How are Catholic couples meant to interpret Amoris Laetitia? When already a fog of confusion surrounds the question of whether or not the divorced and remarried may receive Holy Communion, certain statements in Amoris Laetitia add to the confusion, rather than ministering to Catholic couples with tool of clarity.

Is it right for Catholics to conclusively interpret the document as permitting the divorced and remarried couples to receive communion? May Catholics justifiably denounce the document as being in opposition to Church teaching? If the author of a magisterial document is required to write in light of past Church teaching, utilizing the hermeneutic of continuity, as Pope Emeritus Benedict XVI coins the term in his December 2005 address, interpreters are also required to read the document in light of past Church teaching.

Hence faithful Catholics interpreting Amoris Laetitia must read the document in light of prior Church documents, most especially Pope Saint John Paul II’s rich wealth of writings. John Paul II offers a clear answer on the Church’s approach to dealing with situations of fractured marriages and ruptured family circumstances.

An important message to take from the papal documents is that the Church does not operate as an institution, arbitrarily proscribing moral standards for the faithful to live by. The holy fathers of the past decades are not out to hinder the flourishing of family bonds, as they have been accused of doing, by withholding communion from the divorced and remarried. Rather, the Church has the intent of instructing the faithful concerning the fullness of meaning and the beauty of the sacrament of marriage. The Church teaches that communion must be restricted from the divorced and remarried, if they are living in sin, because of the sacramentality of marriage and because of marriage’s deep theological implications. Pope Francis and John Paul II together show how much aid the Holy Mother Church offers to her children, in terms of gifting them with the graces and assistance necessary to work through every family difficulty, however complex.

The Church takes great care to shield and protect the bond of marriage because of its theological significance. Marriage is a sacrament, elevated above any animalistic reproductive union. As Pope Francis enunciates in his document on the joy of love:

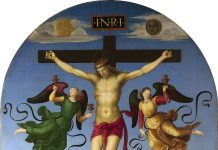

Christian marriage, as a reflection of the union between Christ and His Church, is fully realized in the union between man and woman who gives themselves to each other in a free, faithful, and exclusive love, who belong to each other until death and are open to the transmission of life, and are consecrated by the sacrament, which grants them the grace to become a domestic church and a leaven of new life for society.

Sacraments, according to the Catechism of the Catholic Church (CCC), are “efficacious signs of grace, instituted by Christ and entrusted to the Church, by which divine life is dispensed to us.” Unlike other human relationships, marriage is elevated to the level of a sacrament because it has a signification beyond the temporal world. However, marriage bonds between a man and woman only last a lifetime. The transcendental union of Christ and His Church, which marriage signifies and plays a part in forming, extends into the eternal realm. The marriage is safeguarded as something truly sacred because of the great divine mystery which it is connected with. “As a sacrament of the Church, marriage is by nature indissoluble. As a sacrament of the Church, it is also a word of the Spirit exhorting man and woman to shape their whole life together.”

Ephesians 5:28-31conveys the significance of the meaning of the body in marriage, reflecting the truth of Christ’s Mystical Body. Ephesians 5:28-31 states:

Even so husbands should love their wives as their own bodies. He who loves his wife loves himself. For no man ever hates his own flesh, but nourished and cherishes it, as Christ does the church, because we are members of his body. ‘For this reason a man shall leave his father and mother and be joined to his wife, and the two shall become one’.

Referring to this particular passage, John Paul II comments that “the words of the author of Ephesians…are centred on the body, both in its metaphysical meaning, that is, on the body of Christ which is the Church, and in it concrete meaning, that is, on the human body in its perennial masculinity and femininity, in its perennial destiny for union in marriage.” Part of what defines marriage as a sacrament is that it contains a visible sign of an invisible reality. The body is a visible sign of the Mystical Body of Christ, the Church. The one-flesh union of marriage signifies the unity and oneness of the Mystical Body, as John Paul II indicates: “In this sign – and through this sign – God gives himself to man in his transcendent truth and in his love.” To add to the body’s significance as a sign, John Paul II writes that the sign “does not merely indicate and express grace in a visible way, in the manner of a sign, but produces grace and contributes efficaciously to cause that grace to become part of man and to realize and fulfill the work of salvation in him, the work determined ahead of time by God from eternity and fully revealed in Christ.”

