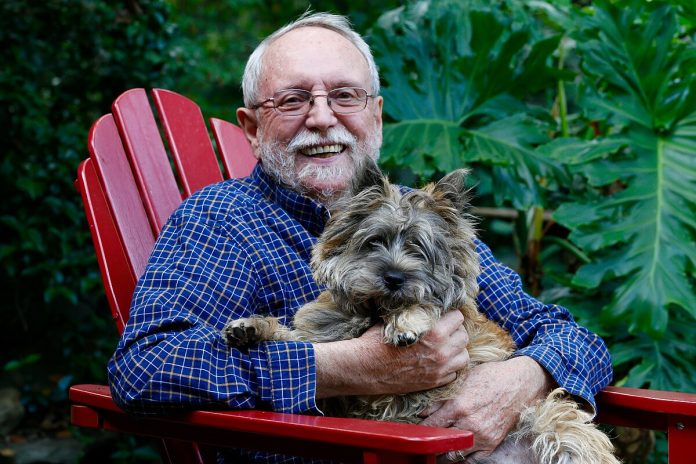

Philosopher Michael Ruse departed this world on November 1, 2024, at the age of 84. And although I had never met Michael, it is with sadness that I reflect on his passing. I had briefly corresponded with him a few years ago. I knew by listening to him in debates, interviews, and lectures over the years that he possessed a sharp wit, a keen sense of humour, as well as integrity.

In the fall of 2018, I had reached out to him to see if he would endorse my first book, On the Origin of Consciousness. Even though I knew he would ultimately disagree with my argumentation, I reckoned that if he did offer an endorsement or commentary, it would be worth the while, given his long history within the debate of evolution versus creation and the relationship between science and religion. In the end, he did not disappoint. His endorsement stated, “Sometimes you read a book where you disagree with just about everything the author claims—starting with the dedication! And yet… You learn and rethink. I feel exactly that way about Scott Ventureyra’s On the Origin of Consciousness. I intend that as high praise.” My only regret was not including his endorsement on the back cover, instead opting to include it solely in the first pages. Perhaps if I produce a second edition, I will place it on the back cover. Just to get a glimpse of his sense of humour, this was my dedication: “This book is dedicated to the God of all mercy and love; the co-Creators of all existence: God the Father, God the Son, and God the Holy Spirit.”

Several years after its original recording in 1996, the late conservative writer and Catholic William F. Buckley, Jr., hosted a debate that first introduced me to the thought of Michael. The debate pitted evolutionists, such as a protestant named Barry W. Lynn, a Catholic cell biologist named Kenneth R. Miller, and secular humanists like Michael himself and Eugene Scott, against Christians and proponents of intelligent design, including lawyer Phillip E. Johnson, biochemist Michael J. Behe, and another secular humanist and philosopher named David Berlinski. You can find the debate on YouTube under the title, “A Firing Line Debate: Resolved: That the Evolutionists Should Acknowledge Creation.” The debate sparked my interest in questions related to creation and evolution, and it led me to discover the works of most of the debaters. Over the years, I amassed a collection of books on the subject, including many of Michael’s.

Michael was a prolific author, gifted communicator, and top-notch philosopher of science, specializing in the philosophy of biology and the creation-evolution debate. His work shaped and influenced much of the critical discourse on evolution, creation, intelligent design, and ethics. Notably, Michael was a key expert witness in the 1981 Arkansas creation trial (McLean v. Arkansas Board of Education). Despite our significant differences, I recognize in him a colleague and mentor whose openness to dialogue bridged divides between worldviews often set in opposition. His life’s work has left an indelible mark on scholars and thinkers worldwide, and his legacy will undoubtedly continue to shape the conversation with respect to creation, intelligent design, and evolution for generations to come. Although he was a friendly critic of creationism and intelligent design, he was a staunch defender of academic freedom and freedom of speech. He would often engage in constructive conversations with creationists and proponents of intelligent design. Michael participated in some important works with intelligent design theorist, mathematician, and philosopher, William Dembski, such as Debating Design: From Darwin to DNA and Intelligent Design: William A. Dembski & Michael Ruse in Dialogue.

Even though I thought he was deeply mistaken in his embracing of Darwinism, I respected his thought and ability to relate complex issues in accessible ways to intelligent laypersons. I agreed with Michael on universal common descent but disagreed that the Darwinian model, whether in the traditional sense or in its modern synthesis (Neo-Darwinism), was sufficient to explain the diversity and organized complexity of life. In a forthcoming article, I explain what I perceive to be the bridge between evolution and intelligent design and how the term “evolution” has been unjustly hijacked by scientific materialists for well over a century.

