Many years ago, I attended an academic talk that left a lasting impression – more so for my reaction to it than for its content. I don’t remember the specifics of the talk, but it advanced a rather sweeping critique and condemnation of modernity in all its aspects – give or take a few. The speaker told us what was wrong with the modern world, something like: it is too utilitarian, functionalist, individualistic, and relativistic.

I was fond of such talks back then; I still am. I’ve heard many. Indeed, I’ve given a few myself. I was also fond of the speaker. He was intelligent and relatively well-spoken, if not a little hyperbolic for my liking. Although his case was, in addition, too secular, I almost entirely agreed with the substance of his presentation. The presumption to diagnose and explain all the sins of the modern world in a mere hour was, of course, unreasonable, but the speaker’s critique was on balance correct.

During the question period, a young audience member asked whether the speaker’s position could be applied to university education and whether a solution to the apparent excessive functionalism of advanced learning, which focuses on gaining useful knowledge and practical skills, might lie in leisure. The speaker’s answer was simple and brief: yes.

I was outraged. Here I was, a young academic who had worked very hard to achieve relatively little success. The life of the mind didn’t come easily to me, nor was it encouraged by my family or friends, all of whom were too practical to think of my studies as anything other than a meal ticket – if that. Worse yet, I looked around me and saw hard work admired less than it had been before, if not altogether disparaged. I saw it everywhere, but particularly in the academy, where it appeared that no one had ever heard my father’s simple peasant wisdom: never do something less than 100%, a slightly more practicable version of the professional athlete’s wisdom, which adds at least another 10% to the standard. Too many of my students complained about their grades despite seemingly putting very little effort into their studies, and my colleagues were barely better, complaining about a multitude of moderately effortful tasks, like grading, completing annual reports, attending meetings, and even preparing for class, all while also feeling violated for not being honoured by their Deans for performing the basic tasks appointed to them and for which they were relatively well paid. They all seemed unfamiliar with St. Pope John Paul II’s Laborem Exercens: “And yet, in spite of all this toil – perhaps, in a sense, because of it – work is a good thing for man.” I thought, how could anyone, at any time but especially today, think that what’s needed in school is more leisure? We need, instead, to work more, to be less leisurely about our studies.

I knew that leisure, skole in ancient Greek, meant something like the freedom to pursue properly human things, like the very philosophy I presumed to pursue in the academy. I knew that skole is the root of school both etymologically and conceptually, that school is leisure, even if we don’t realize it in both senses: being aware of and making real. I knew, in short, that leisure was a good, especially in schools. But intellectual cultivation takes a lot of effort, a lot of hard work. It just didn’t seem that whatever was wrong with the world – and there was and still is plenty – could be addressed by being leisurely. Now’s not the time for leisure.

If by “leisurely” we mean “lackadaisical”, then I wasn’t too off the mark, but as far as the need for leisure is concerned, I was wrong. It is definitely the time for leisure. There is time for work – lots of it. But there must also always be time left for freedom from work and freedom to leisure. If schools will be places of study, which is to say of contemplation of the highest things, they must be places of leisure. We do, thus, need more leisure not less. It is, in short, always the time for leisure.

Aristotle ends his Nicomachean Ethics with a defense of contemplation, the study of the things that exist eternally. Though a happy life requires virtuous character, which is the active comportment of a person’s life that produces good and beautiful actions, including political and economic ones, the summit of happiness is not practical; it is theoretical. The most complete human happiness requires, in addition to worldly action, the unadulterated and, practically speaking, useless apprehension of the highest things: the true, the good, and the beautiful.

Practical things are human, of course, and good humans do those things well. Nonetheless, the best and most serious humans also contemplate, and they do so for the sake of contemplation itself because it results in happiness: “happiness extends as far as contemplation does, and the more it belongs to any beings to contemplate, the more it belongs to them to be happy, not incidentally but as a result of contemplating, since this is worthwhile in itself” (1178b).

We need material wellbeing as a condition of living, but we need contemplation to live well. Humans are obviously material beings; thus, they need food, drink, clothing, shelter, medicine, and exercise, as well as the means to secure them. But external prosperity is insufficient for happiness because humans are more than just matter in motion; they are spiritual beings, too, and spiritual beings flourish through contemplation, by studying the eternal things, the divine things. It’s not just that contemplation is pleasant, promotes happiness, and might, accordingly, be a praiseworthy addition to material wellbeing. Aristotle goes further: “happiness would be some sort of contemplation” (1178b). Without it, man cannot be fully happy.