The words in the marriage vows are also outward signs of the sacrament. As John Paul II says, “Marriage as a sacrament is contracted by means of the word, which is a sacramental sign in virtue of its content, ‘I take you as my wife/as my husband, and I promise to be faithful to you always, in joy and in sorrow, in sickness and in health, and to love you and honour you all the days of my life.’” The vows in marriage are physical signs of the indissolubility of marriage. This sign of marriage signifies and causes in each person an indissoluble bond to form and strengthen between not only the two spouses, but also between God and each spouse. Each spouse is meant to become closer in unity with God through becoming a gift-of-self to the other. As John Paul II enunciates, “the point [of marriage] is not only to transmit the ‘good news’ of salvation, but to begin at the same time the work of salvation.” Marriage, thus, is a sacrament because it is a visible sign of an invisible reality, causing the grace, including the indissoluble bond, that it signifies.

The “language of the body” instituted from the beginning of man’s existence, reread, speaks of man’s redemptive meaning and final purpose of union with God. “Man…is able, on the basis of the ‘language of the body’ reread in the truth, to constitute the sacramental sign of conjugal love, faithfulness, integrity, and this as an enduring sign.” Man, as a creature elevated above the rest of creation, is made for union with God. The spousal union between man and woman, indissoluble, reflects the indissoluble covenant which man has with God, through man’s nuptial meaning. As expressed by John Paul II, “on the background of the words spoken by the ministers of the sacrament of Marriage, there stands the perennial ‘language of the body,’ to which God Himself ‘gave its beginning’ by creating man male and female: a language that was renewed by Christ.” In his use of the term, “language of the body,” John Paul II implies that man is, by his very nature, created to be joined to God. This union between man and God is symbolized by the indissolubility of the human covenant of marriage. Christ redeemed man, renewing the covenant with man that man had been unfaithful to. Christ also exemplified perfectly to man the way in which he might become united with God unto eternity. John Paul II teaches illustrates that the covenant between God and man is reflected in the marriage covenant:

Christ affirms that marriage – the sacrament of the origins of man in the visible temporal world – does not belong to the eschatological reality of the ‘future world.’ Nevertheless, the man who is called to participate in this eschatological future through the resurrection of the body is the same man, male and female, whose origin in the visible and temporal world is linked with marriage as the primordial sacrament of the very mystery of creation.

John Paul II also notes that the “sacramental word is, of itself, only a sign of the coming to be of marriage. And the coming to be of marriage is distinct from its consummation, so much so that without this consummation, marriage is not yet constituted in its full reality.” Marriage is not just the stating of vows, nor is the sacrament entirely completed upon the first conjugal act. Rather, marriage is continually renewed and continually signifies a deeper theological reality, throughout a lifetime. Marriage signifies the unbreakable union between Christ and His Church. For this reason, the covenant between a man and woman is meant to be witnessed and sanctioned by the Church; marriage is sanctified above a mere physical union.

The fact that man and woman are given the immense gift of partaking in creation through the conjugal union shows also how very significant the sign of marriage is. God elevated man to such a degree that man, as male and female, was permitted to participate in God’s operation of creating new human beings. “Based on the mystery of redemption, a particular gift, that is, grace, corresponds to marriage.” Marriage and procreation is therefore, in this manner also, a sign of man’s likeness to God.

The sacramentality of marriage and the theological meaning of the conjugal union takes precedence in Christ’s response to the Pharisees in Matthew 19:3, when they ask Him whether it is lawful for a man to divorce his wife. Jesus responds, “Have you not read that from the beginning the Creator created them male and female and said, ‘For this reason a man will leave his father and his mother and unite with his wife, and the two shall be one flesh?’ So it is that they are no longer two, but one single flesh. Therefore what God has joined let man not separate” (Matthew 19:4-6). Christ says further: “therefore I say to you: Whoever divorces his wife, except in the case of concubinage, and marries another commits adultery” (Matthew 19:8-9). Also: “the one who marries a woman divorced by her husband commits adultery” (Matthew 5:32). This teaching of Christ’s ties in with Ephesians 5, to reveal that marriage is indissoluble because of its theological implications.

With the background of Scripture and his audiences on the theology of the body, John Paul II writes in his apostolic exhortation, Familiaris Consortio: “Marriage between two baptized persons is a real symbol of the union of Christ and the Church, which is not a temporary or ‘trial’ union but one which is eternally faithful. Therefore between two baptized persons there can exist only an indissoluble marriage.”

