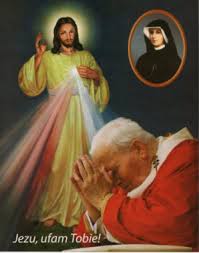

(The following is an address I offered yesterday at Saint Hedwig’s Church for the Divine Mercy celebration. Editor)

This being the Year of Mercy, decreed by Pope Francis, as well as Divine Mercy Sunday, as decreed by Pope Saint John Paul II, back in 2000, I thought that I had better not stray too far in these few moments of reflection from the theme of mercy, but here I would like to briefly connect mercy with truth.

We hear much of mercy, which in its Latin original is derived from miser (sad) and cordia (heart). In his one question in the Summa on mercy, Saint Thomas Aquinas states that mercy derives from our being moved with pity at the sight of another’s suffering, to feel compassion for them, with a desire to alleviate whatever evil is afflicting them. This mercy is all the more intense the more we fell connected to the other, to the point even of feeling the sadness as our very own.

So far so good, but there are two things to be warned of in mercy, the first from Thomas, the other from my own ponderings.

First, to Thomas, who says that mercy is first a passion, and thus blind and uncontrolled. Many things ‘move’ us, especially as our vision expands over the internet with news of almost unbelievable suffering across our world. Our pity must therefore be guided and moderated by reason, otherwise we may be overwhelmed by misery, or act irrationally.

Upon whom, how, in what way, should we show mercy? Like contrition (which is sorrow for our own moral evil), we must feel pity for the other in the right way, the right amount, and for the right kind of evil. We pity the victims more than the suicide bomber who killed them. Is this mercy? Who deserves our pity more? Do we pity the misguided politician who votes for abortion and same-sex marriage, or the children deformed or even destroyed by these laws?

The answer, or at least part of it, can be found in the connection between mercy and charity, or love. In fact, mercy may be defined as ‘charity put into action’. Mercy is not mercy unless we do something, act upon our pity, alleviate the suffering of the other in some way. In his meditation on suffering Salvifici Doloris, Pope John Paul II invokes the parable of the Good Samaritan as the most perfect example of mercy, the Samaritan being a type of Christ who, in his early encyclical Dives in Misericordia, promulgated two years after he became Pope, John Paul described as the very face, the Incarnation, of the mercy of the Father which, like Christ, we must put into effect. As he writes,

It is precisely the mode and sphere in which love manifests itself that in biblical language is called “mercy.” (#3)

It is Christ Who teaches us what ‘true’ mercy means, which brings me to the essential point: Mercy must be connected to, and founded upon, truth. There are few things worse than misguided mercy, pitying those who perhaps need little or none, while being merciless to those who need it most. We campaign for ‘animal rights’, and even the rights of ‘mother Earth’, while murdering the unborn, and now we consider it a ‘mercy’ to put the old and the sick out of their own misery.

Quid est veritas, Pilate asked of Christ during His trial, ‘what is truth’, without realizing that Truth Himself was standing before him. Christ gave no answer, perhaps since, like so many in our modern world, Pilate would not have listened, was not ready to hear.

Truth is, as Saint Thomas states, an adequatio rei et intellectus, an adequation between the mind and reality. When the mind is truly conformed to how things really are, then there is truth.

Our mercy must be founded on the truth of things as they are. Although mercy may and should go beyond justice, the strict level of ‘what one is owed’, it must never violate or contravene justice. To pervert justice is to pervert mercy, to make it false. We should show mercy and pity where they are due, where the suffering is ‘real’, is true, and where can alleviate the suffering with goodness and truth.

I will close with three conclusions from these principles:

First, the main suffering in our world is not material, but spiritual. As the prophet Hosea lamented, ‘my people perish for lack of truth!’, and Bd. Mother Theresa said that spiritual poverty was far more rampant, and far worse, than the material variety. Indeed, in Salvifici Doloris, his meditation on suffering, Pope John Paul declared that every physical evil could be traced back to some kind of moral evil. That is why our mercy should primarily be directed towards those who know not the truth, by giving them the truth. This will not be easy, but we must open ourselves to the parrehsia, the boldness, spoken of by Saint Paul. We must stand up for truth, proclaim it, discuss it with our family and friends, and fear not the consequences, to bring them to conversion:

Conversion is the most concrete expression of the working of love and of the presence of mercy in the human world. The true and proper meaning of mercy does not consist only in looking, however penetratingly and compassionately, at moral, physical or material evil: mercy is manifested in its true and proper aspect when it restores to value, promotes and draws good from all the forms of evil existing in the world and in man. Understood in this way, mercy constitutes the fundamental content of the messianic message of Christ and the constitutive power of His mission. (Dives, #6)

Second, we must be converted the truth found in Christ and the Church He founded. We must learn this truth, make it our own, for only in the truth can we show true, and not false, mercy to others: Human life is inviolable, marriage is indissoluble, (and, need we add, only between a man and a woman), euthanasia and abortion are grave evils equivalent to murder. Even if we cannot work out all the arguments for these truths, we accept them on the authority of Christ himself. And, to bring this back to the first point, John Paul II will later say in Evangelium Vitae that all the heinous crimes against life, ‘ do more harm to those who practise them than to those who suffer from the injury. Moreover, they are a supreme dishonour to the Creator more harm is done” (E.V. #3).