Serious people take the highest things seriously, and they consider mundane things, however needful they are, as less serious, if not altogether unserious. This is what Fr. James Schall called the unseriousness of human affairs. Many human things are good, but next to God they simply aren’t serious; indeed, they have worth because they are elevated by God. Some human things are less than unserious; they are harmful to our flourishing. As Schall puts it, “our lives have a certain importance, but only in the light of the seriousness of God” (xiii). Worship matters a lot, but so do philosophy and art, albeit less; food, politics, and economics matter, too, but even less so; the current cultural or ideological fads matter not at all.

The serious person wants to apprehend the permanent things. Such apprehension is proper to human nature; it is necessary for genuine human flourishing. Put differently, the most virtuous people take most seriously those things that don’t pay off, that have no economic, social, or political price. Serious people desire that which is intrinsically worthwhile, whether the pursuit of it is valued by others or not. They don’t disregard useful things, but they put them in their proper place, as instrumentally good, not as goods in themselves. What is useful may be worth pursuing, but it isn’t the substance of happiness. Contemplation isn’t useful; it is useless.

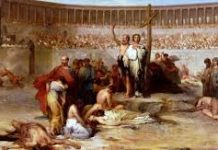

The happiest person loves and pursues the highest things for their own sake, not for any concrete benefit that might accrue from such pursuit. It is true that genuine study results in what nowadays we call “soft skills”, the realization of those natural dispositions that allow humans to speak well, reason validly, and make sound judgments. But these are not the goals of study. Indeed, it may even be the case – and I think it is – that the so-called soft skills are less likely to be developed properly in the student who is overly pragmatic about it. If all I want from study is the cleverness of soft skill, I will miss the grounding in truth that is needed for genuinely true speech, reasoning, and judgment. The person who studies for the sake of study itself is, for this reason, strange, as the workaday world values not the grounding but the pragmatism of intellectual skill, its cash value, so to speak. The highest pursuits can, thus, make one out of place. The workaday world values what can be measured, particularly monetarily. Those who value those things less, if at all, will be strange, even threatening to the order of the workaday. It is not that everyone who doesn’t fit in pursues the highest things, but those who do also don’t fit in – like Socrates, like the prophets, like St. John the Baptist, like the Apostles, like all martyrs, like, above all, Jesus Himself.

Aristotle observes that “contemplation seems to be the only activity loved for its own sake, for nothing comes from it beyond the contemplating;” for this reason, “happiness seems to be present in leisure, for we engage in unleisured pursuits in order that we may be at leisure” (1177b). Of course, we work, toil, and submit to the burdens of everyday life. It is properly human to work, and if being human is worthwhile, then it is good that we do so. Work is more than a necessity; it can be uplifting and salutary, as the honest toil of everyday life results in not just common and crude benefits, like money, but in fine things, like the means to support a family and help our neighbours. Even a professor like me knows the satisfaction of a hard day’s work, both for its results and, to some extent at least, for the pleasure of the activity itself. Work is distinctly human, as St. John Paul II notes in the opening of Laborem Exercens: “Work is one of the characteristics that distinguish man from the rest of creatures, whose activity for sustaining their lives cannot be called work. Only man is capable of work, and only man works, at the same time by work occupying his existence on earth.”

But, Aristotle says, we don’t work just for the concrete benefits to ourselves and others; the final goal of work isn’t the satisfaction of needs or of wants. We work, sometimes even to exhaustion, in the hope that a little time remains, a little bit of freedom from toil, from the burden of pursuing the necessities of life. We work to have leisure. The true goal of work is freedom from work. As Catholics we know, or should know at any rate, that Sunday is not just a day of rest, it is the culmination of the whole work week and of the burdens and toils of everyday life. It is the leisured freedom from work needed to worship God and, in so doing, to realize our humanity as created beings made in His image. It is the purpose and end of work.

We can squander that freedom, of course. We can spend it in more work – housework, yard work, and whatever myriad ways that we use our time to yield measurable results. We can also spend it doing nothing more than filling that time with amusements, activities that bring us immediate pleasure but do not elevate us beyond the immediacy of our material existence: television, cinema, internet, and social media may be among the most obvious examples, but clearly not the only ones, as humans have little trouble finding ways to entertain themselves. These are ways, in effect, to negate leisure, to evade the freedom that is the natural end of all our work.

Properly used, leisure is truly free; it is the time during which humans can attend to their very humanity for no other reason than that doing so is more true, good, and beautiful than not, and it is the activity by which they might become a little more true, good, and beautiful themselves. Leisure is contemplative, which also means that it is required for happiness. It is thus, indeed, always the right time to leisure.