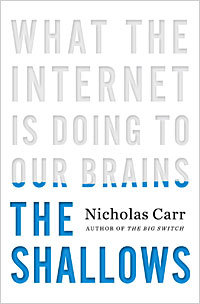

If you are an average web-surfer, chances are you will spend about 10 seconds looking at this article. Those of you who stick around for a little longer will probably read 18% or less of the content on this page. That, at least, was the finding of a study conducted by Jokob Nielsen, a web-page design consultant, and presented in Nicholas Carr’s book, “The Shallows: What the Internet is doing to our Brains”. In the book, Carr sets out to answer the question of how the Internet changes the way we think and the chemistry of our brains.

After prolonged exposure to the Internet, Carr began to notice changes in his intellectual habits. He says:

Over the last few years, I’ve had an uncomfortable sense that someone, or something, has been tinkering with my brain, remapping the neural circuitry, reprogramming the memory… I used to find it easy to immerse myself in a book or a lengthy article… I once was a scuba diver in the sea of words. Now I zip along the surface like a guy on a Jet Ski.

Carr distinguishes between four types of tools. (1) Those that increase our physical strength (the plow, the hammer). (2) Those that increase our sense of perception (the telescope, the stethoscope). (3) Those that interact with the environment (windmills, solar panels), and finally (4) intellectual tools (the map, the clock, and of course, the Internet).

Intellectual tools are unique, because they actually change the brain function of the people who use them. The clock, for example, “helped create the belief in an independent world of mathematically measurable sequences”.[i] The idea that tools change us is nothing new. Socrates was initially critical of writing; he believed that recording thoughts and information would make people lazy and decrease the faculties required for reflection and memory. Nietzsche observed that the use of a typewriter changed the contents of his writing. In a letter to his friend and composer Wagner, he noted, “Our writing equipment takes part in the forming of our thoughts.”

Remember to remember

One danger posed by the Internet is the loss of control of our attention. Not having the ability to focus on what we want to focus on may seem innocent enough. However, Carr warns us that the loss of this faculty can have dire consequences. The author David Foster Wallace at a commencement speech for Kenyon College said:

‘Learning how to think’ really means learning how to exercise some control over how and what you think… It means being conscious and aware enough to choose what you pay attention to and to choose how you construct meaning from experience. [to give up control is to be left with*] the constant gnawing sense of having had and lost some infinite thing.

Socrates was concerned that writing would provide “a recipe not for memory, but for reminder”. We can write all of the post-it notes we want, but if we don’t remember to actually look at the post-it notes they do us no good. The danger is not losing memory, but the ability to remember to remember.

OK Google

In “The Shallows”, Carr also provides interesting insights into the inner workings of the tech giant Google. Google’s original mission statement was, “To organize the world’s information and make it universally accessible and useful.” The warm homepage, spiced up by the occasional adorable doodle, makes Google a lovable organization. However, even in its early days, there was something unnerving about the company. The author George Dyson, on visiting the Googleplex, remarked:

I thought the coziness to be almost overwhelming. Happy golden retrievers running in slow motion though water sprinklers on the lawn. People waving and smiling, toys everywhere in the dark corners. If the devil would come to earth, what would be a better place to hide?

Probably no institution, apart from the government, has as much personal information about us than Google. It uses that data to generate profit through advertising. So why do we trust the company so much? The answer lies in the psychological bias of the human mind. Every aspect of the way Google interacts with users is statistically designed to make them feel a certain way. Carr explains:

Although the design of its web pages may appear simple, even austere, each element has been subjected to exhaustive statistical and psychological research. Using a technique called ‘split A/B testing’, Google continually introduces tiny permutations in the way its sites look and operate, shows different permutations to different sets of users, and then compares how the variations influence the users’ behavior… In one famous trial, the company tested forty-one different shades of blue on its toolbar to see which shade drew the most clicks from visitors.

This extensive psychological research explains why we find Google pleasant and trustworthy. Despite the innocent appearance, however, Google may have an agenda, as recent events have demonstrated.

Refresh

Written in 2009, it is unfortunate that Carr’s warnings were not followed more closely. The Internet is used more now than ever. Facebook memberships have jumped from 300 million to 2 billion (although it is unclear, of course, how many of those users are Russian robot spies). The number of text messages sent by teenagers rose, more modestly, from 2,300 per month to 3, 339 per month. People are still glued to their smart phones, watches and tablets (as demonstrated by Honolulu recently making it illegal to text at crosswalks).

Perhaps the reason Carr’s admonitions have not been headed is that the Internet is an incredibly useful tool. We may not need to check our e-mail thirty or forty times an hour (as one study suggests employees at work do), but e-mail is still very useful. We may not need to send 3,339 text messages a month, but when your car breaks down it is useful to have a phone handy. Finding a balance is essential, and also challenging.

[i] Lewis Mumford, Technics and Civilization

*Words in the “[]” were added by Carr