Third, therefore, we must distinguish mercy from tolerance and false compassion: To have mercy on someone does not mean allowing them to wallow in evil. It is a misconception that good and evil are subjective, or not even real. God is a merciful God, but He is also just, and even His mercy cannot violate His justice. There is a requirement to going to heaven: keeping the commandments, loving God and neighbour, being in a ‘state of grace’, which means in a right relationship with God. Without these, we are lost. As Christ declares, and Saint Paul specifies, the immoral and unrepentant cannot inherit the kingdom of God, unless they repent.

Again, to Pope John Paul:

one cannot fail to be worried by the decline of many fundamental values, which constitute an unquestionable good not only for Christian morality but simply for human morality, for moral culture: these values include respect for human life from the moment of conception, respect for marriage in its indissoluble unity, and respect for the stability of the family. Moral permissiveness strikes especially at this most sensitive sphere of life and society. Hand in hand with this go the crisis of truth in human relationships, lack of responsibility for what one says, the purely utilitarian relationship between individual and individual, the loss of a sense of the authentic common good and the ease with which this good is alienated. Finally, there is the “desacralization” that often turns into “dehumanization”: the individual and the society for whom nothing is “sacred” suffer moral decay, in spite of appearances. (Dives, #12)

It is no ‘mercy’ to leave adulterers, fornicators, homosexuals, those involved in abortion or contraception, nor even unbelievers, agnostics, to remain in their objectively sinful states, thinking they are ‘fine’ and in ‘good graces with God and His Church’. That is a scandal, for how is that seeking their good in the truth? In a recent and very rare interview last October, Pope Emeritus Benedict lamented that one of the primary errors of our modern era is a sense that we can achieve mercy without repentance, which means, without an awareness of the truth of our own sinfulness and need for conversion. The Pope emeritus asks,

whether modern man is waiting for a “mercy” that requires anything of him—no restoration of truth, no penance, no “works”, as it were. This restriction is precisely the “limit” of mercy, the line where mercy is understood to deny justice, rather than the healing of his soul through its acknowledgment.

This applies, of course, also to us. Without acknowledging our own ‘violations of justice’, our sinfulness, and dependence upon God, we will wallow in our own self-centredness, and exclude ourselves from the kingdom of heaven. But we must not only impress this truth upon ourselves, in our daily prayer, our examination of conscience, how we think of and treat others in our mundane tasks. More, we must also teach these truths to others. As Vatican II declares, quoted in the Catechism

“The witness of life, however, is not the sole element in the apostolate; the true apostle is on the lookout for occasions of announcing Christ by word, either to unbelievers…or to the faithful.” (CCC, #905; cf., AA 6.3).

Not an easy task, but we must remind ourselves that this year of mercy is not a year of unconditional forgiveness, but an opportunity to seek forgiveness, especially at this critical moment of human history which even the usually restrained Pope John Paul saw standing on the brink of a ‘new flood like Noah’, unless we repent. We must pray also for others to do the same (especially by the Mass, the Rosary and the Divine Mercy), for the healing of their and our souls, that all may return to the Father like the Prodigal son. For the son had to ‘come to his senses’, to see the truth in his condition, and make the journey back to the ‘good things’ of his father’s house. All he had to do was take that first step: We can be sure that the Father will meet us along the way, with robe and ring in hand, ready to prepare a banquet for us.

As Pope Francis declared on this Sunday three years ago soon after his pontificate began:

I am always struck when I reread the parable of the merciful Father. … The Father, with patience, love, hope and mercy, had never for a second stopped thinking about [his wayward son], and as soon as he sees him still far off, he runs out to meet him and embraces him with tenderness, the tenderness of God, without a word of reproach. … God is always waiting for us, He never grows tired. Jesus shows us this merciful patience of God so that we can regain confidence and hope — always! (Homily from Divine Mercy Sunday, 2013)

To conclude with the great hopeful words of Pope John Paul, there is only thing that can block this path to eternal salvation:

On the part of man only a lack of good will can limit (God’s mercy), a lack of readiness to be converted and to repent, in other words persistence in obstinacy, opposing grace and truth, especially in the face of the witness of the cross and resurrection of Christ. (Dives, #13)

We must be like the ‘good thief’, who, even at the very last moment, end opened himself to the grace of God, as offered to Him through His Son, Jesus Christ.

Amen to that.