Arguably the most popular painting in the Western World is The Last Supper, and virtually every educated person knows that it was painted by Leonardo da Vinci. The precise electrifying moment of the meal is rendered as Jesus tells the Apostles that one of them will betray him, and they all glare at him and at each other in utter disbelief. But whether Leonardo was ever a devout Catholic is left more to our speculation than to any proof. He disliked monks, but he never spoke out against religion. His apparent lack of interest or involvement in religious matters throughout his life provokes us to question the powerful representation of betrayal in The Last Supper. Was Leonardo subconsciously working through his own doubts and strayings from the faith into which he was born and baptized? Or did he merely take a commission from Duke Ludovico Sforza to paint the picture for money? Walter Pater believed that Leonardo held philosophy to be above religion, and that he did not take very seriously the doctrines of Christianity. But whatever reservations Leonardo had about his faith when his health was good, they were dispelled during the last months of his life. His biographer Giorgio Vasari noted that, “Finally, being old, he lay sick for many months. When he found himself near death he made every effort to acquaint himself with the doctrine of Catholic ritual.” Before his death he received the Sacraments and in his will he left instructions for dozens of solemn Masses to be said at four different churches.

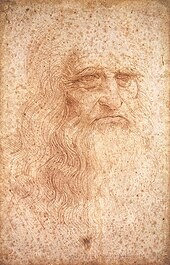

Leonardo was born out of wedlock to Ser Piero, a notary, and a peasant woman named Caterina. Perhaps because nature had enormously gifted him with intellect and imagination, he was largely self-taught and enjoyed the good luck to have been born near Florence, where a genius was apt to meet and be inspired by kindred spirits. Yet, like Michelangelo, he was a solitary genius who never married and seemed to have few friends, though in appearance and manners he was far more agreeable than his younger rival for fame. Early in youth apprenticed to the Florentine painter Verrocchio, Leonardo soon surpassed his teacher by knowing instinctively more than Verrocchio had been able to teach. By studying the full panoply of his works, except in only several instances it may be said that Leonardo, unlike Michelangelo, refused to be influenced by the classic works of antiquity and was therefore the true forerunner of the modernist movement in painting.

Ludovico il Moro of Milan became the most famous and powerful tyrant of his age. Leonardo, nearly thirty and apparently eager to advance himself, wrote a characteristic letter to the cruel prince cataloging his own talents:

I have a process for constructing very light, portable bridges, for the pursuit of the enemy; others more solid, which will resist fire and assault and may be easily set in place and taken to pieces. I also know ways of burning and destroying those of the enemy. . . I can also construct a very manageable piece of artillery which projects inflammable materials, causing great damage to the enemy and also great terror because of the smoke . . . Where the use of cannon is impracticable I can replace them with catapults and engines for casting shafts with wonderful and hitherto unknown effect; briefly, whatever the circumstances I can contrive countless methods of attack. In the event of a naval battle I have numerous engines of great power both for attack and defense: vessels which are proof against the hottest fire, powder or steam. In times of peace I believe that I can equal anyone in architecture, whether for the building of public or private monuments. I sculpture in marble, bronze and terra cotta; in painting I can do what another can do, it matters not who he may be. Moreover I pledge myself to execute a bronze horse to the eternal memory of your father and the very illustrious House of Sforza, and if any of the above things seem impracticable or impossible I offer to give a test of it in your Excellency’s park or in any other place pleasing to your lordship, to whom I commend myself in all humility.”

The letter worked; soon Leonardo was employed by the prince and busy painting the portrait of the prince’s mistress, Cecilia Gallerani. After The Last Supper Leonardo’s most ambitious work in Milan must have been the “bronze horse” for which he had made a plaster model which was destroyed when the French arrived in Florence and drove the duke from power. Had the statue been completed, based on preliminary drawings which did survive, it may have rivaled Michelangelo’s David since Leonardo’s mastery of the anatomy of the horse was probably equal to Michelangelo’s expert knowledge of human anatomy.

The artistic competition between Leonardo and Michelangelo has fascinated historians and they rarely fail to explore it. Though a talented sculptor, Leonardo did nothing to match the Pietà and the David of Michelangelo. Perhaps his obvious limitations sparked his own curiously inept way of explaining his preference for art over sculpture:

I do not find any difference between painting and sculpture except this: the sculptor pursues his work with great physical effort, and the painter pursues his with greater mental effort.

Michelangelo might have answered by asking himself which was the more difficult task, chipping away at marble and bronze or painting the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel.

No longer employed by the duke, Leonardo offered his services to Caesar Borgia and became a military engineer in his Romagna campaign. When Borgia in turn fell, Leonardo began to move about the cities of Italy in search of a patron … Florence, Milan and Rome. Some of the paintings done during this period were lost or destroyed, and we know about them only by the testimony of those who greatly admired them. Other works survived but were damaged or not well protected or tampered with by inferior artists. The Mona Lisa, completed in 1507 when Leonardo was in his mid-fifties, is likely the second most famous painting in the world and the favorite of Leonardo’s works. We do not know who modeled for the enigmatic painting of the serene and beautiful smiling lady, but we do know that it was enormously popular in its time. Leonardo was reluctant to part with it, but finally sold it for four thousand gold crowns to the King of France. In a later century Napoleon took possession of the lovely lady and used her to decorate his bedroom.

In his last years Leonardo left Italy for France at the invitation of King Francis I and never returned. From this last period we have his masterful St. Jerome in the Desert (1514). Perhaps he saw something of the arc of his own life in St. Jerome as he finally came to a quiet and restful place in the Château of Cloux near Amboise. His powers declined gradually and the King of France provided him a generous pension while he contemplated the problem of building canals and managing the flow of the Loire River.

The great legacy of Leonardo is not just artistic. He mastered the sciences as well, and fused his mastery of art and science by conceiving of things to be created that would remain dormant in human history for hundreds of years to come. He formulated seminal notions for future fields such as geology and botany. He knew the earth was much older than the Bible had said it was, and that fossils were the proof of it. He pioneered the steam engine and actually created a steam cannon. He laid down basic principles for the science of aviation and studied the flight of birds with amazing accuracy. He even designed an underwater diving suit. All of these genius-at-work discoveries, however, were concealed from history for centuries by the fact that he jealously composed his notes in a code ultimately revealed as readable merely by holding the notes up to a mirror.

One of the great tragedies of history is that so many of Leonardo’s works were left unfinished. Did he find them so often far from ideal that they were not worth the effort to bring them closer? We end by asking the question Sigmund Freud asked about Leonardo … always looking at a man’s childhood to find the flaws that plague him in later life. When Leonardo’s father abandoned him in early life, was that why Leonardo so often abandoned his own “children”?

From the Pen of Leonardo da Vinci

Art is never finished, only abandoned.

For once you have tasted flight you will walk the earth with your eyes turned skywards, for there you have been and there you will long to return.

He who wishes to be rich in a day will be hanged in a year.

I have offended God and mankind because my work didn’t reach the quality it should have.

Life is pretty simple: You do some stuff. Most fails. Some works. You do more of what works. If it works big, others quickly copy it. Then you do something else. The trick is the doing something else.

In rivers, the water that you touch is the last of what has passed and the first of that which comes; so with present time.

Nothing strengthens authority so much as silence.

Our life is made by the death of others.

The greatest deception men suffer is from their own opinions.

The poet ranks far below the painter in the representation of visible things, and far below the musician in that of invisible things.

There are three classes of people: those who see, those who see when they are shown, those who do not see.

Where there is shouting, there is no true knowledge.

While I thought that I was learning how to live, I have been learning how to die.