In a section of the document specifically directed to the divorced and remarried, John Paul II adds:

The church, which was set up to lead to salvation all people and especially the baptized, cannot abandon to their own devices those who have been previously bound by sacramental marriage and who have attempted a second marriage. The Church will therefore make untiring efforts to put at their disposal her means of salvation.

The above quotation is later affirmed by Pope Francis in Amoris Laetitia 305, although Amoris Laetitia makes a much more vague and ambiguous statement on the matter.

Within the following paragraph, John Paul II exhorts pastors and “the whole community of the faithful”:

…to help the divorced, and with solicitous care to make sure that they do not consider themselves as separated from the Church, for a baptized person they can, and indeed must, share in her life. They should be encouraged to listen to the word of God, to attend the Sacrifice of the Mass, to persevere in prayer, to contribute to works of charity and to community efforts in favour of justice, to bring up their children in the Christian faith, to cultivate the spirit and practice of penance and thus implore, day by day, God’s grace.

John Paul II’s teaching is so very clear and definitive on the delicate subject, that it would seem inappropriate even to paraphrase his statement, which is firm and clear so that it can be taken with no admixture of error:

The Church reaffirms her practice, which is based upon Sacred Scripture, of not admitting to Eucharistic Communion divorced person who have been remarried. They are unable to be admitted thereto from the fact that their state and condition in life objectively contradict that union of live between Christ and the Church which is signified and effected by the Eucharist. Besides this, there is another special pastoral reason: if these people were admitted to the Eucharist, the faithful would be led into error and confusion regarding the Church’s teaching about the indissolubility of marriage.

John Paul II thus makes evident that the Church never abandons her flock, but always tends to it diligently, safeguarding the treasured sign and sacrament of matrimony. John Paul II goes on to reveal the mothering nature of the Church by encouraging those in a situation of divorce and remarriage to hasten to reconciliation, where they might receive the merciful forgiveness which the Church provides:

Reconciliation in the sacrament of Penance which would open the way to the Eucharist, can only be granted to those who, repenting of having broken the sign of the Covenant and of fidelity to Christ, are sincerely ready to undertake a way of life that is no longer in contradiction to the indissolubility of marriage.

Finally, John Paul II concludes his apostolic exhortation with:

By acting in this way, the Church professes her own fidelity to Christ and to His truth. At the same time she shows motherly concern for these children of hers, especially those who, through no fault of their own, have been abandoned by their legitimate partner.

With this immense background of teaching, laid out with precision, clarity, and beauty by John Paul II, Catholics can read and understand with confidence what teachings the Magisterium has put forth on the matter of distributing communion to the divorced and remarried. Thus, when we read, for example, paragraph 305 in Amoris Laetitia, which entails some ambiguity and grounds for debate, we may know what the standpoint of the Church is, by referring backward and comparing sources, utilizing the hermeneutic of continuity. Amoris Laetitia 305 states: “because of forms of conditioning and mitigating factors, it is possible that in an objective situation of sin – which may not be subjectively culpable, or fully such – a person can be living in God’s grace, can love and also grow in the life of grace and charity, while receiving the Church’s help to this end.” Footnote 351, accompanying this phrase, further states somewhat ambiguously:

In certain cases, this can include the help of the sacraments. Hence, “I want to remind priests that the confessional must not be a torture chamber, but rather an encounter with the Lord’s mercy.” I would also point out that the Eucharist “is not a prize for the perfect, but a powerful medicine and nourishment for the weak.”

This quotation, although ambiguous on its own, when taken in context of John Paul II’s prior teachings merely affirms that a person, coming from a situation of divorce and remarriage, might receive communion after making a worthy confession and amending his/her family situation. The Church has always taught and always will teach that the divorced and remarried must be reconciled to the Church and to God, and must amend their marital situations before receiving communion, due to the indissolubility of the sacrament of marriage and its deep theological connection to each baptized individual’s covenant with God.

Works Cited

Pope John Paul II. “Man and Woman He Created Them”. Boston: Daughters of St. Paul, 2006.

Pope John Paul II. “Familiaris Consortio”. Vatican Library, 1981.

Pope Francis. “Amoris Laetitia”. Vatican Library, 2016 .