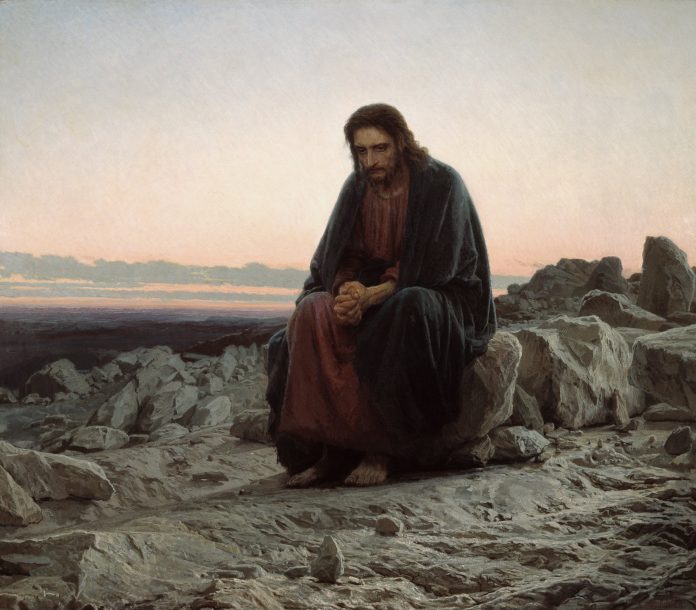

Can there be a shorter account of Our Lord’s forty days in the desert than the one from Saint Mark? It omits not only the familiar three temptations but also the fact that Jesus fasted for the entire period of nearly six weeks. In doing so, he matched the great prophets from the Old Testament—Moses and Elijah—who had themselves gone without food for forty days and forty nights. This omission is insignificant for us, because nobody fasts nowadays. And yet fasting is recommended by both Scripture and Tradition. To take only one instance, Jesus said of his disciples—and that includes us—“The days will come, when the bridegroom is taken away from them, and then they will fast in that day.”[1] And fasting, severe fasting, has been an essential element of Lent until fairly recently. Have you ever wondered why pancakes are a traditional meal for Shrove Tuesday, alias mardi gras, the day before Lent begins? It’s because they are cooked in lard, and, in the past, the housewife had to use it up before Ash Wednesday; there was no meat or meat product, such as lard or broth, served until Easter Sunday.

Nowadays, given that the fast has been reduced to vanishing point, how are we to meet the demand to observe that abstinence affirmed by both Scripture and Tradition? Well, our fasting must take another form, translating into contemporary terms the practices of the past. We can do so by examining the psychology of fasting. It provides an insight into our Catholic mentality, what could be called the Catholic approach to becoming a saint, which is, after all, the goal that each of us dedicates himself to by being baptized. Our spirituality is based on the premise that with practice one can become holy. The principle can be succinctly expressed: one imitates the external symptoms of a certain spiritual state in order to internalize it. For example, every serious Christian will want to keep the Sabbath holy, which for Catholics means attending Mass. The obligation is therefore a constraint only for the person who has not spiritually mature enough to want this essential element of our religion. But by obeying the commandment, one gradually develops an understanding of the importance of participating in public worship every Sunday.

What then is the attitude that should make someone want to fast and which, according to our Catholic approach, we try to attain by actually fasting? Think of situations where the very idea of eating is distressing. They are three of them. The first is severe grief. When someone has died, for instance, kind neighbours will bring food to the home of the deceased, knowing that the family is likely to neglect eating at such a time. Secondly, illness can take away one’s appetite. And thirdly, people may forget to eat when they are engrossed in some activity: a moment of inspiration for a writer or composer, for example, or a scientist struggling to solve an anomaly in his observations, or sometimes even a boy or girl doing homework or—more likely—on facebook or some other electronic perversity.

Each of these has its parallel in Lenten fasting. The first one—grief—describes the Christian whose meditation on the suffering and death of Christ is so intense that he shares the sorrow of Our Lady at the foot of the cross. Someone we love has died, and died for us. Although we may not grieve to the extent that we should, our acting as if we did by fasting is a means of keeping Christ’s sacrifice alive in our minds. The second reason for fasting—illness—is something like the mental state of a Christian who has become aware of the heinousness of sin. If we could see even minor sins for the evil they are, we would be in such great distress that the thought of food would be unbearable. Few of us, alas, have that sensitivity, but by a sort of holy pretence we imitate the symptoms of a saint in order to approach his sanctity. And to the third—being lost in thought—corresponds the attention we learn to give to the things of God. Again, I suppose none of us would claim to have attained that degree of holiness, but we can move towards it by developing and interest in our faith. You could, for instance, read the life of a saint or open your Bible from time to time.

There is thus an element in common among all of these reasons for fasting; each creates a vacuum, a condition that the spirit as well as nature abhors. That sort of vacuum will not come about as a result of the minimal physical fast required of Catholics today, limited to Ash Wednesday and Good Friday, but there are other forms of fasting that will serve as well. In Canada today, entertainment is the “food” on which we glut ourselves. Modern fasting, therefore, will achieve its goal if we make space for God by reducing or even eliminating pastimes that contribute little or nothing to our spiritual development. Consider the internet, for instance. Honestly now, what would be lost by limiting its use to, say, the news? If your answer is not “Nothing would be lost,” I would say, “You have an addiction.” Why not turn off the cellphone from time to time? As well, why not ration or eliminate your viewing of movies? And what about computer games or surfing the net, which is at best a waste of time and at worst an occasion of sin? Give some thought to how you spend your leisure time, and arrange your programme of “fasting” accordingly. If you are serious about your faith you can say every day, “This is the acceptable time, this is the day of salvation.”[2] And let me also add a word of caution about the effect of any form of fasting, from the internet as well as from the table. Anyone who has fasted from food and drink will tell you that there are unexpected mental and physical side effects. We are psychosomatic unities, so that what happens to the body has it effect on the mind, and vice-versa. Hence the weakness and lassitude, which rob the faster of his physical energy, have a psychological parallel in a weakening of the powers of the will and intellect. In other words, fasting from food can make a person irritable and an easy prey to temptations of all sorts. It’s as if the walls around a city suddenly collapsed, leaving it at the mercy of the enemy. The sort of fasting I am suggesting—namely, reducing or eliminating use of the media—will also have its effect, physical as well as psychological.

The point is that the spirit as well as nature abhors a vacuum. The time released by your fasts must filled with something. Otherwise, you will lose rather than gain ground it in your spiritual journey. Recall the words of Jesus:

When the unclean spirit has gone out of a man, he passes through waterless places seeking rest, but he finds none. Then he says, `I will return to my house from which I came.’ And when he comes he finds it empty, swept and put in order. Then he goes and brings with him seven other spirits more evil than himself, and they enter and dwell there; and the last state of that man becomes worse than the first.[3]

With what will you fill the space created by your fasting? In the Bible, prayer and almsgiving are the traditional practices that accompany fasting. And thus, you should resolve to be more prayful and more generous for the next six weeks. Don’t be surprised, therefore, if you find it difficult to persevere in your good intentions; nothing worthwhile is attained without effort, and you may well stagger and even fall. But take heart. You are not the first or the last to experience these difficulties. Centuries ago, the monks of the Egyptian desert experienced them, but they also knew what to do about them. Once an aspiring young monk asked his spiritual father how he had become so holy. He received the following answer:

“I fall down, and I get up again. Then I fall again and get up. And again. That is the secret of holiness.”

[1] Mark 2.20.

[2] 2 Cor. 6.2.

[3] Matt 12.43-45.