The first work by Michael that I read was Can a Darwinian Be a Christian? (Even though the first book I bought of his (having no clue who he was) upon starting my studies in philosophy and theology and curiously skimming through it at the University of Saint Paul’s bookstore was Taking Darwinism Seriously.) In Can a Darwinian Be a Christian, he directly addressed the issues that have bedevilled scholars and religious thinkers for more than a century. He did not offer simplistic answers; rather, he sought a “middle ground,” exploring the ways in which evolutionary theory and Christian faith might coexist without compromising their distinct frameworks. The work tackles all kinds of issues, including the soul, miracles, socio-biology (social Darwinism), the problem of evil, and even the religious significance of the potential existence of aliens. Unlike many in his field, he was never hostile to religion while also upholding the integrity of science, as he understood it. He occupied a rare space, striving to understand how each side could contribute to a fuller understanding of reality. This book showed me that there was no logical incompatibility between being a Christian and a Darwinist. As a non-believer, he wrote sympathetically and charitably about Christian belief; his Quaker upbringing likely played a significant role in his non-combative approach to dialogue with believers. Nevertheless, after many years of intense research and thought, I came to reject full-blown Neo-Darwinism based on the scientific evidence, not because it posed a threat to my Catholicism.

For myself, as a Catholic philosopher and theologian who specializes in the science and theology interaction, Michael’s approach and openness always served as a reminder that the boundaries between faith and science are not as rigid as they may seem. Michael’s balanced stance challenged the view that science and religion are inherently at odds; he instead demonstrated that they could exist in constructive dialogue. His intellectual honesty and courage in questioning assumptions, whether scientific or theological, defending unpopular positions, and most importantly, his openness, served as inspiration for my own work.

Michael was a thinker unafraid to criticize both atheists and believers. In recent years, as a response to the New Atheists, he wrote a book for Oxford University Press titled Atheism: What Everyone Needs to Know. He also publicly disavowed and admitted his embarrassment of the New Atheists’ aggressive rhetoric and unnuanced criticisms, which diminished understanding of religion’s role in human experience (regardless of one’s beliefs). In 2018, he stated the following about Richard Dawkins’s unsophisticated view of Christian philosophy:

Partly it is aesthetic. They are so vulgar.

Dawkins in The God Delusion would fail any introductory philosophy or religion course. To take one example, the Ontological Argument for God was first devised by Anselm and refurbished by Descartes. Roughly, it runs thus: God is by definition that than which none greater can be thought. Does He exist? Suppose He doesn’t. Then there is a greater who does exist. Contradiction! Hence, God exists.

In The God Delusion, Richard Dawkins dismisses this longstanding and much debated philosophical argument with a few sneering paragraphs. His critique is on a par with someone arguing against Dawkins’ own body of work by saying that selfish genes cannot exist because genes cannot be selfish (and with about as much understanding or sensitivity). But hardly any serious theologian or philosopher thinks the Ontological Argument is valid in the way I have just described it. It has been reframed and reworked. Every serious theologian and philosopher knows that the argument leads us into important and sophisticated questions about the nature of existence. Does the notion of necessary existence—which must surely be true of God if he exists—even make sense? And so forth. To arrogantly dismiss the argument is bad scholarship and, worse still, bad taste. Ironically, I get on better with many of my Christian interlocutors than I do with many atheists.

Michael argued that while science addresses physical reality, it is not fully equipped to answer the existential questions that lie at the heart of religion. He argued that belief systems serve essential functions by providing meaning, values, and moral structure. Interestingly, he was candid enough to explore the question of how Darwinism even became a religion for many of his colleagues and early defenders:

Evolution is promoted by its practitioners as more than mere science. Evolution is promulgated as an ideology, a secular religion—a full-fledged alternative to Christianity with meaning and morality. I am an ardent evolutionist and an ex-Christian, but I must admit that in this one complaint—and [Dr.] Gish [a proponent of Scientific Creationism] is but one of many to make it—the literalists are absolutely right. Evolution is a religion. This was true of evolution in the beginning, and it is true of evolution still today.

It’s important to note that many have misinterpreted this quote or used it for their own purposes over the years, but he does not imply that Darwinism is not a legitimate scientific theory or that adhering to it requires atheism; rather, he suggests that many have adapted it to explain the big questions of life.

Engaging with Michael’s work—whether in agreement or often in debate—has pushed and deepened my own viewpoints throughout the years. His honesty as a scholar and thinker is on full display in his capacity to be respectful of other perspectives while firmly defending his own convictions. He demonstrated the potential for civil and fruitful discourse between individuals of many differing beliefs. To me, he was more than simply a philosopher of science, professor, or public intellectual; he was a determined bridge-builder who encouraged people of all backgrounds to examine the assumptions underlying their most deeply held beliefs and values. Although, sadly, the world has lost a humble yet brilliant mind, his many writings will endure and precipitate enduring conversations on life, morality, and the nature of belief. In a world wrought by so much division based on not only religion but also political and philosophical ideologies, his legacy serves as an example of how to foster dialogue and understanding in the face of not only disagreement but often misplaced anger and hatred.