and prove a scientific hypothesis. That moral philosophy was a requirement along with other scientific disciplines shows how much Bacon was not only far in advance of his own time, but also of the modern era in which the scientific community has been largely dominated by atheism and antagonism toward religion and traditional morality.

In many other ways Bacon was, like Leonardo da Vinci, a man born centuries ahead of the day, when his talents might have greatly flourished and borne fruit. For examples, he imagined a great ship being operated by one man without the need of oarsmen (steamships), a machine that would make possible the walking of men along the ocean floor (the diving bell), and a vehicle that could be propelled below water (the submarine). He also imagined a vehicle operating at high speeds without the need of any horsepower (the automobile), and a machine with a mechanical device in it that would make it fly above the earth.

Like the future Isaac Newton, Bacon became absorbed in the science of optics. He theorized that “Someday we may read the smallest letters at an incredible distance (binoculars) we may see objects however small they may be (microscopes) and we may cause the stars to appear wherever we wish” (telescopes). As for a new technology of light, there may sometime in the future appear “that device by which rays of light are led into any place that we wish and are brought together by refractions in such fashion that anything is burned which is placed there” (laser technology). These inventions would all take six to seven more centuries to materialize.

Bacon also pointed out the deficiencies of the Julian calendar which would lead three centuries later to the more accurate Gregorian calendar. It is true that the tardiness of the reception of his ideas about the calendar may have been related to the general neglect and suppression of Bacon’s entire work by his superiors. That Bacon was not able to be a scientist of the sort that he most admired was not his fault, nor the fault of the Church. Scientific “laboratories” of the type he envisioned were not yet known to be possible. Very likely his speculations, especially in the dangerous areas of astrology and alchemy condemned by the Church, led his superiors to think of him as an idle eccentric who needed to be placed under arrest for his own good and the good of the community. But his ideas, though undeveloped for centuries, were never entirely extinguished. His writings exist to prove that he was at least the prophet par excellence of a scientific priesthood that sorely needs today, as never before, to be devoted to the True, the Beautiful, and the Good.