BENEDICT XVI

GENERAL AUDIENCE

Paul VI Audience Hall

Wednesday, 8 August 2007

Saint Gregory Nazianzus (1)

Dear Brothers and Sisters,

Last Wednesday, I talked about St Basil, a Father of the Church and a great teacher of the faith.

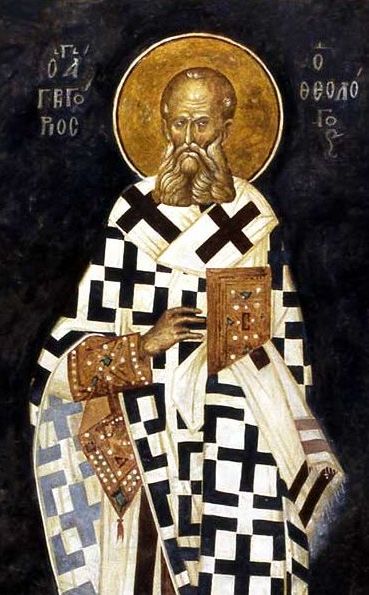

Today, I would like to speak of his friend, Gregory Nazianzus; like Basil, he too was a native of Cappadocia. As a distinguished theologian, orator and champion of the Christian faith in the fourth century, he was famous for his eloquence, and as a poet, he also had a refined and sensitive soul.

Gregory was born into a noble family in about 330 A.D. and his mother consecrated him to God at birth. After his education at home, he attended the most famous schools of his time: he first went to Caesarea in Cappadocia, where he made friends with Basil, the future Bishop of that city, and went on to stay in other capitals of the ancient world, such as Alexandria, Egypt and in particular Athens, where once again he met Basil (cf. Orationes 43: 14-24; SC 384: 146-180).

Remembering this friendship, Gregory was later to write: “Then not only did I feel full of veneration for my great Basil because of the seriousness of his morals and the maturity and wisdom of his speeches, but he induced others who did not yet know him to be like him…. The same eagerness for knowledge motivated us…. This was our competition: not who was first but who allowed the other to be first. It seemed as if we had one soul in two bodies” (Orationes 43: 16, 20; SC 384: 154-156, 164].

These words more or less paint the self-portrait of this noble soul. Yet, one can also imagine how this man, who was powerfully cast beyond earthly values, must have suffered deeply for the things of this world.

On his return home, Gregory received Baptism and developed an inclination for monastic life: solitude as well as philosophical and spiritual meditation fascinated him.

He himself wrote: “Nothing seems to me greater than this: to silence one’s senses, to emerge from the flesh of the world, to withdraw into oneself, no longer to be concerned with human things other than what is strictly necessary; to converse with oneself and with God, to lead a life that transcends the visible; to bear in one’s soul divine images, ever pure, not mingled with earthly or erroneous forms; truly to be a perfect mirror of God and of divine things, and to become so more and more, taking light from light…; to enjoy, in the present hope, the future good, and to converse with angels; to have already left the earth even while continuing to dwell on it, borne aloft by the spirit” (Orationes 2: 7; SC 247: 96).

As he confides in his autobiography (cf. Carmina [historica] 2: 1, 11, De Vita Sua 340-349; PG 37: 1053), he received priestly ordination with a certain reluctance for he knew that he would later have to be a Bishop, to look after others and their affairs, hence, could no longer be absorbed in pure meditation.

However, he subsequently accepted this vocation and took on the pastoral ministry in full obedience, accepting, as often happened to him in his life, to be carried by Providence where he did not wish to go (cf. Jn 21: 18).

In 371, his friend Basil, Bishop of Caesarea, against Gregory’s own wishes, desired to ordain him Bishop of Sasima, a strategically important locality in Cappadocia. Because of various problems, however, he never took possession of it and instead stayed on in the city of Nazianzus.

(To continue reading, please see here).

BENEDICT XVI

GENERAL AUDIENCE

Paul VI Audience Hall

Wednesday, 22 August 2007

Saint Gregory Nazianzus (2)

Dear Brothers and Sisters,

In the course of portraying the great Fathers and Doctors of the Church whom I seek to present in these Catecheses, I spoke last time of St Gregory Nazianzus, a fourth-century Bishop, and today I would like to fill out this portrait of a great teacher. Today, we shall try to understand some of his teachings.

Reflecting on the mission God had entrusted to him, St Gregory Nazianzus concluded: “I was created to ascend even to God with my actions” (Orationes 14, 6 De Pauperum Amore: PG 35, 865).

In fact, he placed his talents as a writer and orator at the service of God and of the Church. He wrote numerous discourses, various homilies and panegyrics, a great many letters and poetic works (almost 18,000 verses!): a truly prodigious output.

He realized that this was the mission that God had entrusted to him: “As a servant of the Word, I adhere to the ministry of the Word; may I never agree to neglect this good. I appreciate this vocation and am thankful for it; I derive more joy from it than from all other things put together” (Orationes 6, 5: SC 405, 134; cf. also Orationes 4, 10).

Nazianzus was a mild man and always sought in his life to bring peace to the Church of his time, torn apart by discord and heresy. He strove with Gospel daring to overcome his own timidity in order to proclaim the truth of the faith.

He felt deeply the yearning to draw close to God, to be united with him. He expressed it in one of his poems in which he writes: “Among the great billows of the sea of life, here and there whipped up by wild winds… one thing alone is dear to me, my only treasure, comfort and oblivion in my struggle, the light of the Blessed Trinity” (Carmina [historica] 2, 1, 15: PG 37, 1250ff.). Thus, Gregory made the light of the Trinity shine forth, defending the faith proclaimed at the Council of Nicea: one God in three persons, equal and distinct – Father, Son and Holy Spirit -, “a triple light gathered into one splendour” (Hymn for Vespers, Carmina [historica] 2, 1, 32: PG 37, 512).

Therefore, Gregory says further, in line with St Paul (I Cor 8: 6): “For us there is one God, the Father, from whom is all; and one Lord, Jesus Christ, through whom is all; and one Holy Spirit, in whom is all (Orationes 39, 12: SC 358, 172).

Gregory gave great prominence to Christ’s full humanity: to redeem man in the totality of his body, soul and spirit, Christ assumed all the elements of human nature, otherwise man would not have been saved.

Disputing the heresy of Apollinaris, who held that Jesus Christ had not assumed a rational mind, Gregory tackled the problem in the light of the mystery of salvation: “What has not been assumed has not been healed” (Ep. 101, 32: SC 208, 50), and if Christ had not been “endowed with a rational mind, how could he have been a man?” (Ep. 101, 34: SC 208, 50). It was precisely our mind and our reason that needed and needs the relationship, the encounter with God in Christ.

(To continue reading, please see here).