A bread oven is simply a dry hollow pile of mud and straw in which a fire is built. When the fire dies down, the hot mud bakes whatever is put into it, whether bread, vegetables, or meat. It is a technology that has pre-historic origins and follows a common pattern across continents: the bread ovens of Africa, the Native American Hornos, and most important for us, the clay ovens of French Canada. Curiously, I cannot find any rural tradition for clay ovens in British history. It appears that the industrial revolution, which began there, has almost completely destroyed any historical connection with such a timeless technology.

This bread oven used to be the centre of the domestic church, the source of sustenance for the life of the family. When real bread has been held, the words of the gospel make sense: what Father would give his son a stone when he asked for bread. Real bread looks like a stone. The force of the comparison is lost when we only experience modern factory bread. The domestic oven is a homely tabernacle, a place where bread is made so that natural life is sustained.

Of course, we do not live by bread alone. Indeed, as human beings we have mouths so that we may sustain our life by receiving the Body of Christ in the Mass. Nevertheless, it is no accident that those cultures which observe the domestic traditions have a lively Catholic Faith, for the logic and lessons of Humane Vitae are written in the hearts of those who live with real things and eat real food.

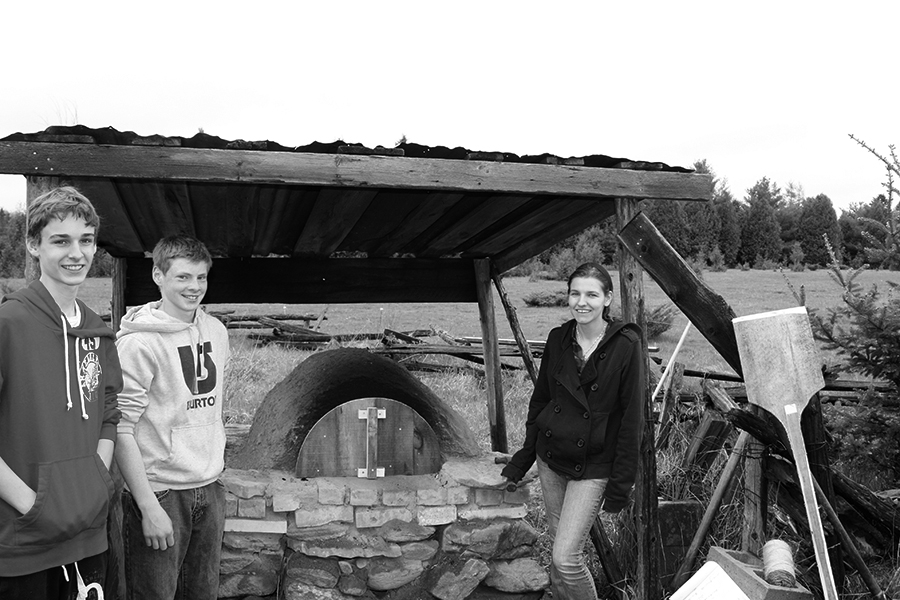

Making a bread oven is simple. This one was built as a high school project with Wayside Academy, but I have built them as home-school projects as well. First one must gather rocks into a pile and then place some flat rocks on the top as the hearth. This process evokes the actions of St. Francis of Assisi, who began his rebuilding of the Church one rock at a time. On the top of the flat rock base, a frame of willow branches is tied up using cotton twine, like a rounded stick igloo, abut the size of a bushel basket. These form the ribs of the oven, a natural representation of the ribs taken from Adam and surrounded by clay to form Eve. Indeed, we even do this part, mixing clay and dried straw or grass with water, to be formed by hand into wet odd-shaped bricks.

There is no reason to worry about what kind of clay to use. The desire for perfection in materials is a modern industrial fiction. The best clay to use is that which is available. That is the evidence from folk wisdom embodied in the traditional trades all over the world. Clay that is near at hand is better than the clay that must be carried. To find the best clay, simply dig about two feet down. The stuff found there will almost always be sufficient for the task.

The wet clay bricks are piled around the sides of the willow frame a couple of rows at a time and allowed to set for a few hours so they will not sag. The opening is about sixteen inches wide, or the length of the arm from the elbow to the first knuckle. An old wheel rim is a perfect form for this. The opening must be about two-thirds the height of the top of the oven. When the whole is complete, it dries for a week (the time of creation) and then the first small fire is set inside it, the smoke billowing out the front. Several of these fires harden the clay. The oven is finished by adding a door of hardwood with some steel roofing nailed to it.

To make bread, we begin with wheat, a grain that has been cultivated from the time when humans first took up agriculture. Our wheat today is not like the old-fashioned wheat of yesteryear. Red Fife wheat, the Ontario miracle that made the new world prairies so productive, is now a heritage breed. Our modern wheat is a genetically modified thing, milled by steel rollers to produce perhaps the most unlovely of all food: modern, indestructible, unrottable, unmouldable, tasteless bread—a matrix for processed spreads and unidentifiable meats.

Real wheat from the hand of God grows in soil made of clay, organic matter, and manure. It locks up the sunlight as carbohydrate in its grains. These grains are coated with life, plants we scientifically identify as yeast but which used to be called leaven. This combination of wheat and leaven is crushed and pounded by rocks, in much the same process that produced the soil itself by grinding rocks into fine sand over the ages. The resultant flour is mixed with water, which is essential to all life, and placed into the clay oven and fired by dried sticks. The heat from the fire is simply a sudden release of the very sunlight that pulled the wheat out of the ground. This heat is absorbed by the clay to bake the dough into usable forms.

When we eat this bread, we are eating sunlight stored in grain made palatable for us by sunlight stored in wood. Food is grown and cooked in clay with the nutrients provided by manure, so that literally stones are turned into bread for us by the sun. And doing this, we reach back across time to a technology that predates iron and bronze. We are there with the first peasants, our first parents, and we share this technology with the remaining peasantry that still exists across the world.

The fuel is twigs or sticks gathered from the ground under the trees on any street, sticks that are now put out for trash. These can be used to cook with. When the fire dies down, rake the glowing coals into a pail of water. When dried out, these can be used as charcoal for the barbecue. It took the class about two days to complete the oven, a day to fire it and, the next morning, a few hours to mix the dough, fire the oven, and bake bread in time for lunch.