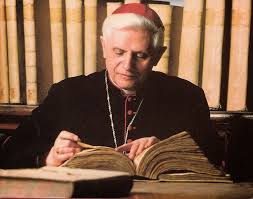

To put the controversy and strife over the recent Motu Proprio into context, I thought a few words from Josef Ratzinger would be helpful. I just finished perusing Dom Alcuin Reid’s 2005 ‘The Organic Development of the Liturgy’ (well worth a read), and in the preface, dated July 26th, 2005 (Saint Anne!), then-Cardinal Ratzinger says the following. It’s almost as if he saw, in some inchoate way, what was coming. I will let his words stand on their own for now, for the reader to ponder:

“At the end of his book, the author enumerates some principles for proper reform: it should keep openness to development and continuity with the Tradition in a proper balance; it should include awareness of an objective liturgical tradition and therefore take care to ensure a substantial continuity. The author then agrees with the Catechism of the Catholic Church in emphasizing that “even the supreme authority in the Church may not change the liturgy arbitrarily, but only in the obedience of faith and with religious respect for the mystery of the liturgy” (CCC 1125). As subsidiary criteria we then encounter the legitimacy of local traditions and the concern for pastoral effectiveness.

From my own personal point of view I should like to give further particular emphasis to some of the criteria for liturgical renewal thus briefly indicated. I will begin with those last two main criteria. It seems to me most important that the Catechism, in mentioning the limitation of the powers of the supreme authority in the Church with regard to reform, recalls to mind what is the essence of the primacy as outlined by the First and Second Vatican Councils: The pope is not an absolute monarch whose will is law; rather, he is the guardian of the authentic Tradition and, thereby, premier guarantor of obedience. He cannot do as he likes, and he is thereby able to oppose those people who, for their part, want to do whatever comes into their head. His rule is not that of arbitrary power, but that of obedience in faith. That is why, with respect to the Liturgy, he has the task of a gardener, not that of a technician who builds new machines and throw the old ones on the junk-pile. The “rite”, that form of celebration and prayer which has ripened in the faith and the life of the Church, is a condensed form of living Tradition in which the sphere using that rite expresses the whole of its faith and its prayer, and thus at the same time the fellowship of generations one with another becomes something we can experience, fellowship with the people who pray before us and after us. Thus the rite is something of benefit that is given to the Church, a living form of paradosis, the handing-on of Tradition.